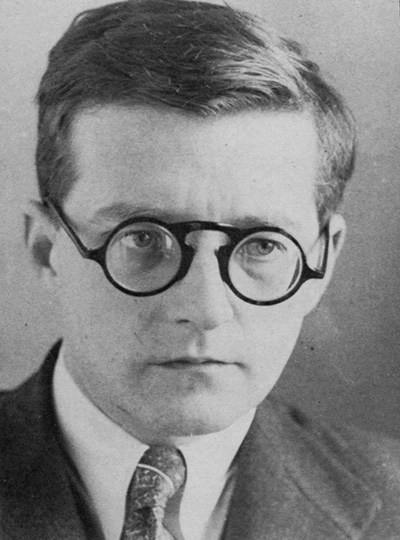

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, St. Petersburg, Russia

Died: August 9, 1975, Moscow

Symphony No. 4 in C Major, Op. 43

- Composed: 1934–36

- Premiere: December 30, 1961, Moscow. Kiril Kondrashin conducting the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra

- CSO Notable Performances: These are the first CSO performances of this work.

- Instrumentation: 4 flutes, 2 piccolos, 4 oboes (incl. English horn), 4 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 tubas, 2 timpani, bass drum, castanets, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, wood block, xylophone, 2 harps, celeste, strings

- Duration: approx. 60 minutes

In February 1935, the Union of Soviet Composers held a three-day conference devoted to sinfonizm — a concept intended to cover many theoretical and ideological issues pertaining to symphony-writing: style, technique, musical meaning, social context, political implications and more. Clearly, in the Soviet Union, you couldn’t have a symphony without ‟symphonism.” In an earlier age, Mahler proclaimed that the symphony should embrace the entire world, but Mahler wrote his symphonies without feeling overly constrained by how the world might react to the embrace. That world was often hostile to Mahler, but he could shrug it off, saying, famously, ‟I can wait.” Soviet composers did not have the same luxury. The world they had to embrace was the real world of their immediate political environment, and the reactions of the powers-that-be could make or break a career.

The 29-year-old Shostakovich had just started working on his Fourth Symphony when he addressed the conference. He was already an international celebrity, catapulted to fame by his First Symphony a decade earlier. In the late 1920s, he had composed two more symphonies — relatively short, propagandistic works with final choruses that drove the political message home. Since 1932 at the latest, the composer had been working on a fourth symphony, conceived on a larger scale than anything he had ever before written.

In his speech, Shostakovich referred to his work-in-progress as his ‟composer’s credo,” announcing that it would confirm his personal style, which he wanted to be ‟simple and expressive.” But he had some thoughts on that personal style that — as he was to find out — didn’t sit well with some of the apparatchiks in the room, for whom every innovation was a sign of Western-influenced “formalism” and had to be rejected:

Striving for simplicity is sometimes understood somewhat superficially: as often as not simplicity becomes feeble imitation. But to express oneself in a simple way does not mean using the language that was in use 50 or a hundred years ago.

Shostakovich was a great admirer of Mahler’s symphonies, then little known in Russia, but championed by Shostakovich’s best friend, the musicologist Ivan Sollertinsky, who wrote a book about the Austrian composer. Mahler’s influence can be felt in the scope of Shostakovich’s work, and in the use of distorted march and dance motifs. There is even an echo of the cuckoo-call, straight from Mahler’s First Symphony.

Yet Shostakovich never fell into ‟feeble imitation.” His musical landscape is as far removed from Mahler’s as can be; there are no nostalgic evocations of the past, and he can take no comfort in moments of high spirituality. The world being embraced here — the only world Shostakovich knew — is an unremittingly bleak place, and no escape from grim realities is possible. The music seems to grope its way through the darkness; a clear sense of direction is only intermittently present.

Any symphony of an hour’s length is a monumental voyage, but the itinerary this time includes many unpredictable detours and a general uncertainty about what the next moment might bring. There are episodes in turn grotesque, tragic and playful; often the same melodic material is used to express opposite emotions, through changing orchestration and dynamics. Shostakovich employs a multiplicity of compositional techniques, from relatively simple melody-and-accompaniment textures to the fierce Presto fugue in the middle of the first movement.

The winding road concludes with an astonishing pair of codas. The first of these, glorious and triumphant, is precisely the kind of ending a Soviet symphony would seem to require. Yet, in this case, the grandiose ending is contradicted, if not entirely destroyed, by a subdued and eerie passage where, over a relentlessly repeated low C note in the harps and contrabasses, a languid farewell melody (a transformation of an earlier theme) unfolds. The final sounds of the celeste and timpani uncannily anticipate the ending of Shostakovich’s 15th and last symphony (1971), which has been generally understood as an image of death.

Shostakovich clearly did not believe that new sounds, or a complex and tragic message, were incompatible with Soviet symphonism. Yet the authorities thought otherwise. The composer wasn’t quite finished with the symphony when, in January 1936, Pravda, the official Communist daily, published its infamous editorial ‟Muddle Instead of Music,” a brutal attack on Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. In those days of the Great Terror, when Stalin had millions of Soviet citizens imprisoned, exiled or executed, such an attack was life-threatening, for Shostakovich could easily have been deported to the Gulag (a system of forced-labor camps). He was spared, but his life was never the same.

Under these circumstances, Shostakovich (who became a father in May 1936) had to think twice whether to release a symphony that would surely add insult to injury in the eyes of the Party officials. In the fall, the Leningrad Philharmonic began preparing the work under Austrian conductor Fritz Stiedry. Shostakovich withdrew the symphony after the 10th rehearsal, claiming that it no longer corresponded to his ‟current creative convictions.” Other purported (and quite unconvincing) reasons, from Stiedry’s alleged incompetence to Shostakovich’s frustration over some technical problems he apparently couldn’t solve, were given by different people at various times, but the truth, no doubt, was what the composer’s close friend Isaak Glikman later revealed. According to Glikman, Shostakovich had been summoned to the office of Comrade Renzin, the director of the Philharmonic. Glikman recalled, ‟Not wanting to resort to administrative measures, [Renzin] had prevailed upon the composer to refuse consent for the symphony’s performance himself.”

The only copy of the orchestral score was lost during World War II. Fortunately, the parts from the 1936 rehearsals survived, and thus Shostakovich was able to reconstruct the symphony, which he first did in a two-piano version in 1946. He gave a private reading of this version with his friend, the composer Mieczysław Weinberg, but it took another 15 years before the symphony was played in public by an orchestra. Eight years after Stalin’s death, on December 30, 1961, the Moscow Philharmonic under the direction of Kirill Kondrashin finally gave the premiere. The overwhelming success of the symphony, both in Russia and abroad, was vindication for Shostakovich, who was at last able to admit openly how he felt about his work. The composer, who at this point had completed no fewer than 12 symphonies, told a friend quite simply that No. 4 was the very best thing he had ever written.

—Peter Laki