Banner

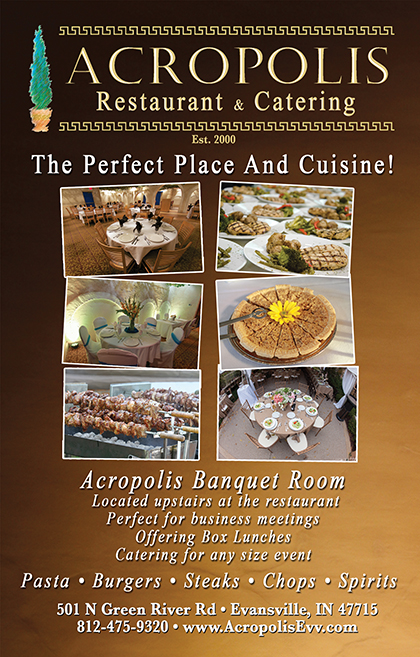

Jessie Montgomery, born 1981, is an American violinist and composer. She grew up in New York City and has garnered degrees from the Juilliard School and NYU. She has already had a long and active career teaching, performing, and composing. She co-founded the string ensemble PUBLIQuartet and has received commissions from many groups, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Sphinx Organization, and the National Choral Society. Her works have been performed by the Atlanta Symphony, the Detroit Symphony, and San Francisco Symphony. Tonight’s featured work, Banner, was commissioned in 2014, the bicentennial anniversary of the penning of the poem The Star-Spangled Banner.

As he was watching the shelling of Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor, Francis Scott Key, a 35-year-old lawyer, was so moved that he wrote a poem—three stanzas in addition to the familiar one that is sung. Interestingly, the poem fits the phrase structure of To Anacreon in Heaven, a song long popular at the time in men’s music clubs and, less politely, in pubs. Despite the punishing bombardment of the American forces, the sky DID clear in the morning, revealing the fact that the Americans had prevailed in the fight as a massive flag, 17 by 25 feet, unfurled in the dramatic sunrise.

Montgomery’s demanding score features a string quartet, surrounded by a field of string players. Of course, Montgomery’s is much more than a reworking of the original composition. She layers additional influences—a folk song, Latin music, “scratchy” string playing with cellos and basses acting as percussion instruments—to the disassembling and reconstruction of the familiar anthem. After a stormy beginning where strains of the original tune can be heard in the quartet, someone appears to “pull the plug” after about three minutes, the players sliding down the strings to silence only to re-start with renewed vigor. Montgomery herself refers to the work as a fanfare; other musicians call it a rhapsody; all descriptions point to the charged, emotional nature of the work. The composer has noted that the original “song represents a paradigm of liberty and solidarity against fierce odds, and for others it implies a contradiction between the ideals of freedom and the realities of injustice and oppression.” That contradiction is certainly a part of the multi-colored fabric of the American identity: Francis Scott Key came from a wealthy, slave-owning Maryland family and yet steadfastly believed in his poetic claim that America was “the land of the free.” Montgomery’s work acknowledges both the diverse contributions of others to the creation of an inclusive American identity as well as the charged and personal nature of “freedom” itself.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 2 in D major

German composer Ludwig van Beethoven, 1770-1827, through his unquestionable musical genius, pretty much single-handedly helped move western music from the Classical period to the Romantic era. 1802, the year that Symphony No. 2 in D major was completed, may have been a milestone in that transition. In many ways, Beethoven epitomizes the quintessential Romantic hero—shy and self-effacing yet often contentious and obdurate, a self-described loner yet spokesperson for the masses, a lover of the peace and quiet of rural rambles yet frenetic in devotion to his art. He was, in short, a man of great contradictions.

At the time, he was in love with his piano student, Giullieta Guicciardi, to whom he may have proposed. As a testament to his affection for the young woman, he dedicated the “Moonlight” Sonata (opus 27, No. 2) to the Countess, 16 years old at the time. If Beethoven did summon up the courage to propose to her, it is certain that her parents disapproved of the disheveled, temperamental musician as an appropriate match for their high-born daughter. One assumes that the piano lessons came to an end (too bad for someone for whom such a wonderful piano sonata was penned); the Countess was later married to Count Wenzel Robert Gallenberg, a man with the requisite rank and influence. Beethoven was devastated.

At the same time, after years of doctors’ visits and useless treatments, Beethoven learned that his hearing problems would be progressive and permanent. He was only 31 years old. Friends arranged for the composer to leave Vienna for the rural town of Heiligenstadt in 1802, where he could wander through the hills and work out the traumas of his life. In Heiligenstadt, along with his latest symphony, Beethoven also wrote a desperate letter to his two brothers. The letter was never sent but was spared and has come to be known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, and while not a testament it was surely a statement of despair. Not only does Beethoven lament the profound loss of hearing, but he also claims that he “is bound to be misunderstood” in the world of the hearing or of all others for that matter. Yet, as he later writes, it is because of his devotion to his art that the young composer “did not end [his] life by suicide.”

So, what is to come of this painful period in the composer’s life? Amazingly, this crisis results in nothing less than what Hector Berlioz calls a symphony that “smiles” throughout its long and complicated development. It is one of the most joyous works that the composer wrote; it is written in major keys throughout (with a momentary minor-key thunderous premonition of the Ninth Symphony in the first minutes of the Adagio molto before that movement breaks into the supple Allegro con brio). In layout, Beethoven’s symphony is not unlike Haydn’s late symphonies—a long introduction, often slow, leads into a first, fast movement; the instrumentation is similar; there are four movements, although Beethoven dismisses the Minuet for an ebullient Scherzo—yet the sound is definitely new, definitively Beethoven. The first performance of the symphony took place in 1803 at a marathon-length concert—Symphony No. 2, the Piano Concerto No. 3 (with the composer as soloist), and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives—all new music to the audience. As you might imagine the critics were at best nonplussed. One of the chief sticking points was the opening motif in the fourth movement—the instrumentalists play a high note with a preceding grace note then reach low in the register for a gravelly trill and a bumpy finish. Some listeners heard the disagreeable rumble of Beethoven’s stomach in that motif; others felt the figure was the equivalent of a musical fart—both inappropriate to the staid musical minds of the time. Another way to hear that motif—and the entire symphony for that matter—is as a composition full of humor and vitality and as a triumph of the will of the artistic spirit in a man showered with more than his fair share of adversity.