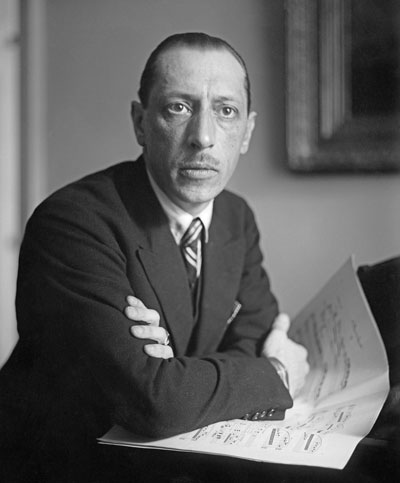

Igor Stravinsky

Born: June 17, 1882, Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg

Died: April 6, 1971, New York City

Petrushka

- Composed: 1910–1911

- Premiere: June 13, 1911, Paris, at the Théâtre du Châtelet (staged ballet) by the Ballet Russes, Pierre Monteux conducting; Michel Fokine, choreographer. Stravinsky revised the orchestration 1915–1946, and his final thoughts are known as the “Revised 1947 Version,” which is heard at these concerts.

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets (incl. bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, bass drum with attached cymbal, crash cymbals, snare drums, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, xylophone, harp, celeste, piano, strings

- CSO Notable Performances:

- First: November 1961, Max Rudolf conducting

- Most Recent: November 2019, Louis Langrée conducting.

- Duration: approx. 34 minutes

After the resounding success of The Firebird in 1908, Stravinsky became an instant celebrity in Paris. His name was now inseparable from the famous Ballets Russes, whose director, Sergei Diaghilev, was anxious to continue this most promising collaboration. Plans were soon underway for what eventually became The Rite of Spring. But events took a slight detour: in the summer of 1910, Stravinsky began writing a piece for piano and orchestra in which the piano represented for him “a puppet, suddenly endowed with life, exasperating the patience of the orchestra with diabolical cascades of arpeggios.” The puppet was none other than Petrushka, the popular Russian puppet-theatre hero, the equivalent of Punch in “Punch and Judy” shows.

When Diaghilev visited Stravinsky in Lausanne later in the summer, he expected his friend to have made some progress with The Great Sacrifice (the working title of The Rite of Spring); instead, he found him engrossed in a piece for piano and orchestra. Diaghilev immediately saw the dramatic potential of Stravinsky’s concert piece and persuaded the composer to turn it into a ballet. (The soloistic handling of the piano in the final version is a reminder of the original scoring.) Alexandre Benois, a Russian artist and longtime Diaghilev collaborator, wrote the scenario with Stravinsky, and designed the sets and costumes for the performance.

In traditional Russian puppet shows, Petrushka was, according to one description, “a devil-may-care oddball, a wisecracker and disturber of the peace.” As musicologist Richard Taruskin has pointed out, however, the hero of the ballet has little to do with that characterization. He is, rather, a reincarnation of the French Pierrot, the sad-eyed clown with a white face and wearing a white suit with large black buttons. The plot was based not on the Russian Petrushka plays but rather on the classical love triangle from the commedia dell’arte tradition from Renaissance Italy, involving Pierrot, Colombine and Harlequin (to use their French names, which are more relevant here). Yet in the first and last scenes, Benois re-created the atmosphere of the old shrove-tide fairs in Russia, a tradition he remembered from his childhood. The structure of the ballet, with two outer scenes depicting a Russian fair and two inner scenes representing a love story that transcends time and place, is more than a neat symmetrical device. It expresses a contrast between Russia and the West, between the public and the private spheres, and between the worlds of humans and puppets. Yet, as Taruskin writes:

…the “people”...are represented facelessly by the corps de ballet. Only the puppets have “real” personalities and emotions. The people in Petrushka act and move mechanically, like toys. Only the puppets act spontaneously, impulsively—in a word, humanly.

In composing the music of Petrushka, Stravinsky made use of an unusually large number of pre-existent melodies — either Russian folk music or popular songs of the time. These came to him from a wide variety of sources, ranging from the first scholarly collections of folk music, recorded with the then-new phonograph, to urban songs that were “in the air.” His treatment of these sources was far more radical, as far as harmonies are concerned, than it had been in The Firebird; especially in the second scene, “Petrushka’s Room,” we see significant departures from the techniques that Stravinsky had learned from his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov and that he had been following much more closely in his first ballet.

