Welcome to the Bellingham Symphony Orchestra’s 46th Season. I am very excited to be serving as the President of the Board during this time, as we return to making music in person at the beautiful Mount Baker Theatre. Playing in the orchestra remains a joy for me as well as serving on the Board of Directors.

While the global pandemic presented many challenges, the resilience and creativity of our musicians, staff, and Board have allowed us to safely move forward this season and resume live performances. The support that we have received from our community during this time made it possible for us to present performances remotely last season, and your ongoing support allows us to continue presenting live performances. Thank you so very much.

We still have a long way to go to get back to pre-pandemic levels of performances and attendance, and I hope we can count on your continued support. Your gift at any level will make a significant impact on our ability to continue to move forward with our plans for the remainder of this season, and to perform for you music that is powerful, beautiful, and inspiring.

Ken Bronstein

President, Bellingham Symphony Orchestra Board of Directors

- Chopin composed his First Piano Concerto as a showpiece for himself, and gave the premiere at a farewell concert in Warsaw before moving to Paris.

- The Concerto’s finale is in the style a Krakowiak, a popular national dance in Poland during Chopin’s time.

- Brahms wrote his Fourth Symphony over two summers spent vacationing in the Styrian Alps.

- The finale of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony is a passacaglia, in which a constantly recurring theme is subject to no fewer than 32 variations.

PROGRAM NOTES

Though Ludwig van Beethoven died in 1827, his shadow continued to loom over subsequent composers until well into the twentieth century. In the realms of the symphony and string quartet—genres in which Beethoven demonstrated an almost superhuman command—any new attempt invariably invited unforgiving comparison with the great master. And even after the earned successes of symphonies by Schubert, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Schumann, and others, the widely held view among critics—and many composers as well—was nonetheless that Beethoven’s symphonic achievements could never be matched, let alone exceeded.

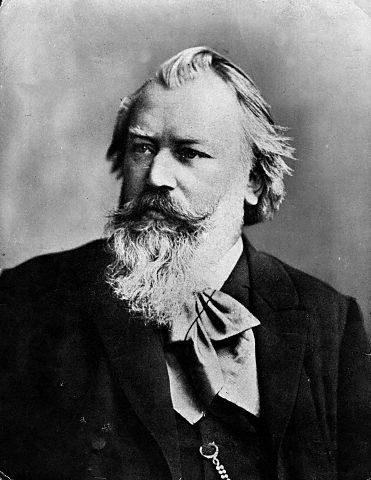

Of all the Romantic composers, perhaps no one was more sensitive to this attitude than Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Born six years after Beethoven’s passing, Brahms began work on a D minor symphony as early as 1854, upon hearing the elder composer’s legendary Ninth (also in D minor) for the first time. After completing nearly three quarters of the piece, he lost confidence in the work’s merits as a symphony, and repurposed two of the movements in his First Piano Concerto. The third found its way into Brahms’ German Requiem many years later.

Despite encouragement from his publisher, as well as from friends Robert and Clara Schumann, Brahms set his symphonic aspirations aside for nearly two decades. “I shall never write a symphony!” he told Hermann Levi in 1872. “You can’t have any idea what it’s like to hear such a giant marching behind you.” Instead, Brahms focused his attention on “secondary” genres with which he could distance himself from Beethoven’s legacy. Through the composition of serenades, chamber music, choral works, concertos, and the like, Brahms felt able to hone his craft while avoiding the harsh (and primarily self-inflicted) criticism he would have received in response to a symphony or string quartet.

But the elephant in the room was unavoidable, and in 1876 Brahms finally unveiled the first of his four symphonies to the world. The public response was glowing, and cleared the way for his final three installments to come in relatively quick succession: the sun-drenched Second in 1877, the rhapsodic Third in 1883, and finally the steely Fourth in 1885. Brahms composed the piece over the course of two summers spent vacationing in the alpine village of Mürzzuschlag in southern Austria. The piece is remarkably integrated and organic despite its long gestation. Its opening Allegro non troppo commences straight away with a sighing gesture in the strings that becomes the germ for nearly all the music that follows, including vigorous fanfares that remind us of the life and vitality contained in the otherwise darkly hued movement. Beginning with an ominous horn call, the expansive second movement unfolds into a wide-ranging fantasia that is by turns lyrical and defiant. The third movement is a rarity in Brahms: a true, unapologetic, full-throated scherzo bordering on the wildness of Berlioz, and complete with chiming triangle, piping piccolo, and growling contrabassoon. Before the Fourth Symphony’s premiere, the composer circulated copies of the score to a number of trusted friends, all of whom criticized the scherzo as being out of step with the rest of the piece. However, Brahms held to his convictions and retained the movement. Posterity has proven his choice to be the right one; the third movement’s joviality provides the perfect counterbalance to the seriousness of the rest of the symphony.

