Ragtime, The Musical

by Dr. Scot Buzza

It can be difficult to provide historical context to a story without seeming to excuse past misogyny, racism, antisemitism and xenophobia. Thus, in the opening song of Ragtime, when the residents of New Rochelle sing “There were no negroes and there were no immigrants,” audiences cannot help but flinch. This is not happenstance: the authors put us on notice from the first notes that the power of this story lies in the blunt honesty with which it is told. There will be no punches pulled.

Ragtime is thoroughly American. It is a story about three American families, written by three American authors who take on three painful subjects: our American history, our American society and our American Dream. What lyricist Lynn Ahrens, author Terrence McNally and composer Stephen Flaherty have to say is not always easy for us to hear. They do away with the Sousa-march Americana, the flag-waving, and the red-white-and-blue hymns to The Way We Never Were, and instead reveal the intolerance, abuse, discrimination, poverty and gun violence. They challenge the myth of the Great Melting Pot with stories of aggression, antagonism and powerlessness. In the voices of historical figures such as Henry Ford, Emma Goldman, Evelyn Nesbit, J. P. Morgan, Booker T. Washington and Harry Houdini, they refute notions of American exceptionalism. They present all this against the backdrop of the journalistic sensationalism, political activism and social upheaval of the early 1900s, the ideal metaphor for which is, of course, the lopsided rhythms and the jagged tunes of the era’s quintessential musical genre: ragtime.

Ragtime: “Giving the Nation a New Syncopation”

.png)

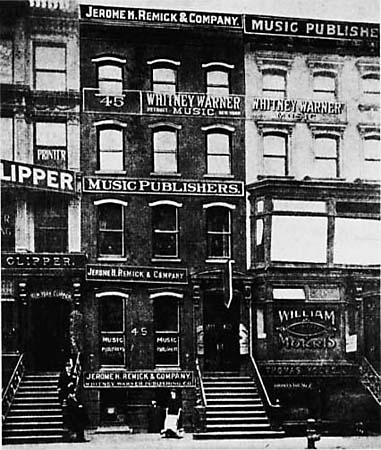

Ragtime is a pianistic genre that originated within African American communities in the late 1800s and spread north, aided to no small degree by the development of the print music industry, the popularity of the player piano, the phonograph, and the concentration of African American culture in urban areas. Further gentrified through Vaudeville (and later, as an unintended consequence of Prohibition), ragtime became the first African American genre to influence mainstream popular culture, as musicians such as Scott Joplin, James Scott and Jelly Roll Morton became public figures.

By the early 1900s, ragtime seemed to be everywhere. Tin Pan Alley publishers churned out a stream of piano rags and ragtime-style songs. Ragtime contests rewarded performers for their technical mastery and their improvisational skills. Musical characteristics of the idiom, including complex syncopations and metrical displacement, soon saturated entertainment intended for upper class white audiences in a way that was not always welcome. At the 1901 convention in Denver, the American Federation of Musicians adopted a resolution characterizing ragtime as “unmusical rot,” urging union members to “make every effort to suppress and discourage the playing and the publishing of such musical trash.” A popular publication for music pedagogues, The Etude, warned, “The counters of the music stores are loaded with this virulent poison which, in the form of a malarious epidemic, is finding its way into the homes and brains of the youth to such an extent as to arouse one’s suspicions of their sanity.”

Ragtime: “And There Were No Immigrants”

_caption_ Mulberry Bend, circa 1888.jpg)

By the early 1900s, the era in which Ragtime takes place, New York City already had a population of over 3.5 million. The great waves of European immigrants, the consolidation of five boroughs into one vast city, the development of the city’s infrastructure, and the unprecedented construction boom all contributed to the city’s prestige as the “new metropolis.” Yet, its gritty underbelly was unmistakable. Its numbers swelled further due to the Great Migration, as six million African Americans moved from the rural south to the northeastern cities to escape racial violence and pursue economic and educational opportunities. In New York, they met with legally ratified discrimination in employment and housing, as boroughs implemented restrictive covenants and redlining, created segregated neighborhoods, and laid the foundation for current racial wealth disparities in the United States.

EDWIN LEVICK_COURTESY THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY.jpg)

The prosperity of American cities had been built on the labor of millions of immigrants, and turn-of-the-century New York was no exception. Over 70 percent of new arrivals entered the country through the immigration station at Ellis Island, including Jewish families escaping persecution in Eastern Europe. Often poor, alone and speaking little English, they toiled in the cramped sweatshops—children and adults alike—working 12-hour days, seven days a week for an average of 17 cents an hour. At night they huddled in the unheated tenement slums of the Lower East Side of Manhattan without plumbing or ventilation—as many as 15 to a room. High levels of corruption in both industry and city government made reform impossible, even after the death of 146 workers, mostly young women, some as young as 14, in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire exposed calculated disregard for the safety of workers.

