The Cleveland Orchestra

BROADCAST PRESENTATION

2020-21 Season

S1.E9 In Focus Season 1, Episode 9

_____________________

Musical Magicians

Broadcast Premiere Date/Time:

Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 p.m.

filmed March 25-27 at Severance Hall

The Cleveland Orchestra

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Marc Damoulakis, percussion

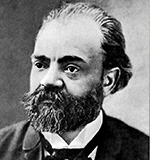

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841-1904)

String Quintet No. 2 in G major, Opus 77

(performed by string orchestra)

1. Allegro con fuoco

2. Scherzo: Allegro vivace — Trio

3. Poco andante

4. Finale: Allegro assai

JOHN CORIGLIANO (b. 1938)

Conjurer: Concerto for Percussionist

1. Candenza — I. Wood

2. Candenza — II. Metal

3. Candenza — III. Skin

In addition to the concert performances, each episode of In Focus includes behind-the-scenes interviews and features about the music and musicmaking.

Each In Focus broadcast presentation is available for viewing for three months from its premiere.

_____________________

With thanks to these funding partners:

Presenting Sponsor:

The J.M. Smucker Company

Digital & Seasons Sponsors:

Ohio CAT

Jones Day Foundation

Medical Mutual

In Focus Digital Partner:

Cleveland Clinic

The Dr. M.Lee Pearce Foundation, Inc.

_____________________

Episode Sponsor:

Marc Damoulakis's performance

is generously sponsored by

Fran and Jules Belkin

in honor of Albert and Audrey Ratner

_____________________

This episode of In Focus is dedicated

to the following donors in recognition for their

extraordinary support of The Cleveland Orchestra:

Dr. and Mrs. Herbert Kloiber

Mr. and Mrs. Michael J. Horvitz

Irad and Rebecca Carmi

T H I S P R O G R A M offers discoveries new and old, highlighting music’s magical ability to uncover and reveal pleasures, dreams, and new connections.

Antonín Dvořák wrote his Second String Quintet in 1875, just as his career was gaining international attention. Here he infuses classical traditions with musical stylings from his Bohemian homeland, bringing enlivened rhythms and sensibilities in an artful mix of thoughtful patterns and heartfelt emotions. Franz Welser-Möst leads The Cleveland Orchestra strings in a full-voiced rendition of a work originally written for string quartet and double bass.

A modern concerto by American composer John Corigliano gives the soloist a new role, of literally concocting and conjuring the musical material into existence, as if by magic. For this episode of In Focus, principal percussionist Marc Damoulakis takes up the conjuring.

STRING QUINTET No. 2 in G major, Opus 77

by Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

(performed by string orchestra)

Composed: 1875

Scored for: string quartet plus double bass

First Performance: Umělecká Beseda, Prague, March 18, 1876

Duration: about 35 minutes

________________________________

B E I N G H I M S E L F a viola player, Dvořák was generous to string players in the field of chamber music. Joined with piano, as sonata, trio, quartet, or quintet, he supplied one in each category. For strings alone, he composed that useful Terzetto for two violins and viola — useful as a fall-back when a cellist can't make it to a quartet session or concert (and beautiful, too) — as well as a dozen string quartets, three string quintets, and a string sextet.

Of the string quintets, two are for string quartet with an extra viola, like Mozart's string quintets, and one — which we are hearing in this program — is exceptional in not calling for an extra cello (something Schubert also did), but instead for a double bass, providing opportunity for a full string family.

The double bass quite distinctly changes the overall sound quality, with hints of Schubert's "Trout" Quintet, which also calls for a double bass; and it frees the cello from responsibility for the bass line. Another feature of this scoring is that the music can be played by a full string orchestra without changing any of the intended internal balance of the music.

Despite having the opus number 77, this is an early work, written at the same time as the rarely-played Symphony No. 1 and well before the Slavonic Dances made Dvořák famous beyond the borders of Bohemia. (The opus numbers were assigned by his publisher as scores were printed, with a number of early works thus receiving later numbers.)

Dvořák was thirty-four years old when he wrote this quintet, yet still searching for and filling in his own a personal musical idiom. He was hesitating to go headlong into Czech dance rhythms, even though he obviously had a wonderful sense of rhythmic vitality.

He entered the Quintet in 1875 for a prize awarded by the Artistic Circle [Umělecká Beseda] of Prague and won, with a performance given the following year. The work originally had a fifth movement, an Intermezzo, placed immediately after the opening movement and only thirty-seven bars long, but this was dropped before the first performance; it was published by itself as a Nocturne for strings, Opus 40.

The slow movement that remained, marked Poco Andante, is based on a simple scale in the key of C major, but this innocent beginning is soon replaced by more complex keys and textures, including a section in E major that has the first violins soaring high above the dutiful accompaniment from the rest. The eventual return to the C major theme of the beginning is decorated with some impatient intrusions, but the close is pure serenity.

With the finale, Dvořák settles into the fluent, energetic style which he could always call upon, keeping all the instruments busy, slipping in and out of distant keys, and allowing his lyrical gifts to show when the speedy figurations (or those playing them) need a rest.

