The Cleveland Orchestra

CONCERT PRESENTATION

Blossom Music Center

1145 West Steels Corners Road

Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio 44223

_____________________

Tchaikovsky's Fourth

Sunday, August 15, 2021, at 7 p.m.

The Cleveland Orchestra

Karina Canellakis, conductor

Behzod Abduraimov, piano

Michael Sachs, trumpet

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841-1904)

The Wood Dove, Opus 110

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975)

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Opus 35

(for solo piano, trumpet, and string orchestra)

1. Allegretto — Allegro vivace — Allegretto

— Allegro — Moderato —

2. Lento —

3. Moderato —

4. Allegro con brio

I N T E R M I S S I O N

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Opus 36

1. Andante sostenuto — Moderato con anima

2. Andantino in modo di canzona

3. Scherzo: Pizzicato ostinato

4. Finale: Allegro con fuoco

Please turn your phone to silent

mode during the performance.

_____________________

2021 Blossom Music Festival

Presenting Sponsor:

The J.M. Smucker Company

This concert is dedicated to

the following donors in recognition

for their extraordinary support

of The Cleveland Orchestra:

Mr. and Mrs. Alex Machaskee

Astri Seidenfeld

Bill and Jacky Thornton

“F O R T H E F I R S T T I M E in my life I have attempted to put my musical thoughts and forms into words and phrases,” Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote to his benefactor Nadezhda von Meck on March 1, 1878. The composer recounted in dire terms how he toiled away on his Fourth Symphony, pouring his soul into lush music.

“I was horribly out of spirits all the time I was composing this symphony last winter,” he continued, “and this was a true echo of my feelings at the time. But only an echo. How is it possible to reproduce it in clear and definite language?”

How is it possible to imbue music with feeling, reproducing the agony, remorse, humor, and joy of human experience? This evening’s concert, featuring conductor Karina Canellakis in her Cleveland Orchestra debut, brings together three distinct and affecting responses from a trio of composers adept at stirring and strumming the heartstrings.

Late in his career, Antonìn Dvořák became enamored with the most expressive of musical forms, the symphonic poem. Inspired by the romantic folktales Karel Jaromír Erben, he started writing a series of emotive one-movement symphonic works. Premiered in 1898, his fourth such work — and the first piece on tonight’s program — The Wood Dove, delves into the anguish of a woman, who kills her husband, falls in love again, but becomes racked by guilt when a wood dove reminds her of her misdeeds.

Shostakovich infamously encoded his music with the discomfit he felt toward Stalin and the Soviet apparatchik of the mid-20th century. But his Piano Concerto No. 1, written in 1933, comes before all that and finds the composer full of humor and youthful bravado. His music has not yet been condemned in the Soviet mouthpiece Pravda. Careful listeners will find quotes of Haydn, Beethoven and Shostakovich’s own works, cleverly embedded throughout. Pianist Bezhod Abduraimov joins The Cleveland Orchestra and principal trumpet Michael Sachs for what the composer called a “heroic, spirited, and joyful” concerto.

This emotional rollercoaster of an evening, comes to an impassioned close with Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony, premiered in 1878. In this piece the composer lays out a landscape at first filled with the looming and oppressive weight of fate. He illustrates the yearning of the past with fleeting glimpses of memories from brighter days. Those darkened skies eventually melt away with comforts of companionship, and turn into a rousing affirmation of communal celebration. As we all come together for a bucolic evening of music, Tchaikovsky’s words provide a fitting proposal: “Why not rejoice through the joys of others? One can live that way, after all.”

—Amanda Angel and Eric Sellen

THE WOOD DOVE [Holoubek], Opus 110

by Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Composed: 1896

Premiered: March 20, 1898, in Brno (in what is today the Czech Republic) conducted by Leoš Janáček

Duration: nearly 20 minutes

_______________________________

A F T E R C O M P L E T I N G his Ninth Symphony, nicknamed “From the New World,” in 1893, Dvořák composed no more symphonies. In the last ten years of his life, he turned his attention instead toward opera, writing three over that period of time, as well as symphonic poems, of which he wrote five from 1896 to 1897.

