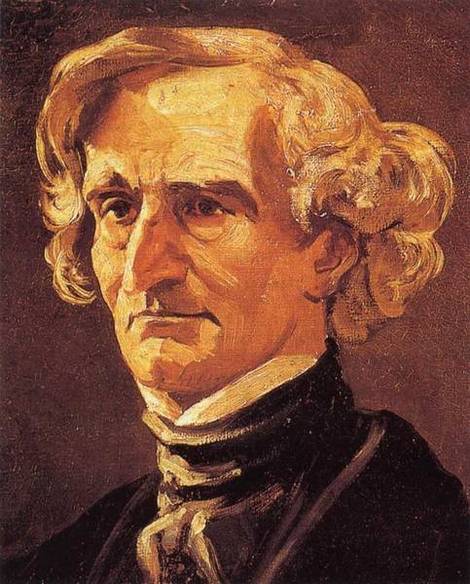

Hector Berlioz

Roman Carnival Overture (1844)

Hector Berlioz (1803-69), was a French composer of the Romantic period. His father, a physician, sent him to Paris to study medicine, but young Berlioz was more interested in the Paris-Opéra and applied himself so well to the study of music that he was accepted into the Paris Conservatoire. Not much later he won the prestigious “Prix de Rome,” which paid for his staying two years in the Eternal City where he might continue his composition.

Berlioz felt stifled in the Villa Medici (his love-life at the time was quite active but based in Paris), so he was happy to return to Paris after two years and married the famous Shakespearian actress Harriet Smithson. The two lived in the house painted by French painter Maurice Utrillo numerous times and was a gathering place for many artists of the time, including Chopin.

At the time, Berlioz was enchanted with the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, a rakish Italian sculptor, and determined to create an opera based on the artist’s life. As was sadly typical of Berlioz’s works, the opera was not well received by the Paris audiences though many critics have stated that the work is a masterpiece.

But then, like many other composers, Berlioz “repurposed” music from his unpopular opera, and thus was the birth of the “Roman Carnival” overture. In his 1844 work, Berlioz took themes from his opera and set them in a rollicking nine-minute tone poem. The first, lovely melody of the overture, set for the English horn, recalls Cellini’s aria in praise of his beloved. What follows is a relatively wild folk dance in triple time. The first, plaintive theme recurs later in the overture when it merges with the frenetic dance before the overture whirls away in the dramatic alchemy of orchestral forces—instrumentation being perhaps Berlioz’s greatest musical gift. Significantly, Berlioz had published a study of the use and function of orchestra instruments, the 1844 Treatise on Orchestration, which provided composers of the time—and to this day—an invaluable guide to their work.

