DEATH OF THE POET

DEATH OF THE POET

Death of the Poet Program Note Written by TJ Cole

Two years prior to composing the piece, I saw “Death of the Poet Walter Rheiner” by Conrad Felixmüller at the Art Institute of Chicago. The painting was enormous, with a contorted figure suspended in the air, but the colors were what struck me the most. The artist used vibrant and deep blues, purples, reds and greens to portray this night scene. I’ve always connected strongly to colors, so my reaction to the painting was an emotional one. The figure in the painting, Walter Rheiner, was a poet and close friend of Felixmüller. The painting shows Rheiner’s last moments before his death, which inspired me to compose Death of the Poet in the style of an Elegy.

CELLO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, RV 418, OP. 26, NO. 17

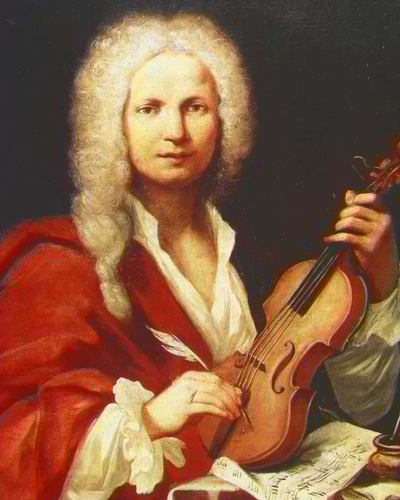

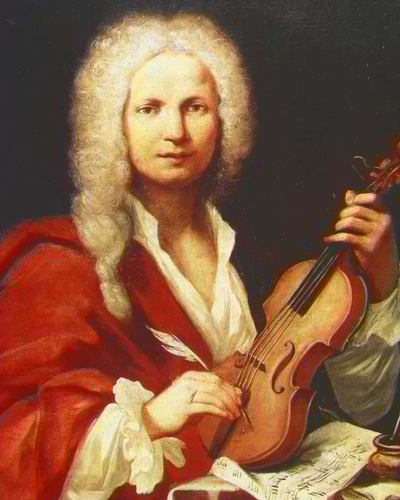

CELLO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, RV 418, OP. 26, NO. 17ANTONIO VIVALDI

Antonio Vivaldi was born in the Republic of Venice (now Italy) in 1678 and died in 1741. A virtuoso violinist and prolific composer, Vivaldi trained for the priesthood and was ordained in 1703. That same year he was appointed music master at Ospedale della Pietà, an orphanage for girls. As you might expect, the Ospedale, with Vivaldi as guiding musical force, became famous for creating highly skilled young musicians, and Vivaldi composed music—both vocal and instrumental—for his charges to perform. Supposedly suffering from a respiratory ailment that interfered with his speaking, Vivaldi did not celebrate mass or for that matter assume other priestly responsibilities, which allowed him to dedicate his energies to creating music.

And Vivaldi created a lot of music—at least 500 concerti for various instruments, more than 90 sonatas, and somewhere around 50 operas, not to mention secular and sacred vocal music. At his death, his collected works filled 27 bound volumes.

Tonight’s program features a concerto, a musical form that Vivaldi did much to develop and perfect. The composition is framed in a now-standard three-movement format: two fast movements are separated by a slower, more reflective movement, usually in a related key (in this case, D minor). Typical of baroque concerti, the cello concerto in A minor makes use of the ritornello form. The strings introduce the first movement, and their initial strain of 22 measures ends with a flourish of fast notes that establish the key of A minor, at which point the soloist enters, accompanied by continuo. Virtuosi passages for the soloist lead to the next orchestra entrance (the “return” of ritornello), and the interplay continues.

Though highly productive throughout his life where he was engaged by patrons throughout Europe, Vivaldi and his music—particularly his operas—fell out of fashion later in his lifetime, and he ended his life in relative poverty. Recent interest in his vocal music has nonetheless revealed great artistry and drama in his vocal output. Witness the breathtaking (quite literally) performance of Cecilia Bartoli and Il Giardino Armonico (orchestra of period instruments) in “Viva Vivaldi” (easily accessed on Youtube). And by now “The Four Seasons” has, worldwide, become a touchstone of artistic excellence.