It is somewhat surprising that Dvořák had not written symphonic poems before. Franz Liszt had realized the potential of the genre forty years earlier, compressing the expressive range of a symphony into a single movement and stuffing it full with romantic ideas and sounds . French and Russian composers wrote symphonic poems in abundance, and in Bohemia both Smetana and Zdeněk Fibich had contributed a number of works to the form, including Smetana’s strongly nationalist cycle of six symphonic poems, Má Vlast [My Homeland], completed in 1880.

The first four symphonic poems Dvořák embarked on, including The Wood Dove, were based on narrative folk-ballads by the Czech poet Karel Jaromír Erben (1811-70). By this time, Richard Strauss had created a sensation with such pieces as Don Juan and Till Eulenspiegel, both with vivid action depicted in orchestral language. Dvořák was also intending to create pieces with a story depicted in the music, and it is possible that he intended a set of six symphonic poems based on Czech folk stories to match Smetana’s half dozen.

The first three Erben-inspired symphonic poems were sketched in rapid succession between January 6 and 22, 1896, and the fourth, The Wood Dove, followed in October and November of the same year.

The Erben stories are graphic and sometimes gruesome tales of kings, princesses, magic castles, and golden rings. At times Dvořák set Erben’s lines to music and then simply removed the words. In other parts, he represented the narrative purely through his music. For The Wood Dove he employed the latter technique,

The story of The Wood Dove concerns a young widow who sorrowfully follows her husband’s coffin to the grave. She then meets a young man who distracts her from her grief. They are married, but when she hears a wood dove cooing in an oak tree above her husband’s grave, she is smitten with remorse and drowns herself. Erben reveals at the end that she had poisoned her first husband.

Most of Dvořák’s musical themes in The Wood Dove have a similar outline, rising a few notes and then falling, so the five episodes are represented in the work primarily through the tempo changes in the score.

The opening represents the husband’s funeral. Soon after the trumpet enters, we hear the widow’s crocodile tears in the flutes and violins. The young man is announced by a distant trumpet, and their wedding is a boisterous scherzo with strong hints of the composer’s popular Slavonic Dances. The festivities over, the couple are alone (strings) when the wood dove can be heard (flutes, oboe, and high harp), answered by a sinister bass clarinet. Driven to distraction by her conscience, the new bride drowns herself. An epilogue portrays a second funeral march, watched over by the now satisfied wood dove.

The Wood Dove was first performed under the direction of Leoš Janáček, who had asked Dvořák if he had a new piece that his orchestra in Brno could play. The premiere was swiftly followed by performances abroad — conducted by Mahler in Vienna, Oskar Nedbal in Berlin, Henry Wood in London, and Theodore Thomas in New York.

—program note by Hugh Macdonald © 2021

________________________________

SCORING: 2 flutes plus piccolo, 2 oboes plus english horn, 2 clarinets plus bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tambourine, bass drum), harp, and strings

CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA TIMELINE: The Cleveland Orchestra has performed this tone poem on only one previous set of concerts, as part of a weekend in May 2016 led by Franz Welser-Möst.

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 in C minor, Opus 35

by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Composed: 1933

Premiered: October 15, 1933, with the Leningrad Philharmonic under the direction of Fritz Stiedry

Duration: about 20 minutes; the four movements are played “attaca” (without breaks or pauses)

______________________

S H O S T A K O V I C H C O M P L E T E D his second opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, at the end of 1932. Ready for a change of direction, he immediately embarked on twenty-four preludes for solo piano, a series of short pieces that allowed him to impose a variety of styles on an essentially Bach-like frame. The revolutionary spirit of the 1920s was still strong and the fatal effects of Stalin’s grip on power (and life) in the Soviet Union had not affected the arts too severely. And Shostakovich was not yet displaying the sullen exterior that would allow him — when his livelihood, even his life, was threatened by the regime — to conceal his real feelings as he channelled them privately into his music.

