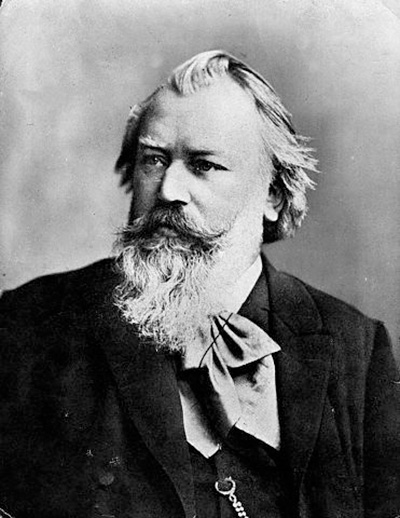

Johannes Brahms

- Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

- Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

String Quartet No. 3 in B-flat Major, Op. 67

- Composed: 1875, while on vacation in Ziegelhausen near Heidelberg

- Premiere: October 30, 1876 in Berlin by the Joachim Quartet

- Duration: approx. 34 minutes

On a program of music by Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020) and John Harbison (b. 1938), how does the 19th-century Viennese composer Johannes Brahms fit?

Brahms, without renouncing beauty and emotion, proved to be a progressive in a field which had not been cultivated for half a century… progress in the direction toward an unrestricted musical language which was inaugurated by Brahms the Progressive.

The above statement from the oft-quoted article by Arnold Schoenberg, “Brahms the Progressive” from his 1950 book Style and Idea, provides at least a philosophic reason: Brahms is the composer who opened the door to a free musical language, which ushered in the age of the “emancipation of the dissonance” (Schoenberg’s term) and compositional techniques such as 12-tone, free atonality and extended tertian harmony. Within the context of our modern ears, the innovation of Brahms’ music is, perhaps, lost to us, but within the context of this program we can hear the progressiveness that Schoenberg did.

The compositional shadow of the 122 string quartets written by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven loomed over Brahms, and he painstakingly revised and edited his first two string quartets for nearly a decade before they were published in 1873 as Op. 51. Brahms would contribute only one additional quartet to the repertoire, Op. 67.

Brahms equally toiled over the symphonic genre. He started his first symphony in 1862 and it remained unfinished in 1875. He wrote to his friend Franz Wüllner in the summer of 1875, “I stay sitting here, and from time to time write highly useless pieces in order not to have to look into the stern face of a symphony.” One of these “useless pieces” was the Op. 67 string quartet.

The first two of Brahms’ string quartets are dark, dramatic, broody and often sentimental. In contrast, the third is witty, light-hearted and, as Clara Schumann wrote, “too delightful for words.” This change in character has not diminished the technical demands nor his compositional novelty. As James M. Keller wrote, “We find Brahms not less proficient in his mastery—Brahms always astonishes—but he seems to a large degree freed from his compositional demons.”

—Tyler M. Secor