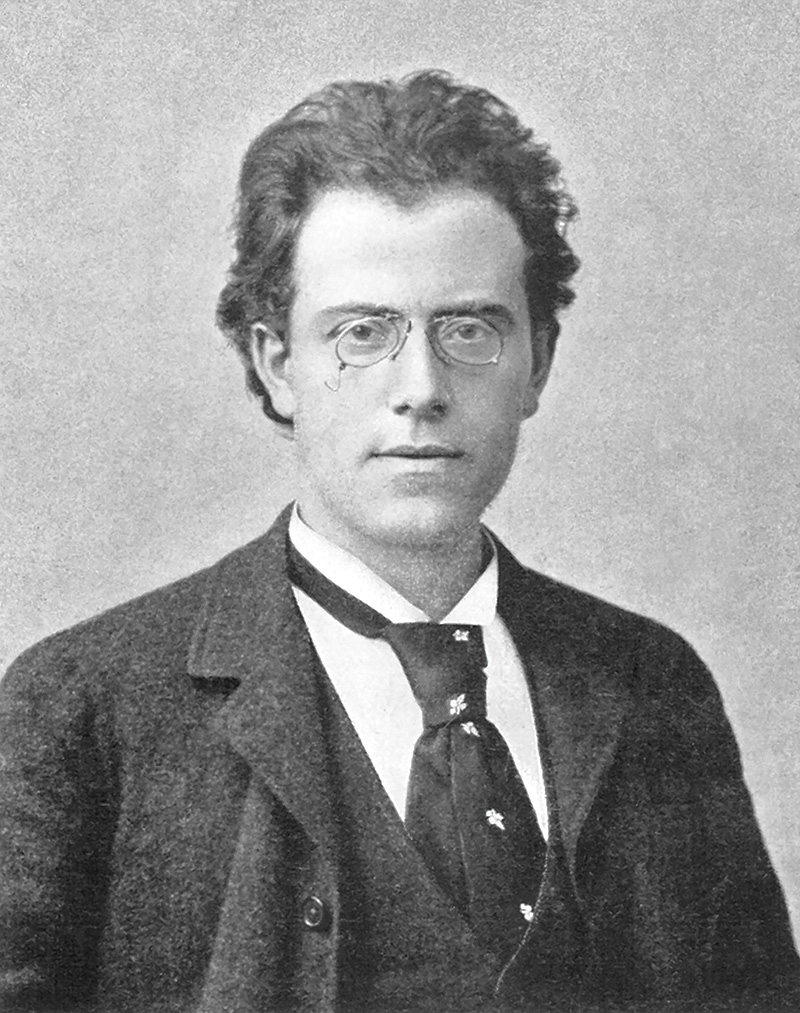

Gustav Mahler

- Born: July 7, 1860, Kalischt Bohemia

- Died: May 18, 1911, Vienna

Symphony No. 7 in E Minor

- Composed: 1904-05

- Premiere: September 19, 1908 in Prague, conducted by the composer

- Instrumentation: 4 flutes (incl. piccolo), piccolo, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tenor tuba, tuba, timpani, bass drum, bass drum with attached cymbal, cowbell, crash cymbals, deep bells, glockenspiel, herdbells, rute, small bells, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, 2 harps, guitar, mandolin, strings

- CSO notable performances: First Performance: March 1931, Fritz Reiner conducting. Most Recent Performance: February 2011, Paavo Järvi conducting.

- Duration: approx. 80 minutes

“For the first time in musical history,” wrote German composer and conductor Hans Werner Henze of Mahler’s symphonies in his 1982 collection of essays titled Music and Politics, “music is interrogating itself about the reasons for its existence and about its nature.... It is a knowing music, with the same tragic consciousness as Freud, Kafka, Musil.”

As Henze’s trenchant comment indicates, it was Gustav Mahler who thrust music into the modern age, the 20th-century time of self-doubt and uncertainty and dizzyingly fast change. Mahler was increasingly convinced that the 19th-century world he knew was about to crack; that the political, social and artistic institutions and customs that shaped his era were being drawn inexorably toward some unnameable cataclysm; that despite the period of prosperous peace in which he lived—from 1870 to 1914, among the longest in European history—that the times were badly, perhaps irreparably, out of joint. The forces that ignited World War I were already swinging into place by the turn of the 20th century, and Mahler came to believe that life as he knew it would be destroyed and would never come again; that he, as heir to two centuries of the greatest and most profound German music, was creating the last compositions of a symphonic heritage extending back through Brahms and Beethoven to Mozart and Haydn. In the words of Edward Downes, “The composer felt that the entire tradition, the works of the past he loved, the values by which he lived, even the sensitivity to perceive these things—were all sliding with him irretrievably into oblivion.” Much of the power and poignancy of Mahler’s music arises from his inimitable juxtaposition of these universal concerns with the simple, personal joys of nature, family and love.

