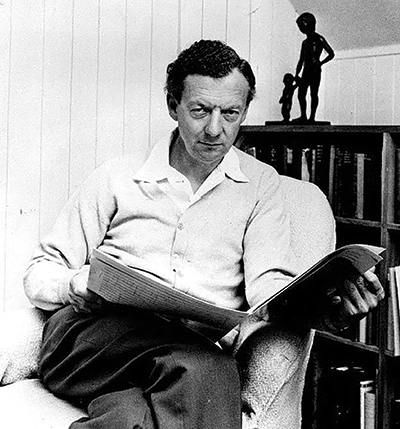

Benjamin Britten

- Born: November 22, 1913, Lowestoft, United Kingdom

- Died: December 4, 1976, Aldeburgh, United Kingdom

Concerto No. 1 for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 15

- Composed: 1939

- Premiere: March 29, 1940, New York, John Barbirolli conducting the New York Philharmonic, Antonio Brosa, violin

- Instrumentation: solo violin, 3 flutes (incl. 2 piccolos), 2 oboes (incl. English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tenor drum, triangle, harp, strings

- CSO notable performances: First Performance: October 2006, Andrey Boreyko conducting and Hilary Hahn, violin. Most Recent Performance: May 2017 with Robert Treviño conducting and Midori, violin.

- Duration: approx. 34 minutes

The 1930s were an extraordinary decade for violin concertos. Within ten short years, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Schoenberg, Berg, Bartók, Szymanowski, Walton and Barber (an incomplete list) all wrote major concertos without which the violin repertoire would never be the same. And before the decade was out, a young Benjamin Britten added another masterpiece to this rich musical harvest—a composition that may have been overshadowed by some of its distinguished contemporaries and, in fact, by Britten’s own later music, but it fortunately has been heard more frequently in recent years.

Britten’s Concerto was written for a Catalan violinist named Antonio Brosa (1894–1979), who premiered it at Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic under John Barbirolli on March 28, 1940. Britten and his professional and personal partner, the tenor Peter Pears, had been living in the United States since June 1939; they knew that war in Europe was imminent and, as committed pacifists and conscientious objectors, they wanted to remove themselves from the dangerous scene. Yet if they were able to escape physically, they couldn’t help being emotionally affected by the tragic times. Britten had actually begun working on his Violin Concerto in England the year before, ‟with a somewhat dutiful air,” as biographer Humphrey Carpenter writes. By the time the work was finished after Britten’s move across the Atlantic, it certainly no longer had anything dutiful about it. It is a passionately dramatic, vibrant work, commonly interpreted as a requiem for the victims of the Spanish Civil War. In fact, Britten had just visited Spain in 1936, the year the war broke out, for a music festival in Barcelona. There Antonio Brosa performed Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, which demonstrably influenced Britten. Brosa and Britten also played Britten’s Suite for Violin and Piano at the same festival.

Britten’s Violin Concerto opens with a timpani solo playing a fundamental rhythmic motif that is subsequently used as counterpoint to the violin’s lyrical melody. The diabolical scherzo that follows the haunting first movement in some ways foreshadows Shostakovich’s First Concerto, written almost a decade later. Its middle section, which obsessively develops a relatively simple, almost folk-like, theme, culminates in a stunning trio for two piccolos and tuba, which in turn leads into the recapitulation. Britten inserted his cadenza before the finale (again anticipating Shostakovich); the cadenza is based on the rhythmic motif with which the whole work began. The final movement is written in the form of a passacaglia, a set of variations on a bass melody first presented by the three trombones. The variations grow more and more animated until, suddenly, the tempo broadens to largamente, preparing for the recitative-like lament that ends the work with the musical equivalent of a question mark.

—Peter Laki