The finale is as terse and craggy as the scherzo is impetuous. Borrowing an eight-note theme from Bach’s cantata Nach Dir, Herr, verlanget mich (“I long to be near you, Lord”), Brahms turns to a Renaissance form,nthe passacaglia, in which a constantly repeating subject is passed around the orchestra: as a melody, or a bass line, or tucked away secretly among the inner voices. The structural restrictions of the passacaglia prove no barrier to Brahms, as he spins out no fewer than 32 variations of astonishing variety before bringing the symphony to an abrupt, yet decisive full stop.

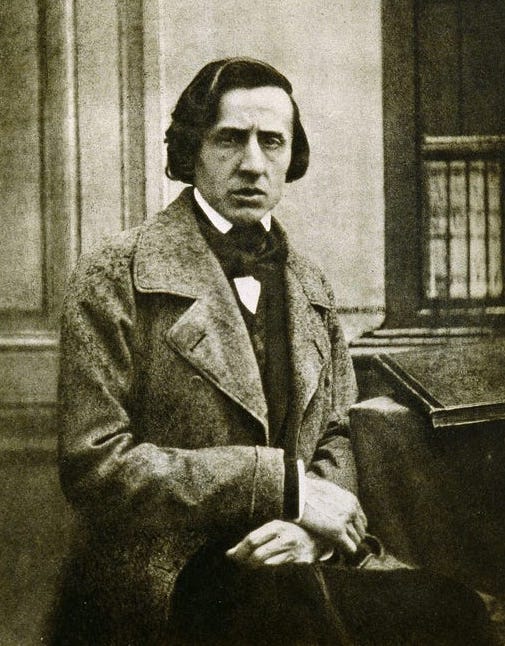

That Brahms could repurpose his early symphonic efforts into a piano concerto is indicative of his overall aesthetic philosophy: music first, forces second. The exact opposite could be said of his Polish predecessor Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) and his two piano concertos. These works are pianistic tours de force, a literal catalog of their composer’s advanced techniques, and untranslatable to any other medium.

Chopin spent nearly half of his life as an expatriate in Paris, where he was the exotic darling of the most rarefied social circles, demonstrating his singular virtuosity in private salon concerts and teaching piano lessons to the city’s elite class. While at first blush this life may read as frivolous, Chopin’s compositions—like his playing—are anything but. He was an artist of the highest caliber, and used his nearly inhuman technical facility to express musical ideas that were inaccessible to lesser pianists.

Much of Chopin’s most celebrated music comes from this time in Paris, but the pair of piano concertos date from his early years in Poland. In contrast with his Hungarian counterpart Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Chopin had little interest in composing for orchestra; the piano was his language and his life. He wrote his concertos as showpieces for himself, as was the expectation for virtuosos of his day. Consequently, the orchestral accompaniments to these pieces are exactly that: accompaniments. Critics have often lambasted Chopin for his orchestration, comparing him unfavorably to figures like Beethoven and Mozart, who tend to treat the orchestra as an equal conversational partner with the soloist. But in light of Chopin’s priorities—placing the soloist center-stage at nearly all times—his orchestral tailoring reveals an inimitable sensitivity and reserve. Never is the piano overshadowed, but rather supported and colored by the orchestra throughout.

Chopin’s concertos are numbered by publication rather than date of composition; the First Concerto was actually written immediately on the heels of his Second Concerto, and performed in a series of farewell concerts in Warsaw in 1830 before the 20-year-old composer made his westward journey to Paris. Its expansive first movement—with three main themes rather than the typical two—occupies nearly half of the piece’s duration. The central Romanze is disarmingly simple, anticipating Chopin’s later nocturnes. “It is not meant to create a powerful effect,” the composer wrote, “it is rather a Romance, calm and melancholy, giving the impression of someone looking gently towards a spot that calls to mind a thousand happy memories. It is a kind of reverie in the moonlight on a beautiful spring evening.” The brisk finale is set in the manner of a Krakowiak, a popular national dance of the time. Though he never returned to his homeland, this type of Polish influence would surface in Chopin’s music time and time again—most notably in his many mazurkas and polonaises—for the remainder of his life.

Copyright © 2022 Ryan Dudenbostel

Ryan Dudenbostel is the Director of Orchestral Studies at Western Washington University, where he conducts the WWU Symphony Orchestra, coordinates the graduate program, and directs the contemporary music ensemble NowHearThis! Previously, he was Music Director of the El-Sistema-based Santa Monica Youth Orchestra in Los Angeles. He recently served as Interim Artistic Director of the Marrowstone Music Festival, and regularly returns to LA for concerts with the Jacaranda new music series.

![]()

Program notes sponsored by: Garland Richmond & Richard Stattelman

We are so grateful for our generous sponsors!

Season: Peoples Bank & Bellingham Porsche/Audi

Concert: Exxel Pacific

Guest Artist: Louis Auto & Residential Glass

For a full list of BSO's sponsors, please visit our website sponsor page.

