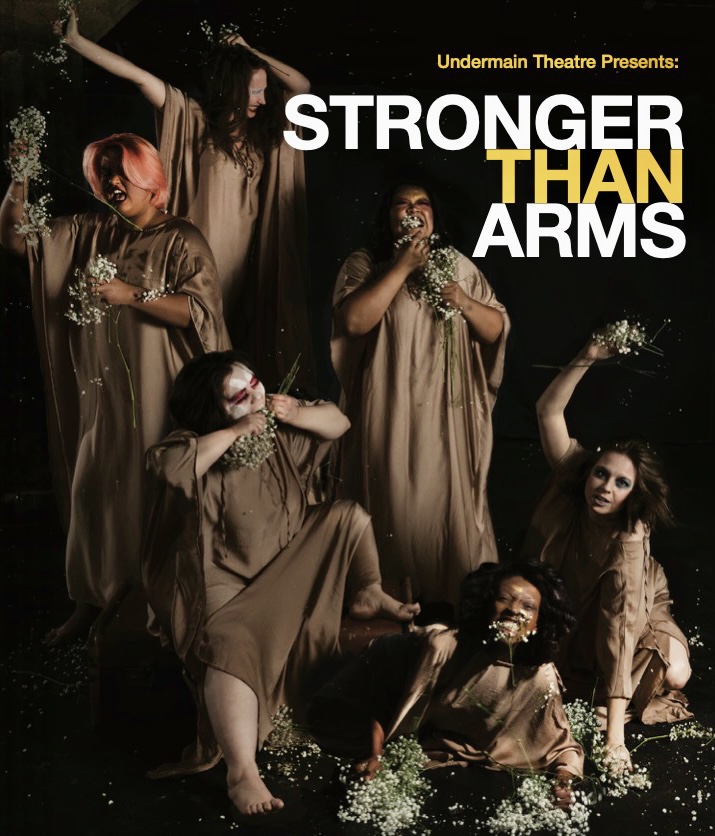

Undermain Theatre and the Danielle Georgiou Dance group are proud to present Stronger Than Arms, a new adaptation of Aeschylus’s Seven Against Thebes done in the inimitable style of DGDG. Writer/director/choreographer Danielle Georgiou and writer Justin Locklear will dive into the spiritual and political burdens placed on the chorus of Theban citizens. As the generational conflicts of territory and birthright ravage the cities around them, the chorus is divided, revealing their individual conflicts and motivations. The title stems from the line, “Fear is stronger than arms,” while the story points to the power of humanity’s worst enemy, unconquerable fear, and reveals that there could be something stronger—the willingness to change. Told through poetic verse, dance, and multi-media, Stronger Than Arms examines the universal themes of myth, status, aggression, and fate. Expect the unexpected!

Stronger Than Arms runs appoximately 60 minutes with no intermission.

We acknowledge the land beneath our feet as the ancestral home of many Indigenous Peoples, including the Caddo, Wichita, Tawakoni, and Kiikaapoi, as well as the tribes that may have lived here and roamed the area—including Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache—and those Indigenous people whose names we don’t know anymore. We honor, revere, and respect those who were stewards of this land long before we made it our home.

It is the day of battle. The sons of the disgraced King Oedipus, Eteocles and Polynices, fight for the crown of Thebes. Unable to share in ruling their city, Eteocles banished Polynices, who then found refuge and political support from the neighboring power of Argos. The kings of Argos, and their Argive armies, have come to Thebes to support Polynices’ claim to power. This tumultuous political scene has thrown Thebes into disarray, its citizens scrambling to fight for their own safety. The two daughters of Oedipus, Antigone and Ismene, as well as their cousin Pyrrhos, seek shelter in the temple. In their pleas to the gods, the entire city seeks an answer — will this war finally end the curse of Oedipus?

In 2017, during a trip to visit family in Cyprus, I was fortunate enough to attend the National Theatre of Northern Greece’s production of Seven Against Thebes. And while this play is not commonly performed, it was my second time to see it—the first was in 2001, on a previous trip to Cyprus. To set the scene, I was sitting near the top of the Kourion Amphitheater, maintained among the unearthed ruins of the ancient city, nestled in the hillside above Episkopi Bay. The last stragglers off a tour bus arrived just before sunset, and as the sky grew dark, the completely packed audience buzzed with anticipation. Sensing that the show was soon to start, we shared the urge to grow quiet, listen for the show to begin, and look around for actors to emerge. As we only sometimes experience, a true silence, which is, in fact, quite loud, fell over the crowd. Carried by a swift evening breeze from the beach a mile away, the rushing crescendo of crashing waves filled our ears. It sounded electric. I was so grateful to have at least partially forgotten the feeling from the last time so that this moment was still new and exhilarating. And there, before the show began, I was lucky enough to have a quiet mind and to see myself. A never-guaranteed gift. So, where was I?

