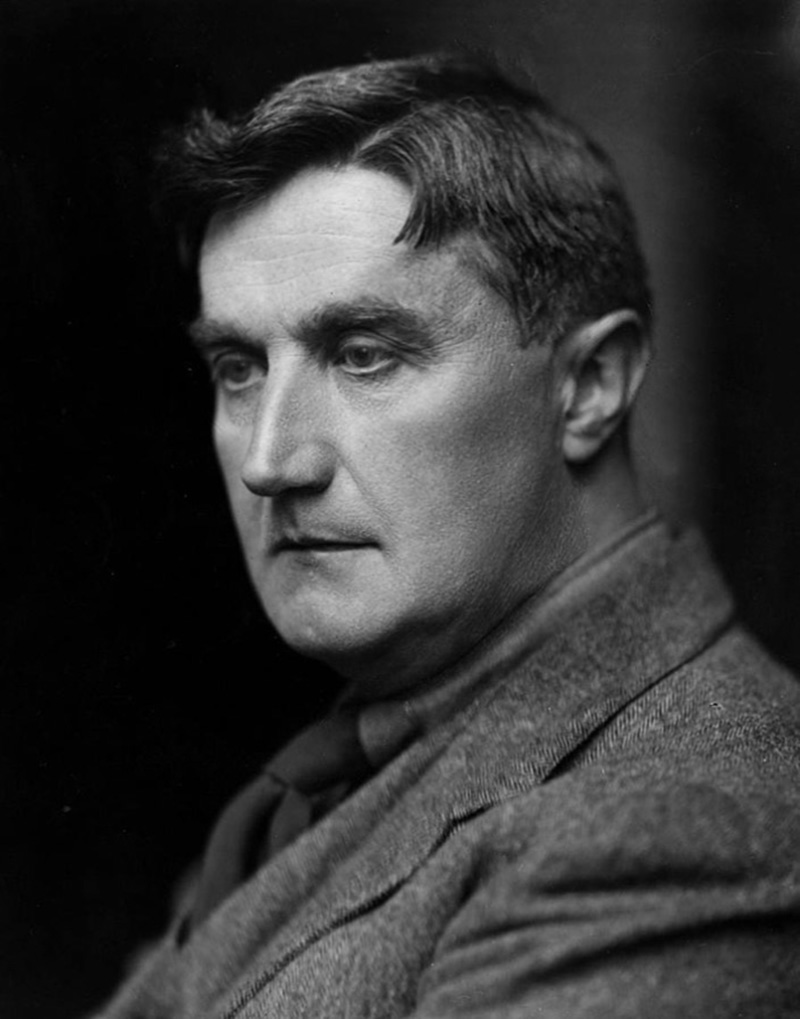

Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Born: October 12, 1872, Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, England

- Died: August 26, 1958, London

by E.O. Hoppé, 1921

Symphony No. 6 in E Minor

- Composed: 1944–47

- Premiere: April 21, 1948, London, Sir Adrian Boult conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, side drum, suspended cymbals, triangle, xylophone, harp, strings

- CSO notable performances: First and Most Recent: April 2015 with Vassily Sinaisky, conducting.

- Duration: approx. 31 minutes

The musicologist and author Deryck Cooke (best known for his completion of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony) recalled his first impressions of the Vaughan Williams Sixth in his book The Language of Music:

The effect on the present writer, at the first performance, was nothing short of cataclysmic: the violence of the opening and the turmoil of the whole first movement; the sinister mutterings of the slow movement, with that almost unbearable passage in which the trumpets and drums batter out an ominous rhythm, louder and louder, and will not leave off; the vociferous uproar of the Scherzo and the grotesque triviality of the Trio; and most of all, the slow finale, pianissimo throughout, devoid of all warmth and life, a hopeless wandering through a dead world ending literally in niente [nothing]...

Cooke was not alone in having such a strong response to the new work; it became one of the most successful symphonies of its time, with more than a hundred performances within two years of the premiere. Composed during and immediately after World War II, Vaughan Williams’ Sixth was widely assumed to be about the war, though the composer himself made no such statement and, in fact, strongly discouraged discussions of his music along programmatic lines. Yet no one could miss the fact that the dean of English composers, then in his mid-70s, had gone further than ever before in the exploration of dissonance and the large-scale integration of contrasts,” in the words of another prominent writer on music, Hans Keller. The work sharply contrasted with Vaughan Williams’ previous symphony, the serene Fifth; though also a wartime work, the Fifth was perceived as a fervent plea for peace and harmony, while the Sixth speaks a much harsher language, regardless of how we choose to interpret that harshness.

The four movements of the symphony are played without pauses (or, as RVW put it: “Each of the first three has its tail attached to the head of its neighbour”). The work opens with the kind of climactic outburst one would normally expect only after a long crescendo. Gradually, however, the music reaches a state of greater calm. The second theme introduces a more regular rhythmic pulsation, but elements of tension remain, since the stresses in the melody do not always coincide with those in the bass. With the third theme, a lyrical cantabile, complete harmony is almost achieved: in spite of the lyrical character, the active pulsation of the previous section remains constantly present, as if trying to counteract the melodic flow unfolding over it. This pulsation then grows more and more powerful and leads into a recapitulation of the “cataclysmic” opening. As a concluding gesture, the cantabile (“songlike”) melody returns, this time free from any unsettling counterpoint. The lush chords of the harp, entering here for the first time, enhance the soothing atmosphere.

The second movement is built upon an insistent rhythmic motive, heard almost constantly during the opening section. Its development culminates in a timpani roll and a startling bass fanfare, followed, as a total contrast, by a new lyrical idea introduced by the strings. Yet the insistent motive soon returns, first in an understated manner but then increasing in volume until the music erupts in another dramatic climax, even more passionate than the one in the first movement. A meditative English-horn solo concludes the movement, leading directly into the ferocious scherzo. The latter is driven, once more, by its rhythmic momentum; this time the fundamental idea is the alternation between different kinds of rhythmic motion: quarter-notes followed by quarter-note triplets followed by eighth-note triplets. The scherzo’s central trio section is a haunting solo for tenor saxophone accompanied by the snare drum. Both sections of this solo are repeated by the full orchestra, before an expanded recapitulation, at the end of which the trio melody reappears, played fortissimo by the entire orchestra.

A quiet transition, with clarinet and bass clarinet solos, connects the scherzo to the symphony’s last movement, the slow “Epilogue.” Its opening theme—similarly to the opening theme of the second movement—had been originally intended for, but not actually used in, a score Vaughan Williams wrote for a wartime film titled Flemish Farm. The symphonic finale unfolds as a succession of “whiffs of themes” (the composer’s own expression), with a great deal of contrapuntal development and meandering woodwind solos. In a rare concession to those who insisted on seeking extra-musical meanings in the work, the composer offered this quote from Shakespeare’s Tempest: “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.” In Prospero’s famous speech, all reality melts “into thin air” and “the great globe itself...shall dissolve”; similarly, at the end of Vaughan Williams’ symphony, the entire musical fabric disintegrates and only a faint E minor chord remains, in its most unstable inverted form, until that, too, fades into silence.

—Peter Laki