BROADCAST PRESENTATION

2020-21 Season Bonus Episode No. 1

S1.EB1 In Focus Season 1, Bonus Episode 1

_____________________

Sonata & Serenade

Broadcast Premiere Date/Time:

Thursday, February 11, 2021, at 7 p.m.

featuring

Mitsuko Uchida, piano

in solo performance at London’s Wigmore Hall

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Piano Sonata in C major, D.840 (unfinished)

1. Moderato

2. Andante

paired with

The Cleveland Orchestra

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

performing at Severance Hall

WOLFGANG AMADÈ MOZART (1756-1791)

Eine kleine Nachtmusik [A Little Serenade]

Serenade No. 13 in G major, for strings, K.525

1. Allegro

2. Romanze: Andante

3. Menuetto: Allegretto

4. Rondo: Allegro

In addition to the concert performances, each episode of In Focus includes behind-the-scenes interviews and features about the music and musicmaking.

Each In Focus broadcast presentation is available for viewing for three months from its premiere.

_____________________

With thanks to these funding partners:

Presenting Sponsor:

The J.M. Smucker Company

Digital & Seasons Sponsors:

Ohio CAT

Jones Day Foundation

Medical Mutual

In Focus Digital Partner:

The Dr. M.Lee Pearce Foundation, Inc.

Episode Sponsor:

Mitsuko Uchida's performance

is generously sponsored by

Dr. and Mrs. Hiroyuki Fujita

I N T H I S S P E C I A L bonus episode, pianist Mitsuko Uchida is showcased in a solo performance filmed especially for Cleveland Orchestra audiences on January 4, 2021. She plays one of Schubert’s most mesmerizing sonatas, an encore of a work she presented in Cleveland in 2019.

Uchida’s brilliant solo playing is paired with one of Mozart’s most popular and well-known works, his Eine kleine Nachtmusik. “Nachtmusik” literally means “night music,” but more simply suggests music for serenading evening guests. Here Mozart’s richness for invention and uplifting joy carries you forward through four exquisite movements for strings. Franz Welser-Möst leads the Orchestra's string section in a performance filmed this past fall, in October 2020.

PIANO SONATA IN C MAJOR, D.840

(unfinished; two existing movements)

by Franz Schubert (1797-2828)

Composed: 1825, incomplete

Duration: almost 30 minutes

________________________________

A C R O S S H I S L I F E T I M E, Schubert wrote two dozen sonatas for the piano, about a dozen fewer than Beethoven. In addition, among the many fragmentary pieces that have come down to us from Schubert’s pen are many single movements — andantes, scherzos, variations, fugues, etc. — which were most likely intended as sonata movements, but were never paired with other movements or were abandoned for reasons we cannot know.

The “Unfinished” label attached to the famous Symphony in B minor, D.759, could in fact be applied to a great many pieces by Schubert, either because they were actually never completed or because so many pieces were still unpublished at his death that their manuscripts were split up and, in many cases, partially lost.

The Sonata in C major, D.840, featured in this performance, is a related case because the last two movements survive as fragments (just as a Scherzo and Finale do for the “Unfinished” Symphony). For the Sonata in C major, the first two movements are complete. And, although one should never entertain the idea of a “perfect torso” — an idea applied to broken ancient statues as embodying “perfection” in their incompleteness — and, even though Schubert rarely deviated from the basic four-movement structure for sonatas and symphonies as laid down by Beethoven’s early music, it is quite satisfying to hear two genuine movements in this instance (without the two additional movements more recently completed by other hands in imitation of Schubert’s inventive frame of mind).

In Schubert’s time, piano sonatas were domestic, not public, music. “Schubert was not an elegant pianist but he was a safe and very fluent one,” wrote his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner. Not a virtuoso, perhaps, but then he would never have played this sometimes very difficult music in public. Very little of his output was published during his lifetime, even though there was a lively market for piano music and songs. His sonatas were thus hidden from the next generation of composer-pianists, such as Chopin and Liszt, and contributed very little — unlike Beethoven’s sonatas — to the ongoing historical development of the piano.

But perhaps this does not matter. There is a wayward, private character in much of Schubert’s music, when he seems to be following the thread of his inventiveness down new, secret paths. This is music that can, thus, speak very directly to us, unencumbered by its role in history.

