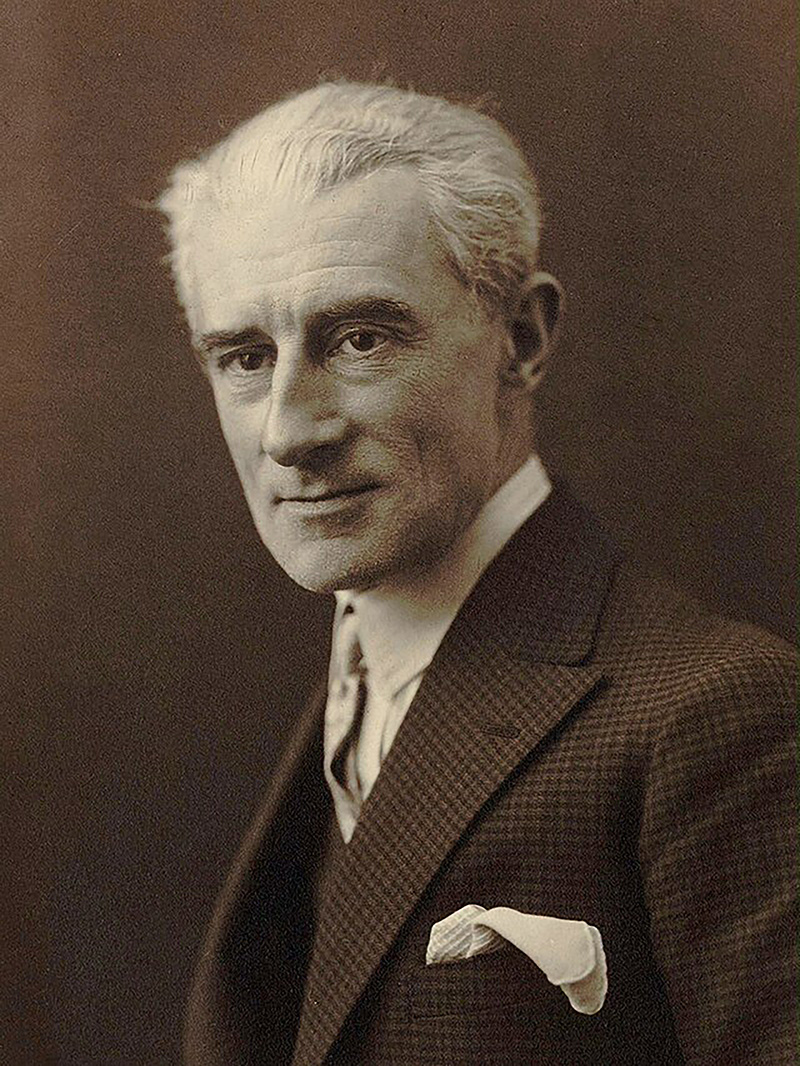

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, Ciboure, Basses-Pyrénées, France

Died: December 28, 1937, Paris

Boléro

- Work Composed: 1928

- Premiere: November 22, 1928, Paris, at the Paris Opéra (staged ballet); Ida Rubenstein’s ballet troupe, Walther Straram conducting, choreography by Bronislava Nijinska. Ravel conducted the first concert performance with the Lamoureux Orchestra in Paris on January 11, 1930, but the North American premiere took place two months earlier on November 14, 1929 in New York, Arturo Toscanini conducting the New York Philharmonic.

- Duration: approx. 8 minutes

First conceived as a ballet for Ida Rubinstein’s dance company in Paris, Bolero is a single orchestral crescendo repeating the same melody and the same rhythm over and over again. It is a bold experiment that, in another composer’s hands, could have turned out tedious in the extreme, yet Ravel made it exciting thanks to a colorful orchestration and an irresistible, and highly challenging, snare-drum part.

“Orchestral Tissue Without Music”

Ravel once described Bolero as “seventeen minutes of orchestral tissue without music.” Somewhat to the composer’s surprise, Bolero eclipsed most of his other works in popularity. Ravel himself considered it “an experiment in a very special and limited direction that should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything different from, or anything more than, it actually does achieve.”

Interestingly, the original title of the piece was Fandango, another Spanish dance, which has a much slower tempo. Ravel always insisted that the tempo of his piece should not be rushed, and had a major, and much-publicized controversy with Arturo Toscanini on this very point. The original ballet’s storyline, if it may be called that, is as follows:

The curtain rises on a dark, smoky room in a Spanish tavern. A woman enters, dressed as a gypsy, with a tall Spanish comb and a scarlet and black shawl. Atop a table, she begins to stamp out the rhythm of the bolero. Instantly the room fills with men. The music grows in passion and the woman is joined in the dance, first by one and then by a dozen or so men. The excitement increases. Knives are drawn. A fight is barely avoided. The gypsy woman is tossed from arm to arm. Then, suddenly, all comes to a stop as the music reaches its climax. Curtain.

A Single Long Crescendo

Bolero is a single long-drawn-out crescendo in which the instruments of the orchestra enter gradually to build up the final climax. The melody, which is quite complex, with many irregularities in its phrase structure, never changes. More precisely, it alternates between two forms, one beginning with the note C, the other with B-flat. Generally, we hear the “C” version twice, followed by two renditions of the “B-flat” version, and then the “C” form again. The snare drums play the bolero rhythm without a moment’s interruption from beginning to end. The bass part is not exceedingly varied either: it consists of only two notes, C and G, for about 16-1/2 minutes out of 17. It therefore comes as a great surprise when, just before the end, the bass suddenly changes from C–G to E–B for exactly eight measures. C and G then return to close the piece.

— Peter Laki