The tradition inherited by Mahler comprised the two great symphonic rivers that flowed through the 19th century, both with sources in the music of Beethoven. One, an essentially Romantic strain, arose from the extra-musical references and explicit expression of the Third (“Eroica”), Sixth (“Pastoral”) and Ninth (“Choral”) symphonies, and inspired (and was used as justification for the daring formal experiments of) Berlioz, Liszt and other composers of “program” music. The complementary stream, grown from the Classical tradition of “pure” or “abstract” music (both slippery terms; perhaps “not deliberately referential” would be better, though more cumbersome), coursed through Beethoven’s Fourth, Fifth, Seventh and Eighth symphonies and into the orchestral music of Brahms (always), Schumann (usually) and even Tchaikovsky (occasionally). It was to the first of these manners, the referential, that Mahler was initially attracted as a symphonic composer. His Symphony No. 1 begins with an evocation of verdant springtime filled with the natural call of the cuckoo and the man-made calls of the hunt, and it takes as its main thematic material the second of the Songs of a Wayfarer, the folk-like “Ging heut’ Morgen übers Feld” (“I Crossed the Meadow this Morn”). The Second Symphony (“Resurrection”) began as a tone poem titled Totenfeier (“Funeral Rite”), which, in the fullness of its gestation, demanded from Mahler a choral acclamation to fulfill its grand spiritual progression. (“I always arrive at a point where I must employ the ‘word’ as the bearer of my musical idea,” he admitted at the time.) The Third Symphony, an immense paean for contralto, chorus and orchestra to Creation itself, included evocative titles for each of its six movements: “Pan awakes; Summer marches in”; “What the flowers of the meadow tell me”; “What the night tells me”; and so forth. (Mahler called the finale, rather conspiratorially, “What God tells me.”) So abundantly did this subject inspire Mahler’s creativity that he had enough material left over to begin another symphony—the child’s vision of heaven that serves as the vocal finale of the Fourth Symphony was actually an “out-take” from the Symphony No. 3. Mahler, through 1900, the year of the Fourth Symphony, was very much a composer of Romantic, “referential” orchestral music.

In 1902, beginning with the Fifth Symphony, Mahler dramatically changed his compositional style. “Gone are the folk inspiration,” wrote Deryck Cooke, “the explicit programs, the fairy-tale elements, the song materials, the voices; instead, we have a triptych of ‘pure’ orchestral works, more realistically rooted in human life, more stern and forthright of utterance, more tautly symphonic, with a new granite-like hardness of orchestration.” The technique driving this reorientation of Mahler’s creative idiom was a concentration on motivic development realized through what Egon Gartenberg called a “volcanic change to modern polyphony.” This new method yielded the symphonies nos. 5, 6 and 7, which call for instruments only, without voices, and largely eschew programmatic reference. The Fifth Symphony is the most “abstract” work Mahler ever wrote; the Sixth, the most Classically pure in its form, though its funeral-dirge ending and controversial hammer blows representing the strokes of Fate have lent it the sobriquet “Tragic.” Concerning the Symphony No. 7, Alma, the composer’s wife, noted, “As he wrote the serenade [i.e., the fourth movement], he was beset by Eichendorff-ish visions—murmuring springs and German Romanticism. Apart from this, the Symphony has no context.” There are, of course, other referential tangents emanating from the Seventh Symphony (the nocturnal evocations of the two “night music” movements; a possible allusion to Wagner's Die Meistersinger in the finale; the tenor horn solo of the opening, of which Mahler said, “Here Nature roars”), but, compared with the specificity of the first four symphonies, is largely devoid of external associations.

What brought about the radical change in Mahler’s symphonism in 1902? Heinrich Kralik’s comments typify a certain bafflement among scholars: “Nothing is known of any outward experiences or inner transformations during that period which could account for the new mode of expression. There was no outward struggle which could have threatened the composer’s career [which then centered on directing the Vienna Opera] and shattered his peace of mind. Mahler’s music provides us with the only indication that his inner life underwent a change at that time.” Such commentary ignores the principal biographical event in Mahler’s life during the time immediately preceding the composition of the symphonies nos. 5–7—he fell in love, a condition not unknown to alter a person’s life.

