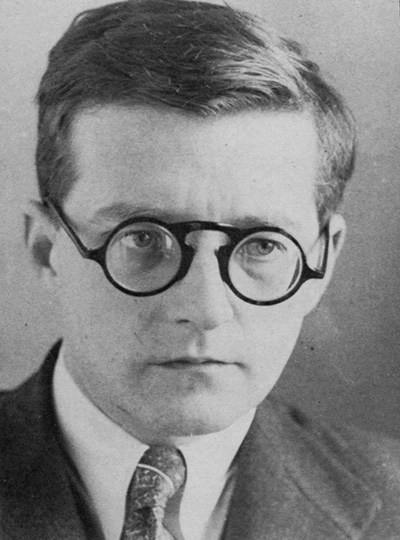

Dmitri Shostakovich

- Born: September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- Died: August 9, 1975 in Moscow

Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47

- Composed: 1937

- Premiere: November 21, 1937, Evgeny Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, tam-tam, triangle, xylophone, 2 harps, celeste, piano, strings

- CSO notable performances: First Performance: October 1942, Eugene Goossens conducting. Most Recent: September 2016, Louis Langrée conducting.

- Duration: approx. 44 minutes

Shostakovich wrote the Fifth Symphony in what was certainly the most difficult period in his life. On January 28, 1936, an unsigned editorial in the Pravda, the daily paper of the Soviet Communist Party, brutally attacked his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, denouncing it as “muddle instead of music.” This condemnation resulted in a sharp decrease of performances of Shostakovich’s music for about a year. What was worse, Shostakovich, whose first child was born in May 1936, had to live in constant fear of being deported to one of the infamous, deathly labor camps in Siberia. These were the days of the “Great Terror” that claimed the lives of some of the country’s greatest artists, such as the poet Osip Mandelstam, the novelist Isaac Babel, and the theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold. It is said that Shostakovich kept a suitcase with a change of clothes under his bed, in case they would come for him in the middle of the night.

Yet the composer was miraculously spared: the Party decided that the country’s musical life couldn’t afford to lose its greatest young talent. Shostakovich was granted a comeback. Less than a year after being forced to withdraw his Fourth Symphony, he heard his Fifth premiered with resounding success in Leningrad on November 21, 1937.

Could it be that the qualities in the Fifth Symphony that are so admired today were the same ones that saved the composer’s life then? Shostakovich clearly made a major effort to write a “classical” piece here, one that would be acceptable to the authorities and was as far removed from the avant-gardistic Fourth as possible. Whether that makes it “A Soviet Artist’s Creative Response to Just Criticism,” as it was officially designated at the time, is another question. The work is so profound and sincere as to transcend any kind of political expediency. The symphony was definitely a response to something, but not in the sense of a chastised schoolboy mending his ways—rather as a great artist reacting to the cruelty and insanity of the times.

The energetic dotted motif at the beginning of the Fifth Symphony is, no doubt, dramatic and ominous. A second theme, played by the violins in a high register, is warm and lyrical but at the same time eerie and distant. The music seems hesitant until the horns begin a march theme that leads to motivic development and a speeding up of the tempo. It is not a funeral march, but it is not exactly triumphant either. Reminiscent of some of Mahler’s march melodies but even grimmer, its harmonies modulate freely from key to key, giving the march an oddly sarcastic character. At the climactic point of the march, the two earlier themes return. The dotted rhythms from the opening are even more powerful than before, but the second lyrical theme, now played by the flute and the horn to the soothing harmonies of the harp, has lost the edge it previously had and brings the movement to a peaceful, almost otherworldly close.

The brief second movement Scherzo brings some relief after the preceding drama. Its Ländler-like melodies again bespeak Mahler’s influence, both in the Scherzo proper and the Trio, whose theme is played by a solo violin and then by the flute.

The third movement is an expansive Largo in which the brass is silent and the violins are divided into three sections, not the usual two. After an espressivo melody, scored for strings only, two flutes and harp transform the first movement’s march rhythm into a lament. The oboe, the clarinet and the flute intone desolate solo melodies, interspersed with a near-quote from a Russian Orthodox funeral chant played by the strings. The tension grows and finally erupts about two-thirds through the movement; the opening melody then returns in a passionate rendering by the cello section in a high register. At the end, the music falls back into the lament mode of the earlier woodwind passages.

Generally accepted as the emotional high point of the symphony, the Largo was widely understood as a lament for the Soviet Army marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who fell victim to the Stalinist purges in 1937. Tukhachevsky had been a benefactor and a personal friend of the composer’s. At the first performance, many people wept openly during the Largo, perhaps thinking of their own loved ones who had disappeared.

The last movement finally resolves the tensions that have built up in the first three movements (or so it seems at first) by introducing a march tune that is much simpler and more straightforward than most of the symphony’s earlier themes. Yet, after an exciting development, the music suddenly stops on a set of harsh fortissimo chords, and a slower, more introspective section begins with a haunting horn solo. The late musicologist Richard Taruskin pointed out that this section quotes from a song for voice and piano on a poem by Alexander Pushkin (“Vozrozhdenie” or “Rebirth,” Op. 46, No. 1) Shostakovich had written just before the Fifth Symphony. (“Delusions vanish from my wearied soul, and visions arise within it of pure primeval days....”) This quiet intermezzo ends abruptly with the entrance of the timpani and snare drum ushering in the recapitulation of the march tune, which is played at half its original tempo. Merely a shadow of its former self, the melody is elaborated contrapuntally until it suddenly alights on a bright D-major chord in full orchestral splendor, which then remains unchanged for more than a minute, until the end.

—Peter Laki