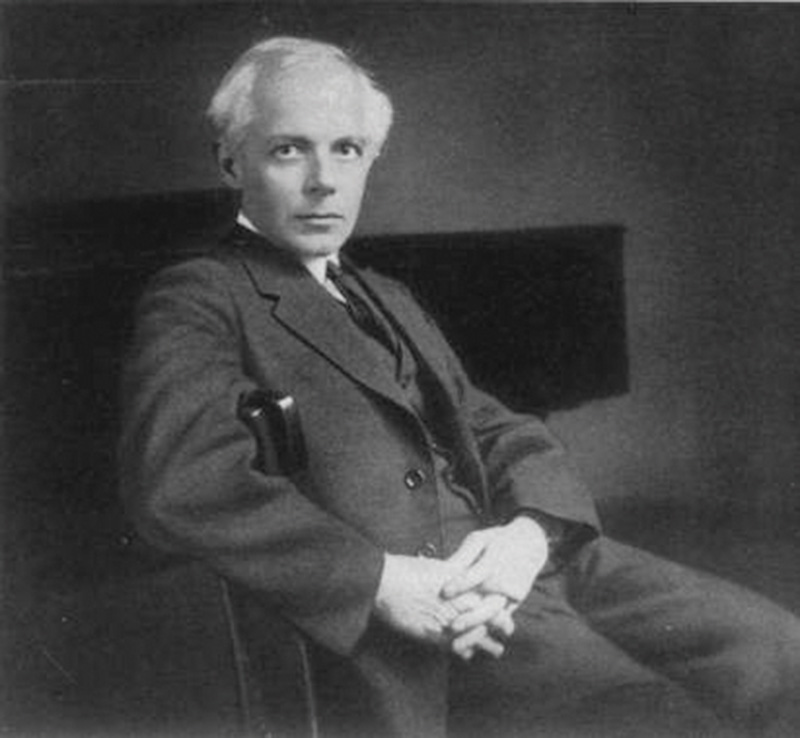

Béla Bartók

- Born: March 25, 1881, Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary (now Sânnicolau Mare, Romania)

- Died: September 26, 1945, New York City

Concerto for Orchestra

- Composed: 1943

- Premiere: December 1, 1944, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitzky conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), 3 oboes (incl. English horn), 3 clarinets (incl. bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, 2 harps, strings

- CSO notable performances: First Performance: November 1950, Thor Johnson conducting. Most Recent Performance: January 2018, Louis Langrée conducting. Other: The CSO recorded the Concerto for Orchestra in 2006 (Lutosławski/Bartók: Concertos for Orchestra), Paavo Järvi conducting.

- Duration: approx. 40 minutes

Bartók was 59 years old when he emigrated to the United States with his second wife and former pupil, Ditta Pásztory-Bartók. His adjustment to the new environment was made difficult, even traumatic, by several factors. Bartók, who had been the foremost musical celebrity in his native Hungary, became an émigré composer who, although not entirely unknown in the Western Hemisphere, was far from being a household name and had to struggle to relaunch his career here.

Bartók was ill-equipped for such a struggle. He was not prepared to make any compromises. He was not interested in university positions because he did not believe in teaching composition. He did concertize a little as a pianist, mainly in a two-piano duo with his wife and, a few times, as soloist in his Second Piano Concerto, yet his main ambition throughout this period was to continue his research in ethnomusicology. Having learned about Milman Parry’s collection of recordings from Yugoslavia, preserved at Columbia University, he devoted many hours to transcribing these recordings. He received a grant to do this work, but the grant ran out before Bartók could finish the project. It was also at this time—late in 1942—that Bartók’s health first began to deteriorate, with fevers, pain and weakness, but with no immediate diagnosis (the first signs of the leukemia that would claim his life in 1945).

The situation was grave indeed when one day Bartók, lying in a New York hospital, received an unexpected visit from Serge Koussevitzky, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Koussevitzky commissioned a new orchestral work in memory of his wife and left a check for half the amount of the commission on the composer’s bedside table. (He and everybody else took great pains to conceal from Bartók that the idea of the commission had come from two of the composer’s friends, violinist Joseph Szigeti and conductor Fritz Reiner; had Bartók known this, the commission would have seemed to him a form of charity that he might even have turned down.)

The commission quite literally gave Bartók, who had composed virtually nothing for the previous two years, a new lease on life. Work on the score proceeded rapidly, thanks in part to the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), which arranged for Bartók to spend the summer months of 1943 at a private sanatorium in Lake Saranac, New York. Bartók’s health improved, he gained some weight, and the full score of the Concerto for Orchestra was completed by October 8.