The extroverted character of the First Piano Concerto, which followed right after the composition of the Twenty-Four Preludes, is free of the dissembling and mystery that envelops the composer’s later music. This was partly because Shostakovich, an introvert in real life, was a young, brilliant pianist who was not shy to play in public. He gave the first performance of the Preludes while still at work on the concerto, and then followed with the premiere of this new piano concerto in the autumn of 1933. It was an immediate success, and he performed it often in the following years. Twenty years later, he added a Second Piano Concerto, which he also played himself, although it was written for, and first performed by, his son, Maxim.

There is some evidence — and even comments by Shostakovich — that suggests the First Piano Concerto was initially planned as a trumpet concerto in a somewhat neo-Baroque style. The trumpet is, indeed, unusually coupled with the strings in the accompanying group. The finished piece, however, does little to support such an origin, with the trumpet’s part so secondary to that of the piano and so neatly complementary to the soloist’s part. (The composer changed his early title for the piece, “Concerto for Piano with the Accompaniment of String Orchestra and Trumpet,” to the straightforward and traditional Piano Concerto.) Certainly one motive for featuring a trumpet was Shostakovich’s admiration for Alexander Schmidt, the principal trumpet in the Leningrad Philharmonic, who played in the first performance with the composer.

Musically, the concerto has provided a happy hunting ground for those who like to spot quotations and allusions, of which it is full. Shostakovich slyly slipped in tunes from the classics as well as from his own works, some of which are difficult to spot even for those who know his music well. A sense of parody reinforces the high-spirited tone of the first and last movements. Snippets of Haydn and Beethoven appear, as well as citations from his own recent works and popular songs.

It is not all fun, however. The slow movement is profoundly reflective, only introducing the trumpet when it is time for the opening tune, originally heard in the violins, to be repeated. Yet there is still space for the piano to take over the closing section of the movement with a new theme.

The third movement is largely subdued, too, being more of an introduction to the finale than a movement in its own right. The severe spirit of Bach is present at many points throughout the concerto, yet it is the exuberance of the first movement, and especially of the fourth-movement finale, that leaves the strongest impression — and gives listeners full satisfaction from this concerto for piano and strings . . . and trumpet.

—program note by Hugh Macdonald © 2021

________________________________

SCORING: string orchestra, plus solo piano and featured trumpet.

CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA TIMELINE: The Cleveland Orchestra first performed this work in November 1936, when music director Artur Rodzinski conducted and Eugene List was the piano soloist with principal trumpet Louis Davidson playing the featured brass role. It has been programmed on only four occasions since then, in 1964, 1978, 2003, and most recently March 2015 when Jahja Ling led a weekend of concerts featuring Daniil Trifonov as the solo pianist along with principal trumpet Michael Sachs.

SYMPHONY NO. 4 in F minor, Opus 36

by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Composed: 1877-1878

Premiered: February 22, 1878, in Moscow

Duration: about 40 minutes

______________________________________________

F E W W O R K S in the orchestral repertoire carry such a strong emotional charge as Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. The capacity of this music to move us to the depths is by design. Tchaikovsky admitted as much.

“There is not a note in this symphony,” he wrote, “. . . which I did not feel deeply, and which did not serve as an echo of sincere impulses within my soul.”

To his patroness Nadezhda von Meck, with whom he kept up a close correspondence for over fourteen years, only ever meeting twice (both briefly, and by accident), he explained the program of the Fourth Symphony in great detail. According to his first-hand analysis (read Tchaikovsky's own words about the symphony in the "Tchaikovsky On Symphony No. 4" tab elsewhere on this digital program book), the gloomier parts of the work are concerned with fate (represented in the opening passage for brass) and depression, and the eternal struggle to rise above it. There are some brighter moments, and the finale supposedly presents a shared joy of community, a cure for the self-hatred and despair that otherwise invades the soul.