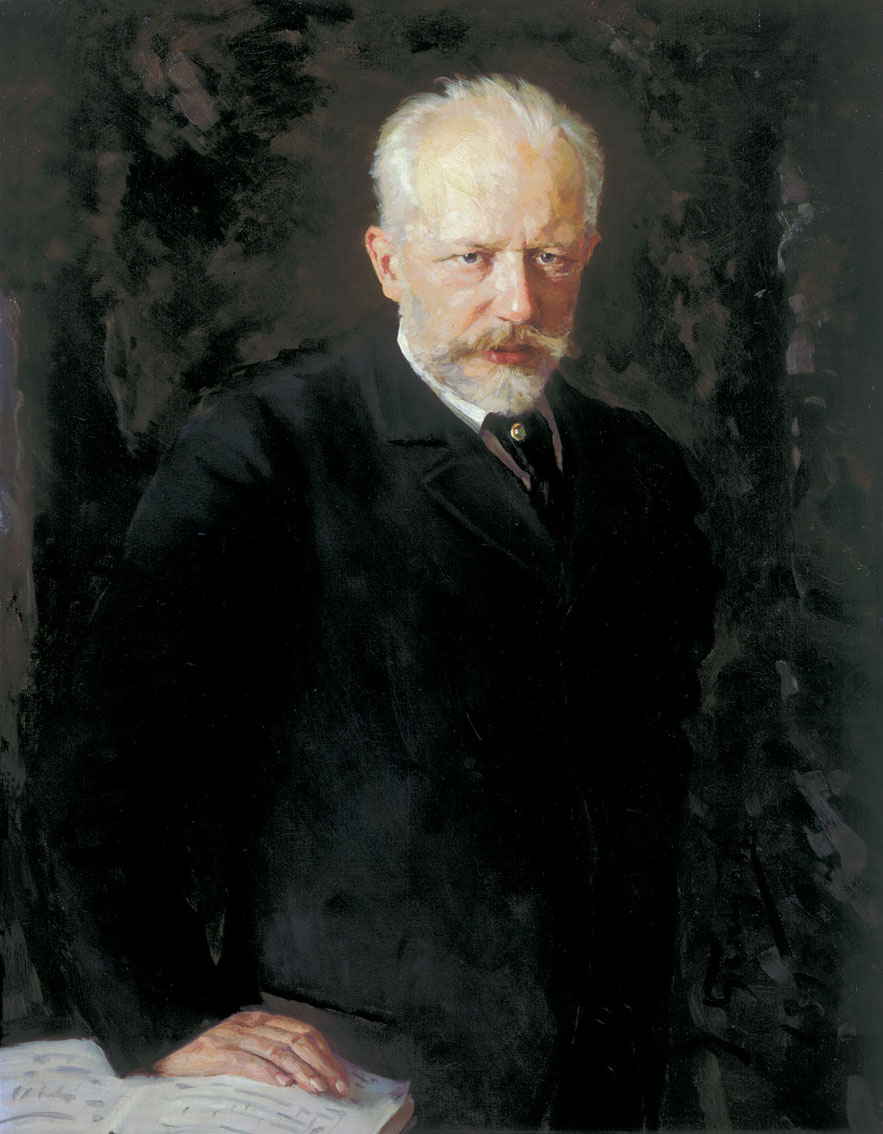

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor (1874)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-93) is still revered as perhaps the greatest of Russian composers. Despite his relatively short life, he left behind a large collection of compositions in just about all genres—symphonies, operas, ballets, concertos for piano and violin, cantatas, string quartets, as well as a host of smaller works for piano and voice.

After the great public success in 1869 of the ballet Romeo and Juliet, Tchaikovsky quickly completed an opera and a symphony before turning to the creation of his first piano concerto. He gave the score, completed in 1874, to his friend Nikolay Rubinstein, head of the Moscow Conservatory and scion of a great musical family. Rubinstein savaged the young composer’s work, pronouncing it “unplayable” and badly written. Fortunately, Tchaikovsky made few significant changes to his new work though he revised the work several times in later years. Instead, Tchaikovsky found in conductor and pianist Hans von Bülow a champion of the concerto and one who had the requisite technique to perform the warhorse work as well. The premiere took place in 1875 in Boston to great public acclaim. Russia had to wait another six months to hear what would become one of music literature’s most well-known works. It has become a standard of concert repertoire ever since then.

The first movement of the concerto in particular has become synonymous with the fiery passion of romantic music. Though the piece begins in B-flat minor, the piano enters with thundering chords in D-flat major that bounce down the keyboard. The grand initial motif recurs towards the end of the movement. The second movement opens with a slow flute solo. The piano enters repeating the lovely theme then runs off in a contrasting presto section before returning to the calm of the original theme. The third movement makes use of a jaunty Ukrainian folk melody with lively dotted rhythms. Treacherous descending double octaves in the piano part announce the triumphant end of the concerto, which returns to the upbeat key of B-flat major. For a time the concerto served as unofficial anthem of the Russian Olympic Committee (when because of a doping scandal the Russians could not use their traditional national anthem).

But much of the fame of this music in the United States comes thanks to the musical prowess of Harvey Lavan (Van) Cliburn, the lanky Texan pianist who won the top prize in the first International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in 1958—as well as the hearts of most Russians in attendance. It was of course the height of the Cold War, but the skillful, sensitive playing of the young Texan warmed the listeners in the concert hall considerably; it was the beginning of a true cultural exchange. In the competition Cliburn also played Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in D-minor, as if the thorny technical requirements of Tchaikovsky’s work were not enough and he had to display the musical electricity of the more contemporary Russian composer as well. In his celebratory solo public performance in Moscow, Cliburn showed himself to be a real crowd pleaser. As an encore he offered up his own rendering of the popular Russian song Moscow Nights. He even gave a small speech in Russian, demonstrating for at least a time that art may trump politics and political animosity. For a time this great music became a lingua franca for the two nations. The 1958 recording of this concerto made Van Cliburn a household name in the US and became the first classical recording to go platinum.