We follow the composer’s lead and accept the leisurely pace at which many movements reach their goal, with unexpected twists and turns at every corner. Some of these twists and turns, being the teasing avoidance of the expected key tonalities, are evident only to the player and the sharp-eared analyst, but will nevertheless be the source of infinite pleasure to many listeners.

THE MUSIC

In 1825, Schubert wrote a group of piano sonatas, of which the Sonata in C major is the most impressive, despite being incomplete. With only two movements, it leaves an impression of grandeur and strength — a feeling that might be diminished if the two final movements had been completed. Both of the movements he finished display puzzling elements that Schubert must have felt unable to resolve. The composer was never mindful enough (to future historians and musicologists) to write “hopeless ideas,” “too gloomy,” “too busy,” or even “I lost the manuscript” on his incomplete movements. What stopped him from completing the two other movements? — we can only guess.

His reputation was growing, at least in Vienna, and the popularity of Schubertiads — mixed programs of songs and piano music played in private houses — was spreading. He spent the summer months of 1825 in the Austrian countryside with his friends, composing every day, and it was probably in that year that he wrote what we know as his “Great” C-major Symphony, D.944. (It is always helpful to keep in mind that the English translation of the nickname to “Great” misses some portion of the depth and breadth of the German word “Grosse,” meaning “big and magnificent” rather than the English sense of “great” to mean “very good.”)

At all events, the two movements of the Sonata in C major, composed in April 1825, display a spaciousness that is scarcely to be found at all in Schubert’s earlier music, but so very much became a strong feature of his late music.

By establishing a stately tempo and allowing his themes to spread languidly from one page to the next, Schubert creates a haunting atmosphere, as if the listener were captive to some inexorable force. Part of this is achieved from a sense of pulse, often resembling a march tempo. This can continue for long periods unchanging, relentless even, like a pendulum, and it can sometimes generate climaxes of blinding intensity, the resolution of which is often gracefully achieved by a magical change of key and texture, returning to the serene mood with which the movement began.

Serenity in Schubert is wonderfully pleasing to the ear, but it can also hide an inner disturbance masked by a virtuoso control of keys and dynamics. Such things in Beethoven represent the loud voice of a strong man, whereas in Schubert the outbursts are almost involuntary, like tremors felt beneath a peaceful landscape. In both these movements, the variety of underlying accompanying figurations is as much to be admired as the freshness of the themes — a feature that has made his songs an essential diet for any singer.

—Hugh Macdonald © 2021

Mitsuko Uchida is a performer who brings deep insight into the music she plays through her own search for truth and beauty. She is particularly noted as a peerless interpreter of the works of Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, and Schubert, both in the concert hall and on recordings, and has also illuminated the music of Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and György Kurtág for a new generation of listeners.

Ms. Uchida made her Cleveland Orchestra debut in February 1990, and since that time has performed frequently with the Orchestra at Severance Hall, at Blossom, and on tour in Europe and Japan. She made her Cleveland Orchestra conducting debut in 1998, and subsequently led performances from the keyboard of all of Mozart’s solo piano concertos as artist-in-residence for five seasons (2002-07). In a special recording project with the Orchestra and Decca, Ms. Uchida revisited a number of Mozart concertos, with these albums winning acclaim and a Grammy Award.

Ms. Uchida performs throughout the world with many different partners. In 2017, she embarked on a two-year Schubert Sonata series, featuring twelve of the composer’s major works, which she toured to renowned venues across Europe and North America. Recent season performances have also included returns to the Salzburg and Edinburgh Festivals and concerto appearances with the Berlin Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and in Cleveland. In 2016, she was appointed an artistic partner to the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and began a five-year series of concerts directing Mozart concertos from the keyboard with that ensemble in tours of major European venues and Japan.

Mitsuko Uchida records exclusively for Decca, and her extensive discography includes the complete Mozart and Schubert piano sonatas. Her recording of Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto with Pierre Boulez and The Cleveland Orchestra won four awards, including one from Gramophone for best concerto recording. Five of her most recent albums were recorded live at Severance Hall with The Cleveland Orchestra and feature ten of Mozart’s piano concertos.

Ms. Uchida’s discography ranges widely, from Mozart to Debussy, and Beethoven to Berg. Albums include the complete Mozart piano sonatas and piano concertos (with the English Chamber Orchestra), the complete Schubert piano sonatas, Debussy’s Études, the five Beethoven piano concertos with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, an album of Mozart violin sonatas with Mark Steinberg, the song cycle Die schöne Müllerin with Ian Bostridge for EMI, and the final five Beethoven piano sonatas.