It can be argued (and many have) as to whether Tchaikovsky intended for Madame von Meck (or us) to take this program literally. Certainly we should not assume that the symphony is merely a record of the emotional and psychological crisis that he suffered at the time of its composition. The year 1877 brought the composer to a point where suicide was at least a possibility, and he was filled with agitated emotions, which doubtless are reflected in the symphony’s music. But the process of creating art is not a simple translation of life into another medium — a transformation occurs in the creative mind. How specifically the music mirrors actual events is not easy to determine. Nor do we need to know in order to enjoy this musical masterpiece.

In the summer of 1876, Tchaikovsky declared his determination to get married, without anyone in particular in mind as his partner. That winter, he started work on the Fourth Symphony, completing the draft of the first three movements before he met the young lady who was to become his wife. The bizarre circumstances of their meeting, their almost immediate marriage, and the composer’s appalling realization that instead of curing him of his homosexuality as he perhaps hoped, marriage turned out to be a hell even worse than Dante’s version, which he had so recently depicted with great vividness in his musical tone poem Francesca da Rimini.

Tchaikovsky fled, first to his relatives in the Russian countryside, then to Switzerland and Italy, where he completed the symphony and finished the orchestration. Tchaikovsky’s muse never let up. Not only did he complete the Fourth Symphony at this time, he also composed his finest opera, Eugene Onegin, and the exquisite Violin Concerto soon after. There were occasional fallow periods in his career, but the year 1877, however dramatic in domestic affairs, was not one of them. To the end of his life, he sustained the habit of composing for several hours every day, producing one of the most varied and appealing bodies of work of any composer of his generation.

THE MUSIC

At the very start of the Fourth Symphony’s first movement, the forthright statement of horns and bassoons grabs the listener’s attention. We are not likely to overlook its recurrence at critical points in this and later movements — and we are not supposed to. But the music settles into a plaintive flow in a halting triple rhythm, overwhelmingly committed to the minor key. The first movement offers some striking contrasts of mood and key, such as the clarinet’s gentle waltz-tune with playful responses from the other winds and a swaying figure in the violins accompanied by a pair of drums. But the main theme returns, and the symphonic argument leads to the first of many stupendous climaxes in this work.

The second movement is not a profound moment of soul-searching, but a tender intermezzo featuring the solo oboe (later other winds), very lightly accompanied. There is a strong Russian flavor in this movement and no smiles.

The mood lightens in the scherzo third movement, one of Tchaikovsky’s neatest inventions. The conventional division of orchestras into the three families of strings, woodwinds, and brass gave him the idea of featuring each in turn, each with its own melody, its own tempo, and its own character. The strings, furthermore, are plucked throughout, the entire movement calling for pizzicato. The divisions are not watertight, the themes keep intruding on the others. The impression is of a teasing game, full of humor and free from dark thoughts of any kind.

The noisy finale fourth movement features in its midst a Russian folksong based on a descending minor scale answered (sometimes) by two solid thumps. In due course, the solemn main theme makes its dramatic appearance, but it cannot stem the tide of high spirits that close the symphony, leaving Tchaikovsky’s depression far behind.

—program note by Hugh Macdonald © 2021

________________________________

SCORED FOR: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, triangle), and strings

CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA TIMELINE: The Orchestra's history with Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 4 dates back to its very first concert on December 11, 1918, at Grays Armory when Nikolai Sokoloff inaugurated the new ensemble in the second and final movements. He eventually led the full work in 1921. It has been a staple ever since. The Orchestra most recently performed it with Jajha Ling during the 2019 Blossom Music Festival.