The first of the four tableaux (“The Shrove-Tide Fair”) is shaped by an alternation between the noise of the crowd and tunes played by street musicians. At first we hear a flute signal accompanied by rapid figurations that evoke the bustle of the fair. Soon the entire orchestra breaks into a boisterous performance of a Russian beggars’ song, followed by the entrance of two competing street musicians, a hurdy-gurdy player and one with a music box. Of the two popular tunes, heard first in succession and then simultaneously, one is a Parisian street-tune about the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt who had a wooden leg (Elle avait un’ jambe en bois—“She had a wooden leg”). This song, written by a certain Mr. Spencer, was protected by copyright, although Stravinsky didn’t realize this at the time of composition. As a result, he had to relinquish a percentage of the royalties from every performance of Petrushka to the author of the song or to his heirs. The other song was a well-known Russian melody, sometimes set to bawdy lyrics, that Stravinsky remembered from his youth.

The competition of the street musicians suddenly stops and the beggars’ song returns as a general dance. The signal from the beginning closes the first half of the tableau. Now the puppet theatre opens, and the Showman, playing his flute, introduces Petrushka, the Ballerina and the Moor to the audience. As he touches them with his flute, the three puppets begin the famous “Russian Dance,” in which the piano plays a predominant part. The irresistible force of this passage lies in the varied repetitions of short rhythmic figures and simple melodies harmonized with repeated or parallel-moving chords. The dance has a lyrical middle section where the same melody is played more softly by the piano, accompanied by the harp and winds. Finally, the loud version returns; the dance and the tableau end with a bang.

The second tableau starts with the sonority that has become emblematic of the work: two clarinets playing in two different keys at the same time. After a short piano cadenza, we hear a theme giving vent to Petrushka’s anger and despair at his failure to win the Ballerina’s heart. His fury suddenly changes to quiet sadness in the following slow pseudo-folksong, played by the duo of the first flute and the piano with only occasional interjections from other instruments. The Ballerina enters, and Petrushka becomes highly agitated. Then she leaves, and the earlier despair motif closes the tableau.

The third tableau takes place in the Moor’s room. His slow dance is accompanied by bass drum, cymbals and plucked strings, whose off-beat accents impart a distinctly East Asian flavor to the music. The melody itself is played by a clarinet and a bass clarinet pitched two octaves apart. Soon the Ballerina comes in (“with cornet in hand,” according to the instructions) and dances for the Moor as the brass instrument plays a rather simple tune accompanied only by the snare drum. She then starts waltzing to two melodies by Viennese composer Joseph Lanner (1801–43, a forerunner of the great Strauss dynasty), while the Moor continues his own clumsy movements (for a while, the two melodies are heard simultaneously). The waltz is abruptly interrupted as Petrushka enters to motifs familiar from the second tableau. His fight with the Moor is expressed by excited runs that, like Petrushka’s earlier music, are “bitonal” in the sense that the same melodic lines are played in two keys at the same time. The orchestra plays some violent, repeated fortissimo chords as the Moor pushes Petrushka out the door.

The fourth and last tableau brings us back to the fair, where, as the evening draws closer, more and more people gather for the festivities. A succession of numbers is performed by various groups taking turns at center stage. A group of nursemaids dances to the accompaniment of two Russian folk-songs which, according to a technique we have encountered earlier, are heard first in succession and then simultaneously. Next, a peasant enters with a bear that dances to the peasant’s pipe (the pipe is represented by the shrill sounds of two clarinets playing in their highest register). After this, a drunken merchant comes in: his tune is played in unison by the entire string section, with frequent glissandos, against a motley succession of ascending and descending runs in the woodwinds and brass. Two Romani girls perform a quick dance whose melody is given to the oboes and the English horn, with harps and plucked strings in the background, and then both the merchant’s tune and the Romani dance are repeated.

The Russian folksong of the coachmen and stable boys comes next, scored mainly for brass; that of the nursemaids, which began the whole scene, returns on clarinets and bassoons. The coachmen’s dance is taken over by the full orchestra, only to be suddenly displaced by the mummers, who, in their funny masks, jest and dance with the crowd to some loud and highly rhythmic music in which the brass predominates.

Suddenly the celebration is disrupted by a scream coming from the side of the theatre. Petrushka rushes in, pursued by the Moor who soon overtakes him and strikes him down. The two clarinets, whose dissonant intervals have followed Petrushka throughout the piece, emit a final piercing shriek that fades away in a pianissimo as the hero expires. Some soft woodwind solos, accompanied by high-pitched violin tremolos, lament Petrushka’s death. But as the Showman arrives to pick up the puppet and take him back to the theatre, Petrushka’s ghost appears overhead as a piccolo trumpet intones his melody in a tone that is aggressive, mocking and menacing at the same time. There are only a few string pizzicatos as the curtain falls; the last event in the piece is the resurgence of Petrushka the invincible, thumbing his nose at the magician and at the entire world, which had been so hostile to his pure and sincere feelings.

—©Peter Laki