Everyone knows that it takes two to tango, but no one can agree on the origin of the dance. For 150 years its characteristic Latin rhythm has been shaped and adapted to nearly every Spanish-speaking national culture.

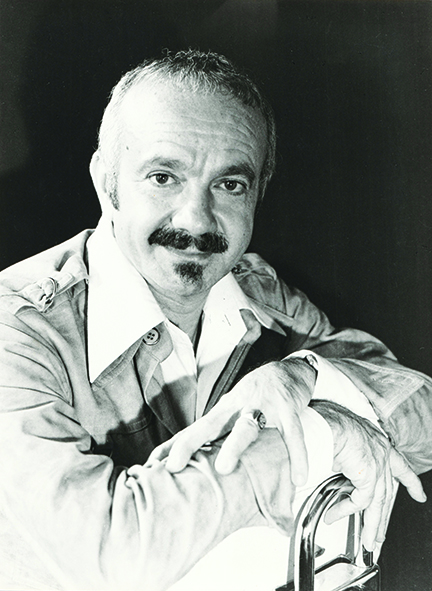

The arrabal, the squalid immigrant slum of the late nineteenth century outside Buenos Aires, bred its own version of the tango. A popular song, laced with bitter urban protest, had by the 1930s developed into a pessimistic expression of a fatalistic, melodramatic outlook on love and life. It was into this world that the parents of Astor Piazzolla arrived from Italy. And it was the music of the arrabal that shaped Piazzolla’s entire career.

During the Depression, Piazzolla’s family moved to New York, where he learned piano and the bandoneón, a type of concertina with 38 notes that had become the predominant instrument in the tango ensembles of Argentina. After a sojourn in Paris, studying composition with no less an eminence that Nadia Boulanger, Piazzolla returned to Argentina to form his first Tango Octet and later his renowned Tango Quintet, featuring bandoneón, violin, piano, electric guitar and bass.

Influenced by his studies in Paris and by classical forms, Piazzolla developed a unique style that he called the “nuevo tango” (new tango) and a cut above the traditional tangos. No longer dance music, Piazzolla’s tango became concert music, although for the nightclub rather than the concert hall.

Written as four distinct works between 1964-1970, Cuatro estaciones were not originally intended to be performed as a suite, although in later years Piazzolla occasionally put them together to perform with his quintet. They were originally scored for violin, electric guitar, piano, bass, and bandoneón but have been transcribed for many instruments and instrument combinations. Finally, in the late 1990's, Russian composer Leonid Desyatnikov arranged all four seasons for string orchestra and solo violin.

While Piazzolla occasionally quotes Vivaldi (in “Summer” and especially in “Winter”) Buenos Aires’s climate is mild without the drastic seasonal fluctuations of Venice. The four movements of Piazzolla’s suite describe the vagaries of human emotions rather than the weather.

Each of Piazzolla’s Seasons is a single movement tango, although they all loosely follow an internal fast-slow-fast tempo pattern recalling the tempi of the Vivaldi’s three movement concerti. Likewise, Piazzolla’s work features a violin soloist, although there are some extensive solos for the other instruments as well. In the improvisatory spirit of Piazzolla’s original band, soloists sometimes add their own cadenzas. Listeners can also expect to hear some scrapes, squeaks, snaps and grunts that would have made poor Vivaldi blanch.

"Verano porteño" (summer) sports a guttural main theme with a double-stopped dissonant glissando. The first part of the theme is repeated in several subtle variations. A little riff from Vivaldi blends into a slower more lyrical middle section. Note, however, that underlying each theme is an ostinato tango rhythm accompaniment.

"Otoño porteño" is a tango with two internal cadenzas. It opens with an ostinato suggesting jazzed up cicadas, leading into the first of the movement's two themes. After a few varied iterations of the theme comes a real surprise, a long solo for cello lasting almost two full minutes of the seven-minute movement. The first part, a cadenza, is reminiscent of Bach's unaccompanied cello suites; the second part of the solo introduces the slow middle section of the movement. A return to a variant of the first theme leads into a new cadenza, this time for the violin, plus varied reprise of the slow cello theme. A coda of a snarling string snapping and harshly bowed variation of the opening theme concludes the movement.

"Invierno porteño" sports a sultry theme that the composer repeats in different tempi and moods. A second theme grows out of the main theme but is definitely subsidiary to it. A quote from Vivaldi's "Winter" surreptitiously inserts itself into the violin part later in the movement. There are two cadenzas, and it concludes with a coda in the style of Vivaldi, although it is not a direct quote.

Piazzolla’s final season, "Primavera porteña," once again has a Baroque flavor– although more in the style of Bach than Vivaldi. The solo violin begins with a theme, plus scratchy rhythmic additions, that is eventually joined by the solo cello in a contrapuntal duet before the movement takes off with the customarily rhythmic full orchestra accompaniment. In line with the style of the entire set, a slow theme comprises the middle section of the movement. Note how Piazzolla patterns the pizzicato texture of the slow section to Vivaldi's style (here from "Winter") without actually quoting it.