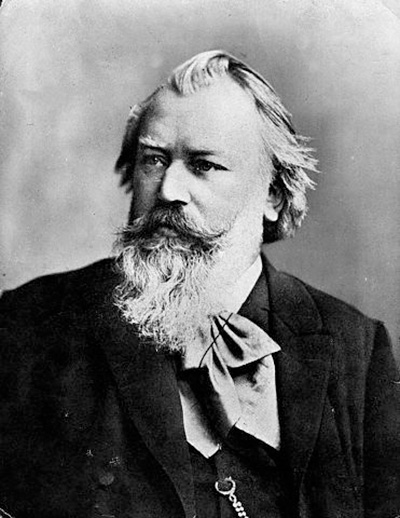

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80

- Composed: 1880

- Premiere: January 4, 1881, University of Breslau, Germany, Brahms conducting

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, triangle, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: February 1912, Leopold Stokowski conducting. Most Recent: February 2012, John Storgårds conducting.

- Duration: approx. 10 minutes

By the time he began composing the Academic Festival Overture, Johannes Brahms had established himself as one of the leading German composers of the late 19th century, in large part through the success of A German Requiem (Op. 45), Variations on a Theme by Haydn (Op. 56) and his first two symphonies. In 1879, the University of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) recognized his status by awarding him an honorary doctorate in philosophy and inscribing his diploma with the distinction “the greatest living German master of the strict musical style.” Only after accepting the honor did Brahms become aware that he was expected to write a new composition for Breslau. His friend Bernhard Scholz, who was the conductor of the Orchesterverein of Breslau and himself a composer, suggested he write a symphony. Instead, Brahms composed a one-movement orchestral work and, after some indecision, titled it Academic Festival Overture. He conducted its premiere in Breslau in January 1881. Two days later, while still in Breslau, he played the piano parts in performances of his Horn Trio (Op. 40) and two of his songs, as well as two of his rhapsodies for solo piano.

While writing the Academic, Brahms also composed the Tragic Overture (Op. 81), a far more tension-ridden, dramatic work, which he included in the concert that featured the premiere of the Academic. Today, these works are not usually performed during the same concert, but that was not the case in the 19th century. After the 1881 concert in Breslau, Brahms conducted performances of the Academic with numerous orchestras, including ones in Germany, Hungary and The Netherlands (where he had numerous admirers), sometimes including the Tragic on the same programs. In contrast, in the United States the works were usually performed on separate concerts. Whereas the Academic received its U.S. premiere in August 1881, the Tragic was premiered the next year. Theodore Thomas conducted the premiere of the Academic in a well-attended summer concert in Chicago, and he subsequently performed it with orchestras in other cities. When Thomas brought the Academic to Cincinnati in September 1881, the critic of the Cincinnati Enquirer praised the way the piece “gave full scope to the powers of the orchestra, both as to expression and execution.” American and European audiences greatly enjoyed the overture, and, from 1890 to 1902, it was one of Brahms’ most frequently performed compositions.

Brahms continued to conduct the Academic throughout the rest of his life. In 1895, he led a performance in Frankfurt am Main attended by Clara Schumann, his beloved friend and also his harshest critic. She had been one of the first people to hear the overture in 1880, in a piano version, and, after the 1895 performance, she observed the audience’s enthusiastic response to it and described the performance as “magnificent.” Brahms likely conducted the work for the last time in Berlin in 1896, in a concert during which he also conducted both of his piano concertos. Placing these two concertos on the same program is highly unusual, and, similarly uncommon, the Academic closed the concert. (An overture by Cherubini opened the concert.) This was likely the last concert that Brahms conducted before his death in April 1897.

The Academic Festival Overture pays tribute to university life by weaving in four student songs that were well known in Germany at the time. Toward the end of the introduction, we hear the hymn-like “Wir hatten gebauet ein staatliches Haus” (“We Had Built a Stately House”), written in 1819 by August von Binzer. Quietly intoned in long notes by the wind and brass instruments, it evokes an aura of nostalgia. The following first main section of the overture, which the full orchestra plays fortissimo and un poco maestoso (a little majestic), introduces two other songs, “Der Landesvater” (“The Father of Our Country”), also known as “Alles schweige, jeder neige” (“All is Silent, All Bow Down”), and “Was kommt dort von der Höh?” (“What Comes from the Heights?”), also known as the “Fuchslied” or “Fuchsenritt” (“Fox Song” or “Fox Ride”). The “Fuchslied,” which was associated with freshman hazing rituals, is particularly easy to identify because it is presented playfully by the bassoons, an instrument that composers often use to convey humor. The oboe answers the bassoons, as if launching a complicated fugue, perhaps referencing the “strict” style of music praised in Brahms’ diploma. Brahms, however, pokes fun at this convention and his reputation by discontinuing the fugal style and forcefully restating the melody in the full orchestra. Donald Frances Tovey, an English commentator and acquaintance of Brahms, described this passage as “the Great Bassoon Joke.” But apparently, the joke could not be repeated, and whereas “Der Landesvater” is restated in the Overture’s last main section, “Was kommt dort von der Höh?” is not.

The final student song “Gaudeamus igitur” only appears in the coda, where it provides a majestic, yet also somewhat amusing, conclusion. Although this hymn continues to be performed in a very grand manner during graduation ceremonies today, it originated as a lighthearted drinking song. Its original Latin lyrics exhort students to seize the day and enjoy life, for life is short. All of the popular songs likely reminded Brahms of his youth in Göttingen, a university town in Germany. These were fun times, but they were also crucial to his development as a composer. It was there, with friends such as the great violinist Joseph Joachim, that Brahms began refining his compositional skills in earnest, in part by learning from the advice and criticisms of his more experienced friends.

Brahms jokingly told friends that the Academic Festival Overture was “a potpourri of songs à la Suppé.” Franz von Suppé was a composer who rose to fame creating lighthearted works, and Brahms was likely referencing the overture to his operetta Flotte Bursche (“Jolly Students,” 1863), which also features a series of joyful student songs. He made a similarly humorous remark about his use of percussion instruments, including the triangle. The soft, detached opening melody accompanied by the cymbal and bass drum is one of the few times Brahms made use of these instruments. Percussion instruments are frequently used in music that imitates Turkish janissary bands, and at one point Brahms jokingly suggested he would title the work “Janissary Overture.” (He also considered titling it “Studentenlieder Overture” or “Viadrana Overture,” a reference to Breslau’s Oder River.)

Although Brahms could have composed a highly complicated symphony that demonstrated his “strict,” or academic, style, he instead created a wry, witty overture. It celebrates the fun of student life, which so many of us fondly recall, as well as the formality of university customs.

—©Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Ball State University