In November 1901, Mahler met Alma Schindler, daughter of the painter Emil Jacob Schindler, then 22 and regarded as one of the most beautiful women in Vienna. Mahler was 41. Romance blossomed. They were married in March and were parents by November. Their first summer together (1902) was spent at Maiernigg, Mahler’s country retreat on the Wörthersee in Carinthia in southern Austria, where the Fifth Symphony was composed—he thought of it as “their” music, the first artistic fruit of his married life with Alma. The Sixth Symphony was composed during the two following summers, and the Seventh in 1904–1905. In this trilogy of symphonies occupying the center of his creative life, Mahler seems to have taken inordinate care to demonstrate the mature quality of his thought (he was, after all, nearly twice Alma’s age), and to justify his lofty position in Viennese artistic life. He may well have wanted to create music that would be worthy of the new circle of friends that Alma, the daughter of one of Austria’s finest artists and most distinguished families, had opened to him—Gustav Klimt, Alfred Roller (who became Mahler’s stage designer at the Court Opera), architect Josef Hoffmann and the rest of the cream of cultural Vienna. Since neither Mahler nor Alma explained the great change of compositional style of 1902, the question can never be securely answered. Mahler’s renewed musical language seems too close in time to the vast extension of his social life engendered by his marriage, however, to have been unaffected by it. In an 1897 letter to the conductor Anton Seidl, Mahler himself confirmed the symbiotic relationship of his music and his life: “Only when I experience do I compose—only when I compose do I experience.”

The Seventh Symphony was a product of the happiest years Mahler knew. His career as director of the Vienna Opera was at its apex (in 1904 and 1905, he introduced his highly regarded version of Fidelio, conducted an important production of Don Giovanni with decor by Alfred Roller, and prepared for revivals of Così fan tutte and The Abduction from the Seraglio), his life with Alma was satisfying, his family had grown to include two healthy daughters, and his music was gaining recognition. Just as the Sixth Symphony was being completed at Maiernigg in September 1904, he quickly wrote the two Andantes that were to become the “night music” movements of the Symphony No. 7. His hectic performance and administrative schedule in Vienna during the winter months precluded further work on the new piece. When he returned to Maiernigg the following May, however, “Not a note would come,” he recalled. “I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom....then I tore off to the Dolomites. There I was led the same dance, and at last gave it up and returned home.... I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke, the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head—and in four weeks, the first, third and fifth movements were done.” The Symphony was completed in short score before Mahler returned to Vienna in the autumn; the work was orchestrated, as was his usual method, during daily two-hour sessions before he left for the Opera at 9:00 a.m. The full score was finished early in 1906. It was to be the last work of that halcyon period in Mahler’s life.

Between the completion of the Seventh Symphony in 1906 and its premiere in Prague under the composer’s direction on September 19, 1908, Mahler’s life was turned upside-down. In 1907, three separate shocks befell him that crushed his happiness and hastened his early death at the age of only 50: in March, against the continuing background of budgetary distress, hide-bound conservatism, and muted but pervasive anti-Semitism, Mahler began to feel that his tenure at the Opera had been a failure, and he resigned; three months later, Dr. Friedrich Kovacs of Vienna diagnosed a serious heart condition caused by subacute endocarditis and advised Mahler that he would have to cease all strenuous activity and limit his professional responsibilities if the disease were not to prove rapidly fatal; and, in July, the composer’s beloved four-year-old daughter, Maria, died of scarlet fever and diphtheria. The man who conducted the premiere of the Seventh Symphony was much changed from the man who composed it. Alma recorded that he worked incessantly on revising the score’s orchestration during the long series of rehearsals (some two dozen according to the conductor Otto Klemperer, one of the youthful musicians who clustered devotedly around Mahler and helped with his premieres), and that his stamina and self-confidence seemed particularly taxed by preparations for the performance. “He was torn by doubts,” she wrote. “He avoided the society of his fellow-musicians, which as a rule he eagerly sought, and went to bed immediately after dinner so as to save his energy for the rehearsals.” Though the local orchestra won Mahler’s approval, and the event generated considerable excitement, Alma reported that the piece had only a “succès d’estime.... The Seventh was scarcely understood by the public.” The work was heard again during Mahler’s lifetime, notably in Hamburg, Munich, Amsterdam and Vienna, but it failed to achieve widespread acceptance and came early in its history to be regarded as something of a step-child among the symphonies; it was not heard in the United States until Frederick Stock conducted it in Chicago in 1921.