FRATRES FOR CELLO, STRINGS AND PERCUSSION

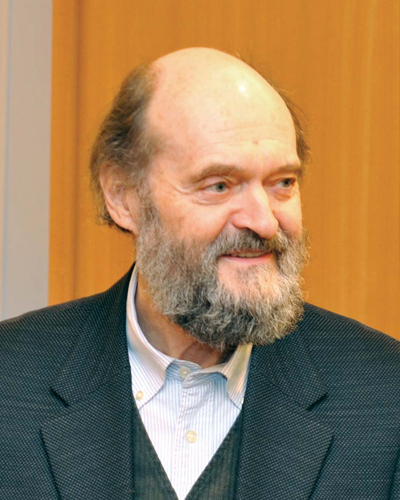

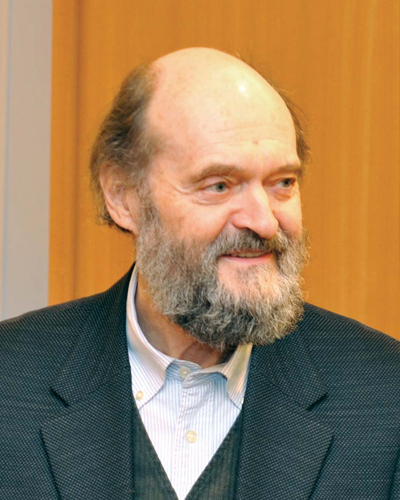

FRATRES FOR CELLO, STRINGS AND PERCUSSIONARVO PÄRT

Estonian Arvo Pärt was born in 1935. By many accounts, he is the world’s most performed contemporary composer. A devout Eastern Orthodox Christian, Pärt is often considered a mystic though he denies this attribution. His early compositions were inspired by his study of serial music (think Arnold Schönberg and the 12-tone scale), yet by the 1970s he turned his creative attention definitively to exploring the musical possibilities of simple chords, unusual timbres, massively slow development of musical ideas. Some critics have referred to his music as “holy minimalism,” a description with which the composer takes issue, despite obvious elements of Gregorian chant and Orthodox liturgical music (which he studied closely for a number of years) in his compositions. Others have labelled Pärt “neo-Baroque,” perhaps because of his penchant for the elaboration of simple musical elements. There seems to be no easy fit for Pärt, which may be one reason that people find his music endlessly inventive and appealing.

Tonight’s composition, “Fratres” (“Brothers”), was written in 1977; the composer indicated no fixed instrumentation. There are versions for string orchestra, string quartet, strings and percussion, violin (or viola or cello) and piano. What all versions share is a startling contrast between moments of frenetic musical activity and of meditative quiet. Pärt himself describes this work as part of his “tintinnabuli” style, one inspired by the sound of bells, their clang and rippling resonance (Think of Edgar Allen Poe’s poem “The Bells”: “the tintinnabulation that so musically wells”). Not surprisingly, “Fratres” appears in many films and documentaries.

Many listeners find spiritual comfort in Pärt’s evocative music. Some of that solace must derive from the composer’s approach to novel sounds and to the musical use of silence. In a recent interview with National Public Radio Pärt was asked about silence in his music. The Estonian composer answered: “Silence is like fertile soil, which. . .awaits our creative act, our seed.”

20.cs.png)

SELECTIONS FROM PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION

SELECTIONS FROM PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITIONMODEST MUSSORGSKY/Arranged by Robert Patterson

Along with fellow Russians Alexandr Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Nicolay Rimsky-Korsakov, and César Cui, composer Modest Mussorgsky formed a famous group that called itself The Five; the members strove to create a Russian, nationalist school of music and to break from controlling European cultural traditions.

Modest Mussorgsky was born in 1839 and lived until 1881, dying in poverty and isolation. Though he had been sent to a military academy for training (and in fact became a lieutenant), he also learned piano from his mother and had private instruction in composition with Anton Gerke a well-known academic. Mussorgsky’s roots were in the peasantry, and it was to this background that he turned for inspiration for his highly original music. From his early youth, Mussorgsky learned of Russian folk and fairy tales, including, for example, the story of a witch who lured children to her hut in order to consume them (only in a few versions do the children get the best of the witch).

His music began to gain fame by 1866, when “Night on Bald Mountain” was written. Three years later, he began work on his great opera “Boris Godunov”; Mussorgsky himself fashioned the libretto from the poetry of Pushkin. In 1874, the death of his friend Victor Hartmann inspired Mussorgsky to compose a series of piano compositions based on his presence at an exhibition of the painter’s works—the “Pictures at (or from) an Exhibition.” Hartmann and Mussorgsky both believed that Russian culture had been in thrall to European culture; both strove to incorporate folk and popular elements in their artistic work.

The stately “Opening Promenade” recalls the composer as he wanders through the gallery. The promenade recurs several times in the course of the composition and, each time set a little differently, accompanies and describes the musician as he experiences each of his friend’s works. “The Gnome” portrays an imp with misshapen legs, puckish and somewhat perverse. In Mussorgsky’s music you can hear the gnome shriek as well. The following selection, “The Old Castle,” depicts a troubadour playing his sorrowful love song. The rhythm, a 6/8 siciliano, is Italian, but the song and sound are Russian. Baba Yaga is a famous witch who appears in many folk traditions, typically inhabiting a dingy cottage in deep, forbidden woods and luring wayward children to their doom. Hartmann’s “Baba Yaga” was a wooden clock whose body resembled a hut supported by spindly legs. At the end of “Baba Yaga” a dramatic and cacophonous race up the musical scale explodes into the final work, “The Great Gate of Kiev.” In his painting Hartmann presents a design of a magnificent gate for that city. The gate is crowned by a cupola in the form of a traditional Russian helmet, and Mussorgsky takes elements of Russian liturgical chant to add to the solemnity. Both artists affirm the triumph—and possibility—of a Russian nationalist tradition.

Mussorgsky’s piano composition has been transcribed for orchestra by many musicians, most notably Maurice Ravel in 1922. Tonight’s version was created for wind ensemble by Robert Patterson.

DEATH OF THE POET

DEATH OF THE POET CELLO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, RV 418, OP. 26, NO. 17

CELLO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, RV 418, OP. 26, NO. 17 FRATRES FOR CELLO, STRINGS AND PERCUSSION

FRATRES FOR CELLO, STRINGS AND PERCUSSION SELECTIONS FROM PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION

SELECTIONS FROM PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION

20.mod.png)

20.jbi.png)

20.mod.png)

20.jbi.png)

20.mod.png)

20.cs.png)

20.mod.png)

20.jbi.png)

20.jbi.png)