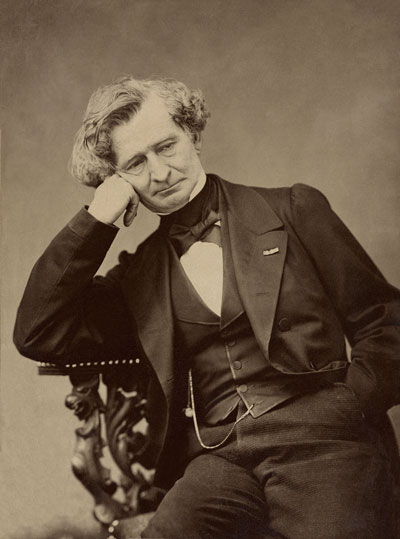

Hector Berlioz

Born: June 15, 1843, in Bergen, Norway

Died: September 4, 1907, in Bergen, Norway

Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14a

- Composed: 1830

- Premiere: December 5, 1830, at the Paris Conservatoire

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: March 1897, Frank Van der Stucken conducting.

- Most Recent: March 2022, Louis Langrée conducting.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes (incl. English horn), 2 clarinets (incl. E-flat clarinet), 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 cornets, 3 trombones, 2 tubas, 2 timpani, 2 bass drums, bells, crash cymbals, snare drum, suspended cymbals, 4 harps, strings

- Duration: approx. 55 minutes

A young man, head over heels in love with a woman he barely knows but has long ogled from afar, imagines their lives together. He loses himself in their shared passion, he dreams of them dancing before a rarefied crowd, he luxuriates in their peregrinations through the countryside. But then the heat suddenly goes out, love turns to hate and he snaps, killing his beloved in cold blood. He is found guilty of murder, sent to the guillotine and finds himself surrounded by witches, imps and other sacrilegious figures. Yet, before dark forces completely overwhelm him, another supernatural force appears to offer aid. The scene ends optimistically, although not necessarily with victory. The protagonist’s fate is unknown.

If Hector Berlioz were alive today, he might have pitched this fantastic tale to Netflix or a Hollywood executive. Indeed, its blend of horror and romance, escapism and obsession, and relatable but still-distant fantasy make for great entertainment today, just as it would have when Berlioz penned it in 1830. However, instead of releasing his “Episode in the Life of the Artist” as a short story or poetic ballade, he presented it as the basis for a five-movement orchestral work that he called Symphonie fantastique. This decision divided Berlioz’s critics, audiences and even fellow artists, and — almost two centuries after its creation — continues to raise questions about music and meaning.

Berlioz had few compositional models when he began work on the piece, so he turned inward for inspiration, drawing on his own life, loves and slim compositional portfolio. The earliest material to make its way into the Symphonie fantastique can be traced to around 1815, when the 12-year-old Berlioz, madly in love with the 18-year-old Estelle Duboeuf, penned an angsty song whose vocal line shaped the “sigh” motives of the violins heard in the opening of the first movement. The relationship — if there even was one — went nowhere, but Berlioz would continue to find creative muses throughout his life, including English actress Harriet Smithson.

Berlioz first saw Smithson on the stage of the Paris Odéon in 1827, where she played Ophelia, and he excitedly returned four days later to see her as Juliet. He later noted in his Mémoirs that he was, “[b]y the third act, scarcely able to breathe — it was as though an iron hand gripped me by the heart — I knew I was lost” — this despite the fact that he hardly knew a word of English. With Smithson completely unaware of Berlioz’s affections (they would not meet until 1832), the Symphonie fantastique thus became a vessel for the composer’s pent-up longing. Indeed, it is no coincidence that the program describes “a young musician, afflicted with that moral disease that a well-known writer [Berlioz was referencing François-René de Chateaubriand] calls the vague des passions,” who falls for an unattainable, ideal woman.

Berlioz’s deep love of literature and the theatre enabled his serendipitous encounter with Smithson, but it also provided important material for many of the “events” that make up the plot of the Symphonie fantastique. As did Part I of Goethe’s Faust, which had appeared in a celebrated French translation by Gérard de Nerval in 1827 that Berlioz admitted he read “incessantly, at meals, at the theatre, in the street, wherever I happened to be.” Berlioz’s Eight Scenes from Faust, for voice and piano, was his first compositional response to Goethe’s play; the fifth movement of the Symphonie fantastique, partially inspired by the play’s Walpurgis Night scene, would be his most celebrated. Berlioz was also likely inspired by Victor Hugo, who was actively challenging the classical orthodoxy of French theatre in works like Cromwell (1827) and Hernani (1830).

