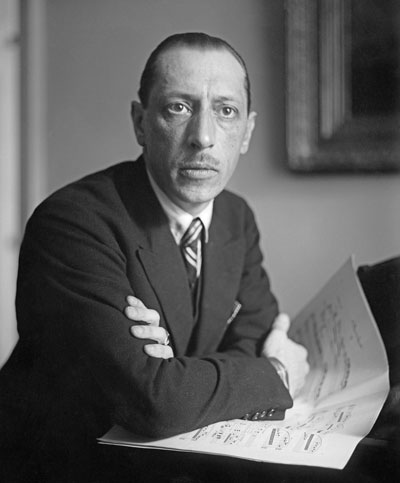

George Gershwin

Born: September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, New York

Died: July 11, 1937, Los Angeles, California

Concerto in F

- Composed: November 1925

- Premiere: December 3, 1925 at Carnegie Hall, New York City, Walter Damrosch conducting the New York Symphony with George Gershwin, piano

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: March 1927, Fritz Reiner, conductor; George Gershwin, piano.

- Most Recent: April 2018, Cristian Măcelaru conducting; Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano. CSO Recording: Gershwin: Concerto in F released in 1953, Thor Johnson conducting; Alec Templeton, piano.

- Notable: this work was performed as part of the 1966 World Tour, Max Rudolf conducting; Lorin Hollander, piano.

- Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, whip, wood block, xylophone, strings

- Duration: approx. 31 minutes

Between the First and Second World Wars, global societies grappled with an array of reckonings, including over the directions their cultures were heading. Uneasy relationships between “high” and “low” were negotiated, with flapper-era critics even inaugurating a fraught new category of the “middlebrow,” betwixt and between, as Virginia Woolf described this murky cultural space. Among new hybrid possibilities composers explored was the fusion of classical idioms with jazz, what Gunther Schuller later called a musical “third stream.” Embedded deeply in the fray of this historical discourse was George Gershwin. Having established himself as a tune plugger and songwriter for comic theater and publishing houses after leaving high school, Gershwin found his footing in concert music by swimming this “third stream.” He did so amid the increasing industrialization of the 1920s and 30s, where jazz often indexed burgeoning modernisms. Most famously, in 1924, he found this voice in the loved, lauded and lucrative Rhapsody in Blue for piano and orchestra.

In April 1925, Walter Damrosch — who admired the Rhapsody — commissioned a “New York Concerto” from Gershwin for the New York Symphony Society. The premiere of what became the Concerto in F occurred at Carnegie Hall on December 3, 1925, with the composer as soloist. As one critic relayed: “A crowd of almost Paderewskian proportions sloshed in out of the deluge to witness Mr. Gershwin’s nuptials with the symphonic Muse.” Gershwin regularly performed the Concerto as soloist, including in March 1927 with Fritz Reiner leading the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in its first performance of the piece.

All told, Gershwin wrote four works for solo piano and orchestra: Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F led to the Second Rhapsody (1932) and “I Got Rhythm” Variations (1934). For Gershwin, this partly constituted a deeper exploration of “serious” music, including the early opera Blue Monday Blues (1922), and, later, An American in Paris (1928) and Porgy and Bess (1935)—all representative of Gershwin’s “hybrid” style.

For Gershwin, the Concerto was a proving ground. His sister, Frances Gershwin Godowsky, noted the Concerto was “one of his most mature works and shows his musical development.” Gershwin regularly combatted accusations that Rhapsody in Blue was a “happy accident” by an unserious song composer. Perceptions of Gershwin’s limitations fomented, possibly stemming from his self-education, his lack of an internationally renowned composition teacher or his popularity. Some bemoaned that Ferde Grofé orchestrated Rhapsody for the 1924 Paul Whiteman Orchestra’s premiere in New York’s Aeolian Hall. Gershwin’s occasional self-deprecation about his craft may not have helped, either. Yet, he composed and orchestrated the Concerto in F alone, drafting its themes in Europe during spring 1925 before returning to America and finishing composition in September and orchestration in November. Defending his reputation, Gershwin wrote, “I went out, for one thing, to show them that there was plenty more where that had come from. I made up my mind to do a piece of absolute music…. The Concerto would be unrelated to any program.”

Despite neutralizing the title, programmatic attachments have been difficult for the composer to escape. Critics have long read narratives into the piece, including one who praised it as “the most startlingly evocative ‘New York’ music ever written.” The piece has even been choreographed for ballet more than once, evidence of its narrative potential. Whether it invokes any specific imagery, the Concerto has enthralled listeners with an evocative, emulsified sound world unique to its composer.

The first movement opens in unusual fashion with solo timpani. The gesture may be best known from Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, but Gershwin rebuffs Beethoven’s reticent tenderness, instead sounding a clarion call in accented forte notes. After the opening salvo, the work ignites with the rhythm of James P. Johnson’s famous 1923 song “The Charleston.” The Concerto’s first distinctive theme soon enters, an arching five-tone melody in dotted rhythms played by solo bassoon that will frequently resurface. In contrast, the piano soloist’s first entry introduces the movement’s second theme, a halting melody with repeated offbeat notes that strives upward but just as often dips down. No theme is extensively developed, Gershwin instead opting for a fragmentary “tunes into themes” approach that also underpins the Rhapsody and An American in Paris. Gershwin then explores the orchestra’s colors, building a richly dark chamber ensemble led by English horn doubled by viola for a countermelody. These timbres foreshadow the movement’s interior cantabile section where Mahlerian tunefulness matches with adroit orchestral partitioning. Following the lyrical section, the piano re-energizes, summoning the movement’s final recapitulatory tapestry of thematic counterpoint and pianistic technique.

For many, the second movement is the Concerto’s jewel. Sounds of chamber music already established, Gershwin brings new degrees of transparency in this middle movement, which he once described as exhibiting Mozartian simplicity. The texture lends well to a blues-influenced style, a tradition typically involving smaller ensembles or a single self-accompanying singer. The movement features a solo trumpet traversing a noticeably wide range, crackling in its upper tessitura and swooning at the lower end, filled between with sinewy “blue” notes. The piano answers with plucky up-tempo music, itself complemented by a more rhythmic orchestral section that hints at the boom-chuck of the foxtrot rhythm. These disparate parts, recurring refrain (the trumpet blues melody) and contrasting episodes resonate within the movement’s traditional rondo form, modeling Gershwin’s self-conscious strategy of innovating within known forms.

The finale’s rhythmic, hammering opening motif initiates another rondo, signaling Gershwin’s further engagement with tradition. Critics have noted the striking resemblance between Gershwin’s refrain and the demonically fast repeated notes of Prokofiev’s Toccata, Op. 11, a lineage stretching back to J.S. Bach, Robert Schumann, Claude Debussy and others. The comparisons are hardly superficial: Gershwin studied, even parodied, these composers. The movement also brings audiences back to the first movement’s later portions, where the soloist must utilize their full technical abilities, and reprises familiar themes from both previous movements.

Nineteenth-century composers similarly worked within established forms to create musical unity, as did Gershwin’s contemporaries and successors, who likewise found this kind of formal logic appealing in the face of seemingly limitless aesthetic possibilities. The Concerto in F thus serves as an inflection point for Gershwin, but also signals a waypoint for addressing 20th century’s tumults.

—Jacques Dupuis