Kourion, a city in southern Cyprus, is just down the coast from a dramatic outcropping which would later be named Aphrodite’s Rock; she, the goddess of the island itself. The city was founded by settlers from Argos, escaping the conflicts of Mycenaean Greece, around the 12th century BCE. In the ensuing rush of time and history, the lands of Cyprus would be conquered, recovered, re-conquered, invaded, et cetera. All the while, this theater, this fabulous tool of democracy and civilization, experienced similar seasons of growth and decay. And now, three thousand years later, humans still scrutinize the ancient myths that traveled throughout the oral tradition of these Mediterranean lands.

Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes was the third installment of a tetralogy concerning the myth of Oedipus—two other dramas preceded it, and a satyr play followed. Since all the other parts of the tetralogy are lost, Seven appears bare and mechanical, relying on an editorial foundation that we can no longer reference. Even the original ending, which we no longer have, was altered to suit Sophocles’ Antigone, written well after Aeschylus’ death. The script, benefiting from centuries of maintenance from historians and academia, survives, even though it was never genuinely celebrated for its merit as a play.

Back in 2017, watching the show float through tragedy, to comedy, to history, to judgment, I felt a wave of reality crest over me. The play asked many questions I hadn’t considered before, and the new ending refused to answer them. I knew right then and there, in a sea of sun-kissed Cypriots, I was going to create a new telling of this myth.

Greek tragedy is a presentation of the ambiguity of justice—the ambiguity of human’s understanding of themselves. Seven Against Thebes pays heavy tribute to the weight of the legacy of Oedipus. While the questions of free will and violence are challenging and dynamic, I saw an opportunity to peer into the lives of those who inherit that violence, those who must ponder that free will.

What’s with all the Flamingos?

Flamingos are elegant yet bizarre, trendy and modern, and incredibly ancient in symbolism. You’ve heard of the myth of the Phoenix, but do you know the different traditions which created it? In Greek, a flamingo is called phoinikopteros (φοινικόπτερος), or “Phoenician-winged-bird,” referring to a dye, Tyrian Purple, which originated from the Phoenician civilization. In North Africa, the migration patterns of Flamingos grew into a myth of a mighty bird, flying to a specific place at rare times, building a fire, and setting itself aflame, only to re-emerge three days later, covered in ash.

“Flame”-ingos (our English word coming from flamma in Spanish) develop their rich pink-coral color from their diverse seafood diet, even using the color as make-up during mating season to deepen their plumage. After laying eggs, the birds slowly lose the intensity of their color, returning to an ashen off-white. The bizarre shift in color inspired the images of flames, but what about stories of Flamingos building fires? Many Flamingos live in areas where the temperature of the ground is too hot for their eggs to survive, so they adapted by building pyre-esque nests which keep the eggs cool. The stories align with an original Egyptian myth of the Bennu Bird, said to herald the flooding of the Nile, bringing new life, wealth, and fertility. The waterfowl were seen as the living symbol of Osiris and worshipped as a god!

The myth of Phoenix grew in popularity, making its way into Greek literature(though perhaps not the first time) with Herodotus’ writings in the fifth century BCE. After learning of the myth in Egypt, he wrote that the people of Heliopolis spoke of the bird, every 500 years, building a fire, burning its body, coming back to life, and bringing its corpse as a sacrifice to the temple. The visually commanding myth has emerged throughout history as a symbol of almost every major religion, continually recalling the images of rebirth, often painful, and the defeat of mortality.

A final, fascinating detail is that the Greeks also viewed the tongue of the Flamingo as a delicacy, giving its consumer long life, other god-like powers, and possibly, the ability to heal the wounds of one’s ancestors. This fountain of youth—in bird form—paralleled their belief in “Metempsychosis,” or “the transmigration of the soul,” a cyclical journey of the soul from body to body throughout time. The Flamingo, like the one in your lawn or printed across your pool float, was a god-like wonder, inspiring the human imagination for thousands of years, and still fascinates us today!

Thank you to Dallas College-Eastfield Campus Departments of Theatre and Dance, Arts Mission Oak Cliff, and Heather Alley.

Donor Roll of Honor - Leadership Circle

September 1, 2020 - September 30, 2021

Undermain Theatre and its Board of Trustees recognize the contributions of our Leadership Circle Donors who give generously to support the work of the theatre. Thank you for helping us bring exciting and innovative new work and classic productions to our Dallas community as we return to live performance in the basement.