Beyond literary luminaries like Shakespeare, Goethe and Hugo, Berlioz also drew on his early schooling in medicine and a general interest in academic psychology and Romantic fantasy. For instance, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1821–22), which appeared in a whacky French translation by Alfred de Musset in 1828, explored drug-induced dreams, fantasies and other workings of the human mind. Berlioz’s reading of it undoubtedly left a mark on the second half of the symphony’s program. Earlier in the century, French psychiatrists Jean-Étienne Esquirol and Étienne-Jean Georget had diagnosed a disease called “monomania,” in which a patient presents an unnatural, protracted fixation on another person or object. Berlioz clearly (and cleverly) adopted their notion of the “idée fixe” to add motivation to the symphony’s protagonist and unification to its storyline.

How all these external elements shaped the music, program and their mutual relationship has been debated since even before the work’s premiere. Having set May 30, 1830, for his symphony’s first performance, Berlioz sought to drum up public interest by sharing its program with the press. One critic held it to be a “bold and bizarre act which is truly striking,” while another characterized it as a “musical novel, for it truly is one, with all the luxuriance of emotion and incident of modern literature.” Unfortunately for Berlioz, these eager critics would have to wait more than six months for the work’s premiere, which finally took place on December 5, 1830, at 2 p.m. in the Grande salle of the Conservatoire.

As the momentous date approached, cautionary voices started weighing in, especially the powerful critic François-Joseph Fétis, who wondered if Berlioz’s need to provide a “truly curious” program proved the inability of music “to paint material facts or express abstractions.” After hearing the work, Fétis concluded that “this music arouses astonishment rather than pleasure.” Berlioz had, in Fétis’ estimation, directed his vast imagination toward the production of superficial effects, such as the colorful ball scene or the dramatic march. Not everyone thought this a waste of Berlioz’s talent, of course, and Berlioz’s orchestral works would strongly influence the music of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner, Russia’s Mighty Handful (composers Balakirev, Cui, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin), and Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

But it would take longer for Berlioz to overcome criticism of his poor handling of form and idea. Fétis’ screed prompted Robert Schumann to pen a celebrated review of the Symphonie fantastique in 1835, but it would not be until around mid-century that a critical mass of proponents came to Berlioz’s aid. Chief among them was Liszt, who posited that “the return, alteration, change and modulation of motives are caused by their relationship to a poetic idea.” In formulating such a thesis, Liszt could easily have invoked as evidence the bucolic tableau vivant of the Symphonie fantastique’s third movement, the quasi-cinematic sounds of the fifth or the recurring “idée fixe” that binds all five.

Notably, the version of the Symphonie fantastique that premiered in 1830 no longer exists. Its full score did not appear in print until 1845, by which time Berlioz had altered the work in ways big and small. The third movement, which Berlioz reported “made no impression at all” at the first performance, was probably the first significant part to undergo revision, followed by the second. By the time the Symphonie fantastique was next heard, on December 9, 1832, again at the hall of the Conservatoire, the first and fifth movements had also been revised, in part to better align the work with its wild “sequel,” Le retour à la vie. (It is this version of the Symphonie fantastique that Liszt arranged for solo piano and that Schumann used in his aforementioned review.) Berlioz’s artistic vision evolved over the decade, and he continued to tweak the symphony’s shapes and sounds well into his foreign tours of the early 1840s.

Berlioz would follow up the Symphonie fantastique with three more symphonies: the anti-concerto Harold en Italie (1834), the semi-operatic, seven-movement Roméo et Juliette (1839, rev. 1847) and the commemorative Symphonie funèbre et triomphale (1840, rev. 1842). As innovative as these follow-ups were, they have never held the same sway as Berlioz’s first symphony, which still teems with the passion, struggle, optimism, naivete and ingenuity of its revolutionary age.

— ©Jonathan Kregor, University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music

(Note: citations of Berlioz’s Mémoirs from David Cairn’s edition; early criticism from Thomas Forrest Kelly, First Nights: Five Musical Premieres; Liszt translation by the author.)