In opting for a five-movement form with a central slow movement and two quasi-scherzos in second and fourth place respectively, Bartók returned to a compositional design he had first discovered 40 years earlier in his Suite No. 1 for Orchestra and used again in his String Quartet No. 4 (1928). It was one of several symmetrical structures he favored in his large-scale works, one that afforded a great deal of diversity in character organized around a single governing principle.

The first movement opens with a slow introduction whose chains of ascending fourths, played by cellos and basses, create the impression of a world being born out of primeval chaos. The first “concertante” solo, for flute, still has something indecisive to it, but the second, for three trumpets, is a fully formed idea that borrows its formal structure (though not its actual melody) from Hungarian folksong. The tempo gradually increases and reaches Allegro vivace; the fast section is dominated by two themes, both of which, like the theme of the introduction, are built on ascending fourths. This energetic music is only temporarily interrupted by a lyrical interlude in which the oboe and the harp seem to carry on an intimate conversation.

The second movement, Giuoco delle Coppie (“Game of Pairs”), opens and closes with a brief snare drum solo. Five pairs of wind instruments play their themes in parallel intervals; we hear, in turn, two bassoons in sixths, two oboes in thirds, two clarinets in sevenths, two flutes in fifths, and finally, two muted trumpets in major seconds. A short brass chorale functions as a middle section before a full (varied) recapitulation.

The third-movement Elegy opens with some ascending fourths that clearly allude to the first movement’s slow introduction. The glissandos on the harp and the soft woodwind figuration recall a moment in Bartók’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle, when the opera’s heroine, Judith, sees the Lake of Tears behind the sixth door of the castle. The middle section of the Elegy is based on the same quasi-folksong we heard in the introduction to the first movement. Played this time by the full orchestra, it sounds much more tragic than before. The movement ends with a haunting piccolo solo, after which the boisterous string unisons of the fourth movement come as quite a jolt.

Bartók told his pupil György Sándor a little story he had associated with the fourth movement Intermezzo interrotto (“Interrupted Intermezzo”). A young man serenades his sweetheart but is attacked by a gang of drunkards. Despite the pain he feels, he continues his serenade. (This story was evidently influenced by Debussy’s piano prelude, La sérénade interrompue.)

There are some clues in the movement that reveal a meaning deeper than the story would suggest, however. Many people think that the beautiful cantabile melody played by the violas is a rhythmically modified version of a melody from Zsigmond Vincze’s The Bride of Hamburg, a Hungarian operetta from the ‘20s, “Hungary, you are beautiful...”—and it is obvious that the real subject of the movement is Bartók’s nostalgia for his native land. And since the time was 1943, it is equally obvious what caused the disruption of the idyll. This disruption has caused a great deal of commentary because Bartók appeared to be parodying a prominent passage from Shostakovich’s Seventh (“Leningrad”) Symphony, which had recently created a major sensation in the United States. In his 2002 book My Father, Bartók’s younger son Peter tells the story of how Bartók listened to the radio broadcast of Shostakovich’s Seventh and objected to what seemed endless repetitions of the same theme. (The similarity to the song “Da geh ich zu Maxim” from Lehár’s operetta The Merry Widow does not seem to have been intended by either Bartók or Shostakovich.)

It should be noted that the Shostakovich melody, variously referred to as the theme of war or fascism, had its own sarcastic overtones that Bartók either missed or ignored. Moreover, its function in the symphony was to “interrupt” peaceful life, just as its Bartókian parody interrupted a peaceful serenade.

After the crude interruption by the trivial melody—greeted by an unmistakable “musical laughter” in the orchestra—the nostalgic evocation of beautiful, splendid Hungary returns, much softer than the first time, as if through a veil, a memory of a memory. Then the innocent little intermezzo tune ends the movement, as if dismissing the whole drama with a shrug of the shoulders.

The finale belongs to the type of last movements inspired by the spirit of folk-dance Bartók used at the end of many of his major works. After the opening horn fanfare, the violins start a perpetual motion in rapid sixteenth-notes that runs through almost the entire movement. In the central section, a large-scale fugato (a section based on imitative counterpoint) unfolds. After a recapitulation that includes a brief lyrical episode in a slower tempo, the final crescendo begins, leading to a powerful climax at the end of the composition.

—Peter Laki