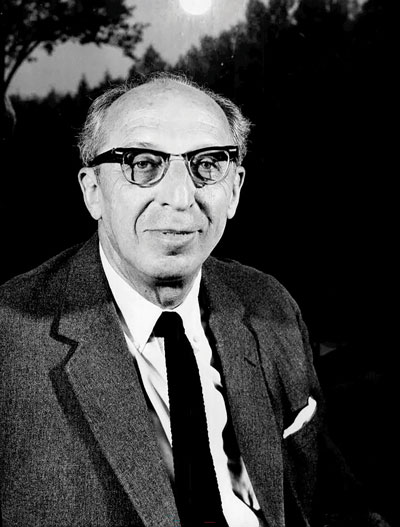

Aaron Copland

Born: November 14, 1900, Brooklyn, New York

Died: December 2, 1990, Sleepy Hollow, New York

Variations on a Shaker Melody from Appalachian Spring

- Composed: Full ballet, 1944; wind band version, 1956, orchestral version, 1967

- Premiere: Full ballet, October 30, 1944, at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, glockenspiel, triangle, harp, piano, strings

- CSO Notable Performances: Although the CSO has performed the Variations on a Shaker Melody many times over the decades on Educational, Parks and Pops concerts, this weekend marks the first CSO subscription performances.

- Duration: approx. 4 minutes

Aaron Copland’s Variations on a Shaker Melody came from the middle of things. The composer created the Variations by recomposing his variations on the now-familiar “Simple Gifts” Shaker tune at the narrative center of his score for Appalachian Spring (1944). Martha Graham, Copland’s collaborator on the ballet, had begun devising a scenario in 1942 initially around the Greek Medea myth, but upon Copland’s rejection of the idea she looked to the idealism of the composer’s Lincoln Portrait (1942). Secured with a commission from philanthropist Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, Copland set to work in 1943, provisionally titling the work “A Ballet for Martha,” which premiered as Appalachian Spring on October 30, 1944, at the Library of Congress. The ballet portrays vignettes around a Bride and Husbandman’s wedding as a Pioneer Woman, a Revivalist Preacher and his Followers mingle throughout. The “Simple Gifts” variations serve as the drama’s focal point, during which the betrothed perform an extended duet. If its characters seem like draft archetypes and its scenario plain, this has been to the ballet’s advantage, lending audiences an opportunity to see themselves in its personae.

While the Variations represent part of the larger work, Appalachian Spring itself is the rootstock of a longer, sustained creative project. Following Copland’s composition of the original 13-piece orchestral score, he devised a suite for both small and full orchestras that shed some transitional music. He went on to create the original wind-band version of the Variations in 1956 and the orchestral version of the same a decade later in 1967. In 1950, he even composed a poignant setting of “Simple Gifts” for solo voice and piano, part of his Old American Songs (1950, 1952). Over nearly a quarter century, Appalachian Spring and its sibling “Simple Gifts” often bloomed.

The orchestral Variations on a Shaker Melody play out such that individual sections indispensably construct a larger whole through processes of addition and subtraction, affecting a wide emotional range. Strings and a noble horn begin with “Simple Gifts,” but it is only the melody’s first half, an appetizer for what follows. Soon, a solo clarinet presents the melody in full at a faster speed, supported by punctuating flute. An oboe offers the first variation, counterpointing with other woodwinds, followed by a second variation with a tick-ticking accompaniment. Blazing brass herald variation three (marked “twice as fast”). The clarinet returns for a penultimate variation that sets up the culminating chorale-like finale, in which declamatory — even exclamatory! — brass take the lead. A brief coda teases the theme again, and those familiar with the full ballet may recognize a set of light chords that tie the Variations to its parent score.

Prior to Copland’s incorporation of it into Appalachian Spring, “Simple Gifts” was known primarily within the community of the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing — the Shakers — and it was Copland who brought it to its present renown. Neither a folk song nor a hymn, “Simple Gifts” was composed in 1848 by Maine Elder Joseph Brackett, possibly for dance. Building on growing interest in folk song collection in America during the first half of the century, which was led by prominent figures like Cecil Sharp and the Seeger family, historian Edward D. Andrews first brought “Simple Gifts” outside the Shaker community in a 1937 publication. Copland notes in the score’s preface that he found his version of “Simple Gifts” in Andrews’ 1940 anthology, The Gift to Be Simple: Songs, Dances and Rituals of the American Shakers. As Andrews places it, the tune was “sung everywhere in United Society,” and, for many, its text is emblematic of the Shaker ethos of utopian, egalitarian communal living:

'Tis the gift to be simple, 'tis the gift to be free,

'Tis the gift to come down where we ought to be,

And when we find ourselves in the place just right,

'Twill be in the valley of love and delight.

When true simplicity is gain’d,

To bow and to bend we shan't be asham'd,

To turn, turn will be our delight

'Till by turning, turning we come round right.

We might hear the text’s association of personhood with place and community in Copland’s choice to rework the theme from its original ballet and 13-piece orchestra. Copland also noted that he excerpted and rescored “Simple Gifts” for full orchestra from the ballet’s original small ensemble so it could be performed by school and community orchestras. On the one hand, this is entrepreneurial savvy. On the other, it captures a perception building around his music in the 1930s and 40s that his was a music of its nation. In basing a larger classical work on a folk or folk-sounding tune, Copland invokes a long tradition going back through the “Ode to Joy” finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. It also assumes a mantle of sourcing American musical songs and styles heard in the music of Copland’s predecessors and contemporaries like Antonín Dvořák, Charles Ives, Florence Price, William Grant Still and many others. Not coincidentally, “Simple Gifts” has since been used for other communal purposes. Songwriter Sydney Carter used the tune with new lyrics for his popular 1963 congregational hymn “Lord of the Dance,” and composer John Williams incorporated the tune into his Air and Simple Gifts for President Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration.

Beyond the creative processes and listening experiences of Appalachian Spring and the Variations is their place in a time of historical transition: the beginning of the end of World War II and the middle of the Cold War, respectively. By the time Copland completed Appalachian Spring for its October 1944 premiere, D-Day had passed on June 6 and V-E Day was just months away on May 8, 1945. Copland and Graham’s ballet reflects cultural circumstances that threw the arts into burgeoning modernist multiplicities, seeking answers to the War’s complexities: its story is spare, its choreography blends vernacular style with classical formation and contemporary angularity, and its original set by Japanese-born designer Isamu Noguchi evokes open landscapes through stripped-down, geometric asceticism. Meanwhile, questions swirled in the United States over what American music was and how it should sound. Many held Copland up as a paragon, and influences of New Deal art projects engaged with American heritage were in evidence as the Cold War wore on during the 1950s and 60s. To no small degree, Variations on a Shaker Melody hails from one of the most consequential periods of American political and cultural history.

—Jacques Dupuis, ©2025