T C H A I K O V S K Y W R O T E a letter on March 1, 1878, to his patroness and benefactor Nadezhda von Meck, to whom he dedicated the published score of the Fourth Symphony. In the letter, he tried to describe what he referred to as “our symphony,” movement by movement, with musical examples of the work’s major themes. The underlying emotional landscape that he felt the music expressed provides an interesting view of his creative frame of reference for this symphony:

My Dearest Friend . . .

In our symphony there is a programme (that is, the possibility of explaining in words what it seeks to express), and to you and you alone I can and wish to indicate the meaning both of the work as a whole, and of its individual parts. Of course, I can do this here only in general terms.

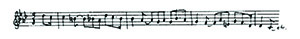

The introduction is the kernel of the whole symphony, without question its main idea:

This is Fate, the force of destiny, which ever prevents our pursuit of happiness from reaching its goal, which jealously stands watch lest our peace and well-being be full and cloudless . . . and constantly, ceaselessly poisons our souls. It is invincible, inescapable. One can only resign oneself and lament fruitlessly:

The disconsolate and despairing feeling grows ever stronger and more intense. Would it not be better to turn away from reality and immerse oneself in dreams?

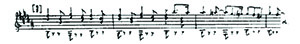

O joy! A sweet, tender dream has appeared. A bright, beneficent human form flits by and beckons us on:

How wonderful! How distant now is the sound of the implacable first theme! Dreams little by little have taken over the soul. All that is dark and bleak is forgotten. There it is, there it is — happiness!But no! These were only dreams, and Fate awakens us.

And thus, all life is the ceaseless alternation of bitter reality with evanescent visions and dreamed-of happiness. . . . There is no refuge. We are buffeted about by this sea until it seizes us and pulls us down to the bottom. There you have roughly the program of the first movement.The second movement of the symphony expresses a different aspect of sorrow, that melancholy feeling that arises in the evening as you sit alone, worn out from your labors. You’ve picked up a book, but it has fallen from your hands. A whole procession of memories goes by. And we are sad that so much already is over and gone, and at the same time we remember our youth with pleasure. We are weary of life. How pleasant to relax and look back. Much comes to mind! There were blissful moments, when our young blood seethed and life was good. And there were bitter moments of irretrievable loss. It is at once sad and somehow sweet to lose ourselves in the past . . .

The third movement does not express definite feelings. These are, rather, capricious arabesques, fugitive images that pass through one’s mind when one has had a little wine to drink and is feeling the first effects of intoxication. At heart one is neither merry nor sad. One’s mind is a blank. The imagination has free rein and it has come up with these strange and inexplicable designs.

. . . Among them all at once you recognize a tipsy peasant and a street song. . . . Then somewhere in the distance a military parade goes by. These are . . . images that pass through one’s head as one is about to fall asleep. They have nothing in common with reality; they are strange, wild and incoherent . . .

The fourth movement. If you can find no impulse for joy within yourself, look at others. Go out among the people. See how well they know how to rejoice and give themselves up utterly to glad feelings. But hardly have you succeeded in forgetting yourself and enjoying the spectacle of others’ joys, when tireless Fate reappears and insinuates itself. But the others pay no heed. They do not even look around to see you standing there, lonely and depressed. Oh, how merry they are! And how fortunate, that all their feelings are direct and simple. Never say that all the world is sad. You have only yourself to blame. There are joys, strong though simple. Why not rejoice through the joys of others? One can live that way, after all.

. . . Just as I was putting my letter into the envelope I began to read it again, and to feel misgivings as to the confused and incomplete programme that I am sending you. For the first time in my life I have attempted to put my musical thoughts and forms into words and phrases. I have not been very successful. I was horribly out of spirits all the time I was composing this symphony last winter, and this was a true echo of my feelings at the time. But only an echo. How is it possible to reproduce it in clear and definite language? I do not know. I have already forgotten a good deal. Only the general impression of my passionate and sorrowful experiences has remained.