Musicians performing in this concert are in bold.

Music Director

Yaniv Attar (bio)

The Jack & Marybeth Campbell Music Director

Violin I

Dawn Posey (bio)

The Garland Richmond & Richard Stattelman Concertmaster

Shu-Hsin Ko

Acting Concertmaster (Assistant Concertmaster)

Heather Ray

Acting Assistant Concertmaster

Emily Bailey

Laura Barnes

David Bean

Gaye Davis

Joanne Donnellan

Irene Fadden

Matt Gudakov

Madeline Massey

Yelena Nelson

Sandra Payton

Krissy Snyder

John Tilley

Karen Visser

Bill Watts

Violin II

Yuko Watanabe

The Debbie & Steve Adelstein Principal 2nd Violin

Heather Ray

Assistant Principal 2nd Violin

Tara Kaiyala Weaver

Acting Assistant Principal 2nd Violin

Linnea Arntson

Liza Beshara

Judy Diamond

Kathy Diaz

Geneva Faulkner

Yoshimi Lin §

Ben Morgan

Lenelle Morse

Audrey Negro

Cecile Pendleton

Carla Rutschman

Joy Westermann

Viola

Morgan Schwab

The Byron & Becky Elmendorf Principal Viola

Eric Kean §

Acting Principal Viola

Katrina Whitman §

Acting Assistant Principal Viola

Virginia Arthur §

Kacey Bradt

Jo Anne Dudley

Alia Kerr §

Natalie Louia

Valerie McWhorter

Michael Neville

Jim Quist

Corey Welch

Cello

Nick Strobel

The Phyllis Allport Principal Cello

Samantha Sinai

Acting Principal Cello

Tallie Jones

The John W. Tilley Jr. Assistant Principal Cello

Brian Coyne

Acting Assistant Principal Cello

Erin Esses Lusk

Noel Evans

Omar Firestone

Jeremy Heaven

Cori Holquinn §

Rebekah Hood-Sava

Barb Hunter

Coral Marchant

Mary Passmore

Bette Ann Schwede

Daniel Watterson

Bass

Mark Tomko

The Charli Daniels Principal Bass

Eirik Haugbro

Assistant Principal Bass

Faye Hong

Anna Jull

Amiko Mantha

Ramon Salumbides §

Flute

Deborah Arthur

The Marcela Berg & Michael Addison Principal Flute

Gena Mikkelsen

Assistant Principal Flute

Piccolo

Gena Mikkelsen

The Carol & Dennis Comeau Piccolo

Oboe

Kristen Fairbank

Co-Principal

Gail Ridenour

Co-Principal

The Ridenour Family Principal Oboe

Ken Bronstein

English Horn

Ken Bronstein

The Dick & Sherry Nelson English Horn

Clarinet

Erika Block

The Gordon & Rosalie Nast Principal Clarinet

Emily Prestbo

David Kappele

Bassoon

Phillip Thomas

The Brian and Marya Griffin Principal Bassoon

Jackson Stewart-DeBelly

Assistant Principal Bassoon

Terhi Miikki-Broersma

Contrabassoon

Phillip Thomas

Taylor Marie Diga-Mocorro §

Horn

Brad Bigelow

The George and Crystal Mills Principal Horn

Jack Champagne

Kristi Kilgore

Greg Verbarendse

Trumpet

Karolyn Labes

The Bill & Leslie McRoberts Principal Trumpet

Del Vande Kerk

Alex Marbach §

Steve Sperry

Assistant Principal Trumpet

Trombone

Phil Heft

The Wendy Bohlke & Brian Hanson Principal Trombone

Brian Thomson

Bass Trombone

Bob Gray

Emily Asher §

Tuba

Mark Lindenbaum

The Marty & Gail Haines Principal Tuba

Timpani

Stephanie L. Straight

Principal Timpani

Percussion

Kay Reilly

Co-Principal

The Valerie McWhorter & Dean Altschuler Principal Percussion

Melanie Sehman

Co-Principal

The Barbara & Michael Ryan Principal Percussion

Jamie Ihler

Harp

Jill Whitman

The Cinda & Stuart Zemel Principal Harp

Keyboard

Andrea Rackl

The Sibyl Sanford Principal Keyboard

§ Substitute

There are many ways to keep the Bellingham Symphony Orchestra’s legacy strong, regardless of your means. We are proud to announce that we now have our own endowment available for legacy giving!

“Our Legacy Society is composed of remarkable, passionate individuals who care deeply about the future of the Symphony and the continuation of our educational programs in the community for years to come.” - Music Director Yaniv Attar

We are so very grateful to our legacy society members, who make it possible for us to keep the music alive, and to encourage musicians of the future. For a list of all our generous contributors and legacy society members, please click here.

For more information, contact us at (360) 756-6752 or by email to executive@bellinghamsymphony.org. You can also see more about ways to give here.