The experience of white families differed in nearly every respect to that of immigrants and non-whites. At both local and national levels, government policies were explicitly designed to increase and segregate housing for the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant middle and upper class. As urban populations swelled, “white flight” to suburban New York surged. One such suburb, New Rochelle, ousted its local leaders by incorporating and then had itself redesigned and landscaped specifically to attract affluent white families. Developers made millions while New Rochelle itself, boasting manicured parks and new winding boulevards, became the wealthiest city, per capita, in New York State and the third wealthiest in the country.

Gender ideals of the early 1900s prescribed that upper- and middle-class men and women occupy separate domains, the former earning money while the latter bore children and managed the household. Among the working class, many women were forced through economic necessity to hold jobs in the manufacturing sector: by 1910, women constituted nearly 27 percent of the labor force in New York State. Services that were deemed wifely, such as cooking and cleaning, were increasingly supplied at an industrial level. Steam laundries hired women at low wages to wash, iron and mend for both private clients and commercial enterprises such as hotels and hospitals. Women scrubbed floors on their knees late into the night, in restaurants whose menu prices would be forever out of their reach. Even matrimonial sex in the household was often outsourced, supplemented by mistresses kept in hotels and apartments as well as by professional courtesans.

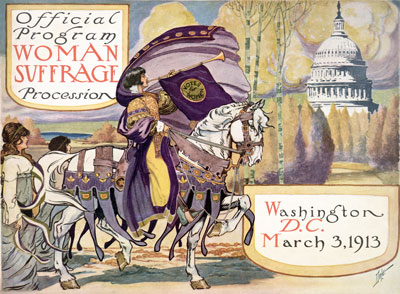

The experience of injustice did not necessarily open victims’ eyes to the full spectrum of oppression. When debates about gender and voting rights entered public consciousness, the National American Woman Suffrage Association shot itself in the foot by pandering to race and class prejudices instead of advocating for rights for all women. To their first national protest, a 1913 suffrage parade in Washington D.C., they first invited—and then disinvited—women of color to participate.

Ragtime: “And Everything Was Ragtime”

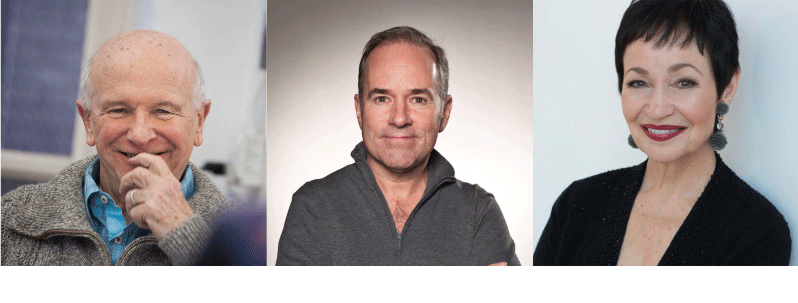

L. Doctorow, the author of the 1975 novel on which Ragtime is based, rooted his story in historical events of turn-of-the-century New York City. When producer Garth Drabinsky secured the rights to the novel, he and playwright Terrence McNally took the unusual step of auditioning potential composers and lyricists, eventually settling on lyricist Lynn Ahrens and her collaborator, University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music-trained composer Stephen Flaherty. The pair already had an impressive track record of successes, including Tony nominations for Best Musical, Best Book and Best Score for Once on This Island.

Ragtime premiered in Toronto in 1996 and opened on Broadway in 1998, where it ran for two years. The production received 13 Tony Award nominations and won four: Best Score, Best Book, Best Orchestrations and Best Supporting Actress for Audra McDonald. In 2004, it received 13 Drama Desk nominations, as well as six Olivier Award nominations. In 2009, it won the Tony Award for Best Revival of a Musical. The show’s original creators, McNally, Ahrens and Flaherty, have collaborated on the symphonic concert version heard here.

Ragtime has received its share of critique. Some found the story and subject matter uncomfortable, particularly the dynamics of race, class and gender. Some found the original production too slick and overproduced for a story about industrialization and the labor movement. However, praise for Ragtime’s glorious score has been nearly unanimous. Indeed, the show’s strength lies in its central conceit: when an emotion or a problem becomes too complex or overwhelming for an onstage character to address directly, it becomes the catalyst to express those feelings in song. By transitioning into the heightened medium of music, the authors transcend the limitations of speech in a way that allows their characters, and us, the audience, to address difficult topics such as love, death, injustice and hope. It allows us to hear the difficult truths we don’t want to hear, to look at the ugliness that usually repels us. The creators of Ragtime never need to resort to banalities or nostalgia for centuries past. Instead, they offer us an honest examination of the discrepancies between who we say we are and who we really are as a community, as a society and as a nation—right here and right now.

Interested in learning more about the historical figures and social events of Ragtime? Check out one of these suggested titles from the Cincinnati Public Library.