Yours, with devotion and respect, Pyotr

I N T E R N A T I O N A L L Y A C C L A I M E D for her emotionally charged performances, technical command, and interpretive depth, Karina Canellakis regularly appears with top orchestras in North America, Europe, United Kingdom, and Australia. She is the chief conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, and holds the title of principal guest conductor with both the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin. She makes her Cleveland Orchestra debut at Blossom Music Festival with this evening's concert.

Other upcoming debuts include the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, and San Francisco Symphony. In Europe, she debuts with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, and Orchestre National de France at Festival de Saint-Denis, followed by a fully staged production of Eugene Onegin at Théâtre des Champs-Elysée.

On the operatic stage, Ms. Canellakis has conducted Die Zauberflöte and a fully staged production of Verdi’s Requiem with the Zurich Opera, Don Giovanni and Le nozze di Figaro with Curtis Opera Theatre, and gave the world premiere of David Lang’s opera The Loser at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. She led Peter Maxwell Davies’s final opera, The Hogboon, with the Luxembourg Philharmonic.

Since winning the Georg Solti Conducting Award in 2016, Ms. Canellakis has worked with leading orchestras around the world, including the Philadelphia Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Toronto Symphony, London Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique du Radio France, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Oslo Philharmonic, and the Melbourne and Sydney symphony orchestras.

Already known to many in the classical music world for her virtuoso violin playing, Ms. Canellakis was initially encouraged to pursue conducting by Simon Rattle during the two years she played regularly in the Berlin Philharmonic’s Orchester-Akademie. She plays a 1782 Mantegazza violin on loan from a private patron.

P I A N I S T B E H Z O D A B D U R A I M O V made his debut with The Cleveland Orchestra at the 2017 Blossom Music Festival. He has also appeared with the Philharmonia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, San Francisco Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, and Concertgebouw with conductors including Valery Gergiev, Lorenzo Viotti, James Gaffigan, Jakub Hrůša, Santtu-Matias Rouvali, and Gustavo Dudamel.

In 2020 Abduraimov saw the release of two recordings: Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra under James Gaffigan for which he performed on Rachmaninov’s own piano from Villa Senar, and Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No.3 with the Concertgebouw under Valery Gergiev.

He was the grand prize winner of the 2009 London International Piano Competition and, the following year, won the Kissinger KlavierOlymp. Born in 1990 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Abduraimov began to play piano at the age of five as a pupil of Tamara Popovich at the Uspensky State Central Lyceum in his hometown. He is a graduate of Park University’s International Center for Music, where he studied with Stanislav Ioudenitch, and now serves as the institution’s artist-in-residence.

_______________________

Piano by Steinway & Sons.

Principal Trumpet

Robert and Eunice Podis Weiskopf Endowed Chair

The Cleveland Orchestra

Principal Cornet

Mary Elizabeth and G. Robert Klein Endowed Chair

The Cleveland Orchestra

Michael Sachs joined The Cleveland Orchestra as principal trumpet in 1988. His many performances as soloist with the Orchestra include the world premieres of trumpet concertos by John Williams and Michael Hersch (both commissioned by the Orchestra for Mr. Sachs), the United States and New York premieres of Hans Werner Henze’s Requiem, and, most recently, the world premiere of Matthias Pintscher’s Chute d’Étoiles.

Mr. Sachs serves as head of the trumpet department at the Cleveland Institute of Music and is a member of the faculty at Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music. In addition to teaching with leading summer festivals and, since 2015, as music director of Strings Music Festival in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, he presents masterclasses and workshops at conservatories and universities throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia as a clinician for Conn-Selmer instruments.

Michael Sachs holds a bachelor’s degree in history from UCLA, with additional studies at New York’s Juilliard School. For more information, please visit www.michaelsachs.com.

A print-friendly PDF of this

concert's program book information

can be found at the following link:

AUG 15 - TCHAIKOVSKY FOURTH