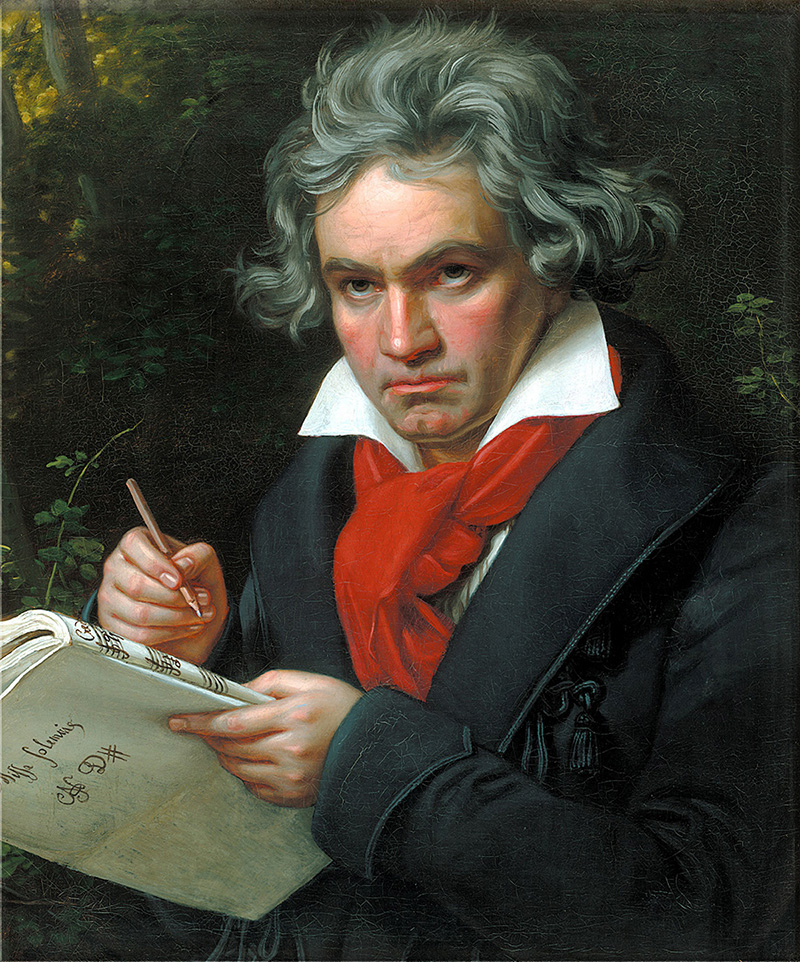

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

String Quartet No. 6 in B-flat Major, Op. 18, No. 6

- Composed: 1800

- Premiered: 1800 in Vienna

“He was short, about 5 feet, 4 inches, thickset and broad, with a massive head, a wildly luxuriant crop of hair, protruding teeth, a small rounded nose, and a habit of spitting whenever the notion took him. He was clumsy, and anything he touched was liable to be upset or broken. Badly coordinated, he could never learn to dance, and more often than not managed to cut himself while shaving. He was sullen and suspicious, touchy as a misanthropic cobra, believed that everybody was out to cheat him, had none of the social graces, was forgetful, and was prone to insensate rages.” Thus the late New York Times critic Harold Schonberg, in his book The Lives of the Great Composers, described Ludwig van Beethoven, the burly peasant with the unquenchable fire of genius who descended, at age 22, upon Vienna in 1792.

In a world still largely accustomed to the reserved, genteel musical style of pre-Revolutionary Classicism, Beethoven burst like a meteor upon the Viennese scene. The Viennese aristocracy took this young lion to its bosom. Beethoven expected as much. Unlike his predecessors, he would not assume the servant’s position traditionally accorded to a musician, refusing, for example, not only to eat in the kitchen, but becoming outspokenly hostile if he was not seated next to the master of the house at table. The more enlightened nobility, to its credit, recognized the genius of this gruff Rhinelander and encouraged his work as pianist and composer, providing much of Beethoven’s support during his early years in Vienna.

The year of he completed the six Op. 18 String Quartets — 1800 — was an important time in Beethoven’s development. He had achieved a success good enough to write to his old friend Franz Wegeler in Bonn, “My compositions bring me in a good deal, and may I say that I am offered more commissions than it is possible for me to carry out. Moreover, for every composition I can count on six or seven publishers and even more, if I want them. People no longer come to an arrangement with me. I state my price, and they pay.” At the time of this gratifying recognition of his talents, however, the first signs of his fateful deafness appeared, and he began the titanic struggle that became one of the gravitational poles of his life. Within two years, driven from the social contact on which he had flourished by the fear of discovery of his malady, he penned the Heiligenstadt Testament, his cri de cœur against that wicked trick of the gods. The Op. 18 String Quartets stand on the brink of that great crisis in Beethoven’s life.

Although the B-flat Quartet was apparently the next-to-last number of Op. 18 to be composed, Beethoven chose to publish it at the end of the set because of its extraordinary finale, subtitled La Malinconia ("melancholy"), which musicologist Joseph Kerman called “an arresting premonition of achievements to come.” As if to serve as a foil for the daring ending of the work, the first two movements, for all their characteristically Beethovenian energy and ingenuity, are conservative in form and idiom. A vigorous, leaping melody in the first violin serves as the main theme of the opening movement. Long ribbons of scales provide the transition to the second theme, an amiable strain of limited range in dotted rhythms. The leaping main theme and the scalar transition motive are explored in the development. A long preparation that finally settles on a quiet, held chord ushers in the recapitulation.

The Adagio, built in a simple three-part form, begins with a suave theme presented by the violin above a sparse accompaniment in the lower strings; the center section is initiated by an attenuated line given in unison by the first violin and cello.

The Scherzo is an elaborate, almost quirky, exploration of the ways in which triple-meter measures can be divided into unusual rhythms and ambiguous groupings through syncopations and cross accents; the tiny trio is occupied by a flippant melody for the violin.

The finale, like a number of movements from the compositions of Beethoven’s last period, is constructed in several continuous but highly contrasted sections. It begins with the slow La Malinconia introduction, almost a movement in itself, which Beethoven instructed to be played “with the greatest delicacy.” So advanced is the harmony of this passage that musicologist Philip Radcliffe suggested that, reworked for orchestra, it would not be out of place in a Wagner opera. Another musicologist, Daniel Gregory Mason, wrote, “These measures carry us into new regions of musical expression. In this strange half-light, this mystical atmosphere of trance and the sense of something unknown impending, we are far indeed from the gay sunlight of 18th-century finales.” The main body of the movement, in rondo form, is fast and cheerful, though the pensive strains of the slow opening return before a furious dash to the end.

© Dr. Richard E. Rodda