—program note by Hugh Macdonald © 2021

CONJURER: CONCERTO FOR PERCUSSIONIST

by John Corigliano (b. 1938)

Composed: 2007

Scored for: string orchestra and percussionist, with optional brass in the third movement. The percussion instruments are arranged in three groups: wood (blocks, xylophone, etc.), metal (cymbals, vibraphone, etc.), and skin (mostly drums), each deployed movement by movement.

Duration: about 35 minutes

________________________________

N E W Y O R K composer John Corigliano is an experienced creator of concertos. He is, in fact, an experienced composer of music in almost every genre across a long and very successful career. Awards — including Pulitzer, Oscar, Grammy — and commissions have poured in upon him. And he has still found time to devote himself energetically to teaching at Juilliard and other New York schools.

It was a smart move by a consortium of orchestras (including those in Pittsburgh, Nashville, and Dallas) to commission a percussion concerto from Corigliano after he had already proven himself in concertos for oboe, clarinet, flute, and violin, and had clearly shown he could confront an unusual challenge by writing a concerto in 1997 for two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart (thus providing a complete quarter-tone scale).

A concerto for percussion was indeed a challenge, as Corigliano himself admitted: "All I could see were problems. For starters, a percussionist plays dozens of instruments. This is wonderful if his role is to color an orchestral texture: but if he (or she) is the main focus, it is terrible. . . . Most of the instruments have no pitch at all (or very little), and don't sustain a sound (like a violin or a trumpet)." Percussion's role as the provider of seasoning or reinforcement for an orchestra could not easily be reversed, Corigliano felt, to allow the orchestra to be there to amplify or complement the percussion.

"Many of my works begin this way," he wrote. "I pose a problem and write a piece as the solution. In this case, the problem is the following: How do I write a concerto for a solo percussionist playing many different instruments in which the soloist is always clearly the soloist (even with your eyes closed), and how do I write a concerto in which there are real melodies introduced by the percussionist?"

The essential feature of Corigliano's solution is the standard taxonomy of percussion into sounds created by the striking or rubbing of wood, metal, or skin. Each of the three movements is preceded by a solo cadenza, the first on wood, the second on metal, and the third on skin. The instruments are set out onstage in these groups.

Leading the wood group are the xylophone and marimba, with an assortment of wood blocks and claves.

Metal's leaders are vibraphone and chimes, both of which resonate quite strongly, conducive to melody.

Skin gives us the world of drums, pitched and unpitched, including a "talking drum" whose top and bottom skins are connected by strings which the player squeezes to produce different pitches. The hands are freely used in alternation with sticks. (The third and last movement has optional parts for brass, but any audience might feel it is plenty loud enough without. On the other hand, the strings might be happy to have some companions “against” the percussionist — but, no matter, the composer has said the piece can be played with or without brass.)

Each movement begins with a cadenza for the soloist alone containing hints of what the strings will play when they join in.

The first movement has the character of a perpetuum mobile, with a busy figure in the violas setting things in motion and serving as cover for the gap into the next movement while the soloist relocates himself in the circle of metals.

A colossal F-sharp on the chimes announces that the soloist is ready to begin the cadenza, in which a descending figure, recurrent throughout the concerto, is hammered out with full force. The strings' part of the movement moves very slowly in a haze of soft, thinly scored lines in preparation for the vibraphone's entry with something resembling a chorale. The glockenspiel floats in over ambiguous harmony. The climax is initiated by the cellos and marked by the entry of the "heavy metal" cymbals and tamtams, and the long vibraphone chorale plays the movement out.

The strings keep trying to take part in the "skin" movement, against the chatter of the talking drum. They finally assert their presence with strongly rhythmic figures as if they were pretending to be (or wishes they were) percussion. These accelerate wildly, only to be stopped by the bass drum and the double basses. Tuned timpani come to the fore, and then the rhythmic figures signal a recapitulation, accelerating as before and reaching a noisy climax where the composer loses control of the soloist and allows the player, for the rest of the movement, to "improvise a cadenza on all drums".

Once it was complete, Corigliano found that with cadenzas leading into movements, "the soloist doesn't so much introduce material as conjure it, as if by magic, from the three disparate choirs. . . . Hence the title CONJUROR."

—program note by Hugh Macdonald © 2021

Conjurer: Concerto for Percussionist and String Orchestra

The composer has written the following comments about this work . . .

When asked to compose a percussion concerto, my only reaction was horror.

All I could see were problems. While I love using a percussion battery in my orchestral writing, the very thing that makes it the perfect accent to other orchestral sonorities makes it unsatisfactory when it takes the spotlight in a concerto.

For starters, a percussionist plays dozens of instruments. Again, this is wonderful if the role is to color an orchestral texture: but if he (or she) is the main focus, it is terrible. The aural identity of the player is lost amid the myriad bangs, crashes, and splashes of the percussion arsenal. Only the visual element of one person playing all these instruments ties them together.