Mitsuko Uchida has demonstrated a long-standing commitment to aiding the development of young musicians and is a trustee of the Borletti-Buitoni Trust. She is also artistic director of the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont. In June 2009, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

EINE KLEINE NACHTMUSIK

["A Little Night Music"

or "A Little Serenade"]

String Serenade No. 13 in G major, K.525

by Wolfgang Amadè Mozart (1756-1791)

Composed: 1787

Scored for: four-part strings

Duration: about 20 minutes

Filmed: October 2020, at Severance Hall

________________________________

I N S A L Z B U R G, Mozart’s birthplace, you can hear this piece as muzak from every street corner. It is Mozart’s most popular work in our modern world. And, perhaps, it is also his most perfect work — keenly built with contrasting themes, carefully detailed (but without fussiness), beautifully proportioned, and filled with melodic gift.

Yet nobody knows why he wrote it, and we are left guessing what prompted him to turn out so finely chiseled an example of his genius. We do know that he finished this string serenade on August 10, 1787, in Vienna, as he entered it into his personal catalog of compositions. He also noted that it consisted of five movements, a fact that always shocks those who are thoroughly familiar with it in its four-movement version.

In the autograph score, a page is missing immediately after the first movement where another minuet and trio once existed. Nobody knows who removed it, or when or why.

It may also be a shock to learn that the Romance was Mozart’s second attempt at a slow movement; sixteen measures of an effort to get this movement going (quite differently) are to be found in the Mozarteum in Salzburg, among its extensive collection of pieces Mozart started but never finished.

Such fragments always prompt the question, What’s wrong with this one? Alas, he never wrote on any of these unfinished scraps: Too long, Poor tune, Wrong key, or any such explanation of his thinking. We must simply take note that a composer who has often been said to be inspired by a direct hot line from the Almighty was a human being afterall, who sometimes made what he regarded as mistakes or lesser efforts, even if we might wish he had persisted with a promising start.

In the summer of 1787, Mozart was hard at work on the opera Don Giovanni, commissioned to help celebrate a royal wedding in Prague. Some scholars regard Eine kleine Nachtmusik as a tribute to Mozart’s father, who had died shortly before, but it is much more likely that he interrupted work on his opera to respond to a commission for a short work of the serenade type to be played at a noble house. It is on a very small scale, without winds of any kind, and is close to being a string quartet in which a larger group of the strings can join in. What more suitable work for an elegant soirée could be imagined? What a mighty distance from there to the muzak in a Salzburg pizzeria! And yet, this piece is of such solid value that it continues to reward and delight listeners and performers alike with its creativity and freshness.

THE MUSIC

The opening of the first movement can seem surprising, because its musical outlines seem so obvious. Mozart more often replied to this kind of firm opening gesture with a soft, expressive phrase, but here the response is a satirical up-ending of the opening phrase, still played with force. The movement’s second subject puts the violins in octaves, a dark effect Mozart never used in his string quartets. It seems darker still in the recapitulation.

Other wonders can be heard in the middle section of the Romance second movment — a quasi-canonic dialog between first violins and basses in the minor key. The middle section (Trio) of the Minuet third movement, with its smooth flowing melody, is equally deft and interesting.

The oddity of a Rondo last movement, which is not really a rondo (of alternating variations), but in a clear sonata form with its themes juggled around and a coda added. The ending feels like a bigger work, rather than of “a little night music” (meaning before- or after-dinner music) to accompany the conversations of Mozart’s patron and friends.

—program note by Hugh Macdonald © 2021

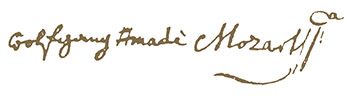

M O Z A R T was baptized as Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus

Mozart. His first two baptismal names, Johannes Chrysostomus, represent his saints’ names, following the custom of the Roman Catholic Church at the time.

In practice, his family called him Wolfgang. Theophilus comes from Greek and

can be rendered as “lover of God” or “loved by God.” Amadeus is a Latin version

of this same name. Mozart most often signed his name as “Wolfgang Amadè Mozart,” saving Amadeus only as an occasional joke. At the time of his death, scholars in all fields of learning were quite enamored of Latin naming and conventions (this is the period of the classification and cataloging of life on earth into king-dom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species, etc.) and successfully “changed” his name to Amadeus. Only in recent years have we started remembering the Amadè middle name he actually preferred.

—Eric Sellen