Pillar ($10,000 - $24,999)

Anonymous (1)

Ford and Cece Lacy

Deborah and Jim Nugent

Benefactor ($5,000 – $9,999)

Barbara and Mark Ashworth

Ida Jane and Doug Bailey

Kay and Elliot Cattarulla

The Bryant and Nancy Hanley Foundation

Pat and Jed Rosenthal

Deborah and Craig Sutton

Patron ($2,500 – $4,999)

Cynthia and Jay Anthony

Joleen and Jim Chambers

Sandra Johnigan and Don Ellwood

Mary Lee and Ron Hull

Rusty and John Jaggers

Donovan Miller and Aaron Thomas

Karol and Larry Omlor

Mary and Timothy Ritter

Maxine and Greg Spencer

Norma and Don Stone

Thespian ($1,200 – $2,499)

Anonymous (2)

Tom Adams

Melissa Auberty

Carole Braden

Clare and George Burch

Kathryn and Graham Greene

Rose Hultgren

Ashley Kisner

Linda Patston

Christine and Richard Rogoff

Mary K Vernon

Karen and Jim Wiley

Barbara and Barry Wolfe

For more information on the benefits of becoming a donor to Undermain Theatre, please click here.

To discuss Individual Donation opportunities, please contact Undermain’s Development Office by email at development@undermain.org.

Corporations, Foundations and Government

September 1, 2020 - September 30, 2021

$40,000 and above

Anonymous (2)

City of Dallas, Office of Arts and Culture

$10,000 – $39,999

Jonathan P. Formanek Foundation

TACA

The Shubert Foundation, Inc

$1,000 – $9,999

Anthony Family Foundation

Jaggers Family Fund of The Dallas Foundation

O. Darwin and Myra N. Smith Fund of The Dallas Foundation in honor of Adina L. Smith

The Ben E. Keith Foundation

The Moody Fund for the Arts

The Nancy and John Solano Advised Fund at The Dallas Foundation

Texas Commission on the Arts

Up to $1,000

Louise W. Kahn Endowment Fund of The Dallas Foundation

Communities Foundation of Texas

Texas Brand Bank

Tommy’s Terrific Carwash / Kim and Tom Miller

CORPORATE PARTNERSHIPS

Undermain Theatre welcomes the support of companies which enables us to present the highest quality theatre at a price affordable to all. Benefits for your company include Internal Recognition, External Promotions, and Hospitality Benefits for you to use to entertain clients or employees. Our Development Team wants to work with you on a customized package that benefits your company, its employees, and the Undermain. Please contact us by email at development@undermain.org for more information.

Donor Roll of Honor

September 1, 2020 - September 31, 2021

Artist ($600 – $1,199)

Diane and Harold Brierley

Mark Craig

Dan Culver

Diane and Larry Finstrom

Michelle and Donald Hungerford

Shannon Kearns

Barbara and Sam McKenney

Joann and Lin Medlin

Charles Dee Mitchell

Julie Pao and Dale Odell

Wayne Ruhter

Nancy and John Solana

Jana and Bill Swart

Christiane Baud and Donald Hilgemann

Eric Bird

Peggy Carr

Marsha and Don Coburn

Tori and Mike Correll

Karen and Shelby Davenport

Diana Dutton

Julie England

Bess and Robert Enloe

Elizabeth Erkel

Cathey Fears and Mark Blaquiere

Karen and Sean Fitzgerald

Veletta Forsythe Lill and John Lill

Riki and Ezra Greenspan

Kathy and Steve Haas

Jack Hagler

Martha Heimberg and Ron Sekerak

Mary Hestand and Alan Tubbs

Rachel Hytken and Jeff Givens

Lee and Bryan Jones

Victoria Jones and R Bruce Elliott

Kristine Kelly in honor of Marlo Mysliwiec

Dylan Key

Rebekka Koepke

Victor Kralisz

Nell and Tim Langford

Teresa and Kyle Lemieux

Eleanor Lindsay and Randall Bonifay

Lou Michaels and John Davies

Matthew Posey

Ashley Randall and Jonathan Brooks

Debby and Kevin Rogers

Jennifer Schroeder and David Popple

Madeline and Reginald Schwoch

Jenny Keller and Richard Scotch

Stephen Seybold

Joan K. Schellenberg

Nancy Shelton

Lois Slate

Kathy Stewart

Susan Thompson

Laurie and Rob Tranchin

Marlene Tubbs

For more information on the benefits of becoming a donor to Undermain Theatre, please click here.

To discuss Individual Donation opportunities, please contact Undermain’s Development Office at development@undermain.org

Board of Trustees 2020-2021

|

Johnette Alter |

Karol Omlor |

|

Joleen Chambers |

Linda Patston |

|

Bruce DuBose |

Anthony L. Ramirez |

|

Graham Greene |

Pat Rosenthal |

|

Patricia Hackler |

Steve Sears |

|

Ashley Kisner |

Katherine Sharp |

|

Tim Langford |

Bill Swart |

|

Lin Medlin |

Mary K Vernon |

|

Deborah Nugent |

Craig Walters |

| Angus Wynne III |

phone: 214-747-1424 or 214-747-5515

email: mail@undermain.org

mail: PO Box 140193, Dallas TX 75214

The Undermain Theatre offices are closed at this time. For assistance with ticketing or accessing your virtual streaming performances, please email the Box Office at boxoffice@undermain.org. The Box Office email is monitored daily during the run of this production.