The Cleveland Orchestra

BROADCAST PRESENTATION

2020-21 Season

S1.E11 In Focus Season 1, Episode 11

_____________________

Order & Disorder

Broadcast Premiere Date/Time:

Thursday, May 20, 2021, at 7 p.m.

filmed April 14 and March 18-19

at Severance Hall, Cleveland

WOLFGANG AMADÈ MOZART (1756-1791)

Clarinet Quintet in A major, K.581

with

Afendi Yusuf, clarinet

Stephen Rose, violin

Jeanne Preucil Rose, violin

Lynne Ramsey, viola

Mark Kosower, cello

1. Allegro

2. Larghetto

3. Menuetto — Trio I — Menuetto

— Trio II — Menuetto

4. Allegretto con variazioni

________________________________________

The Cleveland Orchestra

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

ALBAN BERG (1885-1935)

Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

II. Andante amoros

III. Allegro misterioso — Trio estatico

IV. Adagio appassionato

In addition to the concert performances, each episode of In Focus includes behind-the-scenes interviews and features about the music and musicmaking.

Each In Focus broadcast presentation is available for viewing for three months from its premiere.

_____________________

With thanks to these funding partners:

Presenting Sponsor:

The J.M. Smucker Company

Digital & Seasons Sponsors:

Ohio CAT

Jones Day Foundation

The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company

Medical Mutual

In Focus Digital Partners:

Cleveland Clinic

The Dr. M.Lee Pearce Foundation, Inc.

Leadership Partner:

CIBC

_____________________

This episode of In Focus is dedicated

to the following donors in recognition for their

extraordinary support of The Cleveland Orchestra:

Mr. Richard J. Bogomolny

and Ms. Patricia M. Kozerefski

Dr. and Mrs. Hiroyuki Fujita

JoAnn and Robert Glick

Toby Devan Lewis

Ms. Nancy W. McCann

Mr. Stephen McHale

Mr. and Mrs. Alfred M. Rankin, Jr.

Charles and Ilana Horowitz Ratner

Barbara S. Robinson

O N O F F E R : a program of juxtaposition from two of music’s most creative composers, writing in two styles more than a century apart.

First comes a poignant quintet, written by Mozart in 1789 — a difficult and unhappy year for him — yet filled with sweet and warm music that brings comfort, fresh perspective, and hope. Here is Mozart bringing order to, and despite his disordered life, through music. For this In Focus performance, principal clarinet Afendi Yusuf joins Cleveland Orchestra colleagues in this extraordinary work.

For Alban Berg, writing more than a century after Mozart, the process of musical creation was an intensely-driven search for innovative answers using old materials in new ways — to shake up the old order into newly disordered beauty. In his Three Pieces from Lyric Suite, he creates solace and splendor in contrasting string voices, buzzing and interacting with hard-edged vitality, passionate ardor, and poetic grace.

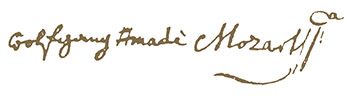

M O Z A R T was baptized as Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus

Mozart. His first two baptismal names, Johannes Chrysostomus, represent his saints’ names, following the custom of the Roman Catholic Church at the time.

In practice, his family called him Wolfgang. Theophilus comes from Greek and

can be rendered as “lover of God” or “loved by God.” Amadeus is a Latin version

of this same name. Mozart most often signed his name as “Wolfgang Amadè Mozart,” saving Amadeus only as an occasional joke. At the time of his death, scholars in all fields of learning were quite enamored of Latin naming and conventions (this is the period of the classification and cataloging of life on earth into king-dom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species, etc.) and successfully “changed” his name to Amadeus. Only in recent years have we started remembering the Amadè middle name he actually preferred.

—Eric Sellen