Valerie Coleman

Seven O’Clock Shout (2021)

Valerie Coleman (b. 1970) spent her youth in Louisville, Kentucky. Her musical aptitude showed itself early in life, and by the age of 14 she had written three full-length symphonies. While in high school she played flute, won a number of music competitions, then studied flute performance and composition at Boston University. From there she did master’s work at Mannes College of Music in New York City. In the late 90s, she formed a chamber music ensemble, the Imani Winds (‘Imani’ means ‘faith’ in Swahili). The group garnered a number of awards in its lifetime, among them the 2001 Concert

Artists Guild competition, and their 2010 recording Terra incognita was named one of the best American Contemporary Classical Albums of that year.

Coleman works as both performer and composer. She has performed in venues around the country, and her compositions can regularly be heard on NPR and other national broadcasting stations. The Washington Post has recently put Coleman on its list of “Top 35 Women Composers,” and Performance Today named her 2020 Classical Woman of the Year.

Tonight’s work was commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra in the midst of the Covid pandemic. In this jubilant work, Coleman celebrates the hard work and unstinting bravery of essential workers. The piece begins with a trumpet fanfare that heralds the efforts of these brave women and men. The musical texture thickens, the tempo builds. It is seven o’clock, the shift changes at work, and the workers shout out their relief. A trombone makes a joyful, solo rallying call; it is answered by the other instruments.

For the essential workers and perhaps for all of us, the years of the pandemic have been full of illness, frustration, even hopelessness for some. In describing her purpose in creating this work, Coleman has said that music can “put us on the front lines of healing.” This composition, what she has termed a “declaration of survival,” is testimony to that sentiment.

Ottorino Respighi

Pines of Rome (1924)

Nationalistic Italian composer Respighi was born in Bologna in 1879 and died in Rome in 1936. Raised in a musical family, he garnered advanced degrees in both violin performance and composition, furthered his composition instruction with visits to Rimsky-Korsakov in St. Petersburg, and later worked with Max Bruch in Germany.

Pines of Rome was written as part of a now-famous trilogy of tone-poems that contain some of Respighi’s most enduring music, including the Fountains of Rome (1914-16) and Roman Festivals (1929). In the Fountains of Rome the composer strove to provide his musical impressions

of the natural beauty of those human-made features of the Roman landscape. By contrast the composer writes that Pines of Rome serves to remind listeners of the glorious sites and moments of the Roman past.

Pines of Rome is divided into four sections played without interruption. The first movement, “The Pines of Villa Borghese,” depicts children as they play and sing on these lovely grounds. The second movement is much more somber, which is suggested by its title, “Pines near a catacomb.” In “The Pines of the Janiculum” Respighi creates an evening scene with the majestic trees (also known as “Umbrella trees” because of their urn-like shape) standing stalwart tall against a darkening sky; birdsong can be heard. The final movement builds dramatically to a martial conclusion: you can hear the Roman army marching as it approaches the city. This is the Appian Way, a roadway built by the Romans, flanked by pines.

Not surprisingly, Respighi and his wife called their home in Rome “The Pines.” A year after their arrival at the villa in 1921, Mussolini came to power; he was to become a great fan of Respighi and supporter of his music. In the course of his musical career Respighi collaborated with the ultra-nationalistic (some would say “fascist”) writer Gabriel D’Annunzio. The composer’s reputation in Italy suffered from this “guilt by association” until quite recently. Yet events of the composer’s life show his devotion to art, not politics.

- Podcast

- Conductor Biographies

- Bill Hemminger Biography

- Photos

- Videos

- Articles and Reviews

- Radio Broadcast Schedule

- History of the EPO

- Mission and Values

- Board of Directors 2025-2026

- Sponsors 2025-2026

- Philharmonic Gives Back

- Donors 12/1/2024 - 12/1/2025

- Thoughtful Tributes 12/1/2024 - 12/1/2025

- Past Events