In addition, most of the instruments have no pitch at all (or very little), and don’t sustain a sound (like a violin or trumpet).

As a result, most percussion concertos I have heard sound like orchestral pieces with an extra-large percussion section. The melodic interest always rests with the orchestra, while the percussion plays accompanying figures around it.

Of course, one could limit oneself to writing for keyboard percussion: marimba or vibraphone, for example. Many concertos have been written like this, and the combination of using an instrument with definite pitches and restricting oneself to one instrument does focus the work on a single soloist.

I thought of all of this as I sat down to discuss my writing a percussion concerto. Obviously I had more than mixed views about this project, but something about the challenge fascinated me, too.

Many of my works begin this way. I pose a problem and write a piece as the solution. In this case, the problem is the following: How do I write a concerto for a solo percussionist playing many different instruments in which the soloist is always clearly the soloist (even with your eyes closed), and how do I write a concerto in which there are real melodies — and those melodies are introduced by the percussionist, not the orchestra?

1. CADENZA — I. WOOD

The pitched wood instruments are the xylophone and marimba. To supplement this, I constructed a “keyboard” of unpitched wooden instruments (wood block, claves, log drum, etc.) ranging from high to low and placed it in front of the marimba. The soloist could play pitched notes on the marimba and then strike unpitched notes on the wooden keyboard.

The initial cadenza starts with unpitched notes, but gradually pitched notes enter and various motives are revealed as well as ideas based upon the interval of a fifth. This interval will run through the entire concerto as a unifying force. After a climactic run, the orchestra enters, developing the 5th interval into a rather puckish theme. Soloist and orchestra develop the material and build to a climactic xylophone solo, and finally return to the opening theme.

2. CADENZA — II. METAL

The cadenza is for chimes (tubular bells) accompanied by tam-tams and suspended cymbals. It is loud and clangorous, with the motivic 5ths clashing together. The movement itself, however, is soft and long lined. The melody that will end the movement is introduced in the low register of the vibraphone, and the movement develops to a dynamic climax where the chimes return, and then subsides to a soft texture in the lower strings as the struck/bowed vibraphone plays its melody.

3. CADENZA — III. SKIN

The skin cadenza features a “talking drum” accompanied by a kick drum. The talking drum is played with the hands, and can change pitch as its sides are squeezed. Strings connect the top and bottom skins, and squeezing stretches them tighter — and raises the pitch. It provides a lively conversation with a kick drum: a very dry small bass drum played with a foot pedal and almost exclusively used as part of a jazz drum set. This cadenza starts slowly, but builds to a loud and rhythmic climax.

The movement then begins with the soloist and orchestra playing a savage rhythmic figure that accelerates to a blinding speed. A central section brings back the 5ths against a pedal timpanum that is played with the hands in a “talking drum” style. The accelerando returns, and leads to a wild and improvised cadenza using all the drums and a virtuoso finish.

________________________________

Once the concerto was complete, it occurred to me that the piece’s cadenza-into-movement form characterizes the soloist as a kind of sorcerer. The effect in performance is that the soloist doesn’t so much as introduce material as conjure it, as if by magic, from the three disparate choirs: materials which the orchestra then shares and develops; hence, the title Conjurer.

—John Corigliano (2007)

Principal Percussion

Margaret Allen Ireland Endowed Chair

The Cleveland Orchetra

Marc Damoulakis joined The Cleveland Orchestra in August 2006 and was appointed to the principal percussion chair in 2013. He also teaches as a faculty member at the Cleveland Institute of Music, presents clinics, masterclasses, and workshops at institutions and festivals worldwide, and performs as a soloist in a wide variety of performance settings.

Throughout his career, Mr. Damoulakis has performed and recorded as a guest artist, including engagements with the New York Philharmonic, Atlanta Symphony, Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Houston Symphony, Sarasota Orchestra, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic. He performed and recorded with the National Brass Ensemble at Skywalker Ranch and Orchestra Hall in Chicago in 2015. An active chamber musician, he plays regularly with the Strings Music Festival, ChamberFest Cleveland, and the Sun Valley Summer Symphony “In Focus” Series, where he also serves as principal percussionist. He has performed with Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, Gilmore Festival, New Music Consort, and the Pulse Percussion Ensemble. In addition, he is a founding member of the Time Table Percussion Quartet. As a teacher, he has students holding positions in major symphony orchestras throughout the world.

Prior to coming to Cleveland, Mr. Damoulakis lived and worked in New York, where he performed and recorded with the New York Philharmonic (2003-2006), served as principal timpani of the Long Island Philharmonic (1998-2006), and held the position of assistant principal percussion of the Harrisburg Symphony Orchestra (2003-2006). He also performed as an active freelancer in New York, including in the orchestra for Phantom of the Opera on Broadway.

A native of Boston, Massachusetts, Marc Damoulakis holds a bachelor’s degree in percussion performance from the Manhattan School of Music. He continued his studies for four years with the New World Symphony.

Marc and his wife, Samantha, reside in Cleveland Heights.