Philip Barford accused Mahler of “reworking earlier inspirations” in the Seventh Symphony, noting its similarity to the Symphony No. 5 in its five-movement, symmetrical structure, progressive tonality (i.e., ending in a key different from the beginning), and use of an exuberant, brightly colored rondo-finale. The Symphony No. 7, however, is not only different in its emotional progression, but also surpasses the earlier work in the brilliance, innovation, sonority and sheer power of its scoring. It also, according to Burnett James, “points boldly into the future: elements of its scoring, its harmony and its Expressionist ambience lead to where Schoenberg, Berg and Webern were already waiting in the wings and were already moving towards stage center.” Noted conductor and champion of modern music Hermann Scherchen said that the piece gave him his “first whiff of a new artistic feeling, one that marked the transition to Expressionism.”

The first movement, amply endowed with such forward-looking harmonic devices as superimposed fourths and incipient polytonality, is a vast sonata-allegro design prefaced by a stern introduction (led by the tenor tuba) containing motivic germs from which several later themes grow. An embryonic version of the main theme is given by unison trombones, only to be interrupted by another somber proclamation from the tenor tuba. The horns then take over the trombones’ theme to launch the main body of the movement. A sentimental melody, very Viennese in manner, is given by the violins to provide contrast. The center of the movement is occupied by development of motives from the introduction and the main theme, and a thorough examination of the superimposed fourths, both harmonically and melodically. Solos in the bass and tenor trombones and the tenor tuba lead to the recapitulation, initiated by an augmented presentation of the main theme by horns, trombones and cellos.

The Symphony’s three central movements (Nachtmusik I—Scherzo—Nachtmusik II) are grouped together within the massive bulwark of the opening movement and the Rondo-Finale. The Nachtmusik ("Night Music") I, in an unsettled C major-minor tonality, is one of Mahler’s most fantastic inspirations. Burnett James found here “a sense of tattered ghostly armies marching by night, of bugle calls and responses as well as those of birds and beasts; not so much barbarous armies that clash by night, as of remnants of those which have clashed.” Bright dawn does not immediately follow this musical night, however, since the ensuing Scherzo is among the most haunted, spectral and disquieting movements in the symphonic literature. “A spook-like, nocturnal piece,” Mahler’s friend and protégé Bruno Walter called it; Ronald Kinloch Anderson allowed that if the surrounding movements are “night” music, this Scherzo might well be “nightmare” music. “A glimpse of darkness, of the skull beneath the skin with its mocking grimace, of the essential horror,” wrote James. This devil’s waltz of a movement is followed by the delicate Nachtmusik II, whose simplicity, quietude and gentle guitar and mandolin sounds serve to quell the apprehension of the Scherzo and to prepare for the sunburst of the Symphony’s close.

The Rondo-Finale has, with justification, been criticized for a lack of coherence and an uninhibited boisterousness sometimes bordering on the banal. Certainly, it does not achieve the transcendent heights of the end of Second Symphony, or the otherworldliness of the Fourth, or the unmitigated tragedy of the Sixth. In the context of this particular symphony, however, the finale is an appropriate emotional and stylistic closure to the expressive and formal progression circumscribed by the earlier movements, achieving a mood that Paul Stefan said is “on top of a mountain.”

So strongly did the Symphony affect one young admirer at its Viennese premiere in December 1909 (directed by Ferdinand Löwe—Mahler was reluctant to promote his own works in that city) that he wrote the following letter to its composer, who was then conducting at The Metropolitan Opera in New York:

The impressions made on me by the Seventh...are permanent. I am now really and entirely yours. For I had less the feeling of that sensational intensity which excites and lashes one on, which in a word moves the listener in such a way as to make him lose his balance without giving him anything in its place, [than] the impression of perfect repose based on artistic harmony; of something that set me in motion without simply upsetting my center of gravity and leaving me to my fate; that drew me calmly and pleasingly into its orbit.... Which movement did I like the best? Each one! I can make no distinction.... I was in tune to the very end. And it was all so transparently clear to me. In short, I felt so many subtleties of form, and yet could follow a main line throughout. It gave me extraordinary pleasure.

—Arnold Schoenberg

— Dr. Richard E. Rodda