Arthur Miller, born on October 17, 1915, in New York City to Jewish parents of immigrant descent, was one of America's most influential playwrights of the 20th century. Miller's exposure as a Jewish man to antisemitism and fascism, as Hitlerism and the Holocaust consumed Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, and his upbringing in America during the Great Depression, which led to his family's financial struggles, profoundly influenced his perspective and writing into his adulthood. Like Ibsen, his works are celebrated for their profound exploration of social issues and the complexities of human nature. Among his most acclaimed plays are All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953), and A View from the Bridge (1955).

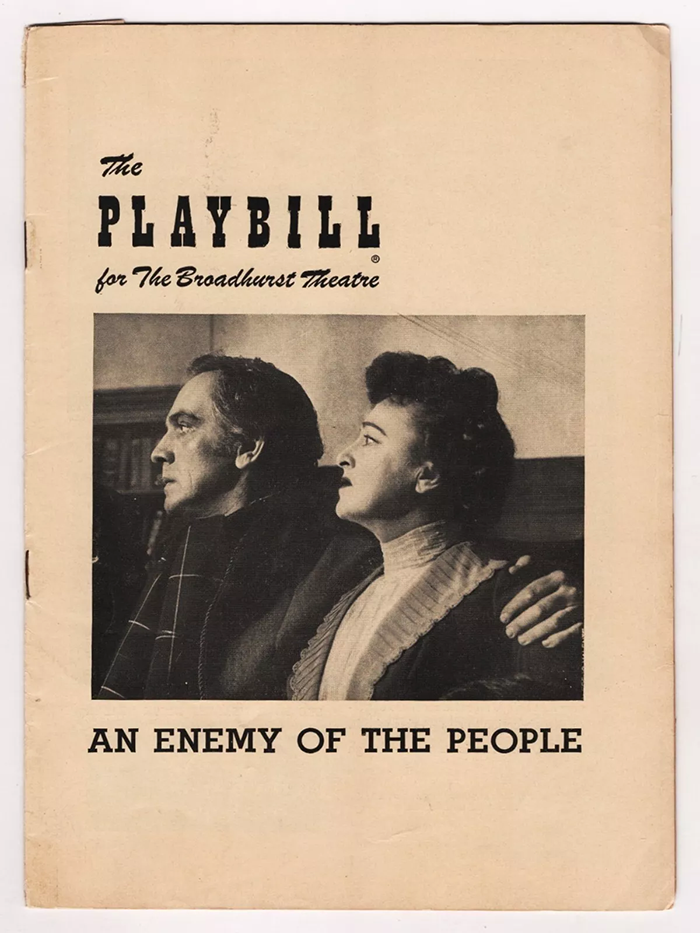

The only play Miller ever adapted was his "initial response to the Communist witch-hunts that began in the early 1950s", Henry Ibsen's An Enemy of the People. In 1947, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) began to hold hearings on Communist activity in Hollywood led by Senator Joseph McCarthy during what was called the Red Scare. Two years later, mainstream actors and friends of Miller, Frederic March and his wife Florence Eldridge, were named in Coplon v. United States, a case during the Red Scare when Judith Coplon, a woman who worked in the U.S. Department of Justice, was accused of spying for the Soviet Union. Suspected of being communists, Frederic March and his wife Florence Eldridge began to lose work; therefore, "in response, they decided to stage Ibsen's play An Enemy of the People, in which they saw the lead characters' situation as resembling their own: All are accused by a mob hysteria that views them as a threat to the well-being of the larger society." Robert Lewis, a director from the Group Theatre, was approached first, and after he and March asked Miller to adapt the work—despite Miller having never read the Ibsen piece before their request—he agreed after reading it.

Miller stated, "I decided to work on An Enemy of the People because I had a private wish to demonstrate that Ibsen is really pertinent today, and that he is not 'old-fashioned." His perspective as a Jewish writer—especially in the post-Holocaust era—likely shaped his interpretation of the play's themes. He saw fascism rising in the United States and was shocked that "the outrageous had so suddenly become the accepted norm." While Miller stated at the time his revival was first staged that anti-Communist themes resonated with audiences even without directly being addressed, the theme of environmental dangers was still prevalent. The themes of the struggle between truth and the majority, as well as the risks of environmental pollution, were relevant in the 1880s and the 1950s and remain significant today.

While Miller never stated directly that he was a communist, he was very clear in his writing and public speaking that he was liberal-minded. As a young man, however, he stated that "...Marxism was the hope of mankind and of the survival of reason itself," and he attended many Communist Party meetings. Six years after his adaptation of An Enemy of the People debuted on Broadway, "Arthur Miller received his subpoena to testify before HUAC on 8 June 1956." During this hearing, he invoked "...the First Amendment's right to free speech, and thus the right to silence." Miller requested that the committee allow him to disclose his political beliefs, affairs, and actions but refrain from asking him questions regarding others. While this public confrontation with the HUAC damaged Miller's reputation to some extent, especially among more conservative circles, his eventual success showed that while his career may have been impacted by the political pressures of the time, he managed to continue contributing powerfully to American theater.

“Ibsen’s Warning”, Arthur Miller (1989)

“It is a terrible thing to have to say, but the story of Enemy is far more applicable to our nature-despoiling societies than to even turn-of-the-century capitalism, untrammeled and raw as Ibsen knew it to be. The churning up of pristine forests, valleys and fields for minerals and the rights of way of the expanding rail systems is child’s play compared to some of our vast depredations, our atomic contamination and oil spills, to say nothing of the tainting of our food supply by carcinogenic chemicals.

It must be remembered, however, that for Ibsen the poisoning of the public water supply by mendacious and greedy interests was only the occasion of An Enemy of the People and is not, strictly speaking, its theme. That, of course, concerns the crushing of the dissenting spirit by the majority, and the right and obligation of such a spirit to exist at all. That he thought to link this moral struggle with the preservation of nature is perhaps not accidental. After all, he may well have found enough examples of moral cowardice and selfish antisocial behavior in other areas such as business, science, the ministry, the arts or where you will.

I am sure that few in the first New York audience of the early Fifties were terribly convinced by the play’s warnings of danger to the environment. The anticommunist gale was blowing hard and it was the metaphor that stood in the foreground; moreover, in that time of blind belief in rational, responsible science, any suggestion that, for example, we might be building atomic generating plants that were actually unsafe would have simply been dismissed as dangerous obscurantist nonsense.”

Excerpt from Arthur Miller’s testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee)

“Mr. Miller: Mr. Chairman, I understand the philosophy behind this question and I want you to understand mine. When I say this I want you to understand that I am not protecting the Communists or the Communist Party. I am trying to and I will protect my sense of myself. I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him. These were writers, poets, as far as I could see, and the life of a writer, despite what it sometimes seems, is pretty tough. I wouldn’t make it any tougher for anybody. I ask you not to ask me that question. (Miller confers with his lawyer) I will tell you anything about myself, as I have.

Mr. Arens: These were Communist Party meetings; were they not?

Mr. Miller: I will be perfectly frank with you in anything relating to my activities. I take the responsibility for everything I have ever done, but I cannot take responsibility for another human being.”