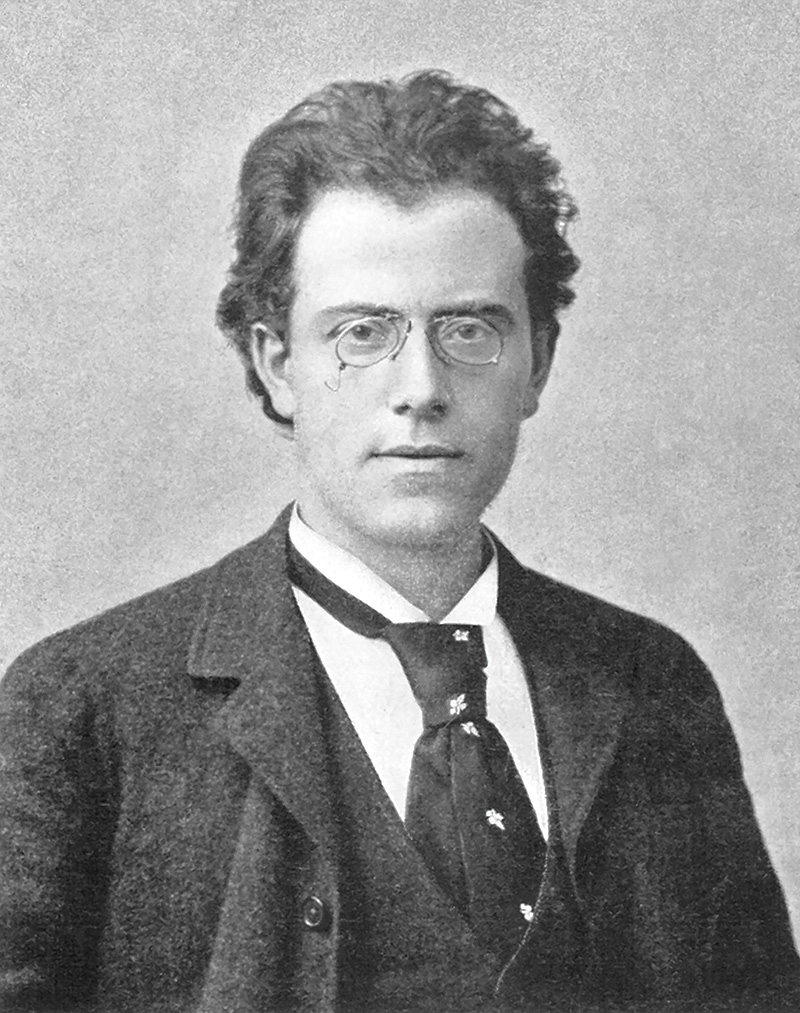

Gustav Mahler

- Born: July 7, 1860, Kalist, Bohemia

- Died: May 18, 1911, Vienna

Symphony No. 8 in E-flat Major, Symphony of a Thousand

- Composed: 1906

- Premiere: September 12, 1910 in Munich, conducted by the composer

- Instrumentation: SATB soloists, SATB double chorus, youth/children’s choruses, 5 flutes (incl. piccolo), piccolo, 4 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 4 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 8 trumpets, 7 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, deep bells, glockenspiel, tam-tam, triangle, 4 harps, celeste, harmonium, organ, piano, mandolin, strings

- May Festival notable performances: First: May 1931, Eugene Goossens conducting (soloists: Jeanette Vreeland, soprano; Editha Fleischer, soprano; Helene Kessing, soprano; Muriel Brunskill, contralto; Eleanor Reynolds, contralto; Dan Gridley, tenor; Fraser Gange, bass; Herbert Gould, bass); May Festival Chorus, Alfred Hartzel, chorusmaster; Conservatory of Music Chorus, John A. Hoffmann, director; St. Lawrence School, J. Alfred Schehl, conductor. Most Recent: May 2014, James Conlon conducting (soloists: Erin Wall, soprano; Tracy Cox, soprano; Amanda Woodbury, soprano; Sara Murphy, mezzo-soprano; Ronnita Nicole Miller, mezzo-soprano; Brandon Jovanovich, tenor; Kristinn Sigmundsson, bass-baritone; Donnie Ray Albert, baritone); May Festival Chorus, Robert Porco, director; Nashville Symphony Chorus, Kelly Corcoran, director; Cincinnati Youth Choir, Robyn Lana, director.

- Duration: approx. 80 minutes

In 1899, Mahler purchased a house and a plot of land at Maiernigg on Lake Wörth in southern Austria as a summer retreat from his strenuous duties as director of the Vienna Opera and as a quiet place to compose. After the 1905–1906 Vienna season, he conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony in Essen on May 27, and then went directly to Maiernigg “with the firm resolution of idling the holiday away and recruiting my strength,” he promised his wife, Alma. Although he had little time for creative work during the winter due to his operatic duties (he orchestrated his short scores from the summer during whatever minutes he could steal from his schedule during those months), he had no plans to undertake a new composition in 1906. Quite unexpectedly (Mahler once said, “I don’t choose what to compose. It chooses me.”), his imagination was seized by the words of the Latin hymn Veni, Creator spiritus, long attributed to Hrabanus Magnentius Maurus (780–856), Archbishop of Mainz, but now conceded to be by an unknown hand. The ancient hymn, Mahler said, “took hold of me and shook me and drove me on for the next eight weeks until my greatest work was done.”

Mahler started composing music for the Veni, Creator spiritus feverishly, but for the words he was depending on his memory and on what proved to be a corrupt edition of the verses. He found the music running unaccountably ahead of the text, and lamented the fact to a philologist friend, who told him that several lines were missing from his version. On July 18th, Mahler hurriedly cabled his Viennese friend, the archeologist Dr. Friederich Löhr, and asked him to locate a reliable edition of the hymn and send it to him with all possible speed. Alma recorded with amazement that “the complete text fit the music exactly. Intuitively he had composed the music for the full strophes!” (Mahler did, however, omit a few words in stanzas five and six.)

Caught in a whirlwind of inspiration, Mahler was possessed of enough audacity to attempt, as a complementary movement to his Veni, Creator Spiritus, a setting of the closing scene from that most sacred icon in all German literature, Goethe’s Faust. Faust had already been the subject of a number of earlier compositions; indeed, Goethe hoped that parts of it would be set to music. Berlioz played fast and loose with the story in his La damnation de Faust (in which he transports the hero to the plains of Hungary for the sole purpose of incorporating his popular Rákóczy March into the score); Liszt was inspired to write a Faust Symphony; Schumann composed Scenes from Goethe’s Faust; Wagner penned a Faust Overture; Gounod made melodrama of Goethe’s soaring verse in his 1859 opera; and Boito conjured up more power than profundity in his 1868 Mefistofele. Mahler’s version would surpass all of these, not only in the enormous forces required for its performance but also in the sweeping, transcendent nature of its vision.

Mahler took as his subject the last scene from Faust, Part II, those paragraphs in which Goethe chose not the death and damnation accorded to the title character in earlier realizations of the story but rather salvation and assumption into the highest universal bliss. The scene is set in rocky gorges inhabited by religious hermits named, in ascending order of divine knowledge, Pater Ecstaticus, Pater Profundis and Doctor Marianus. The spirits of children who died in infancy hover about. Angels bear the soul of Faust to this lofty place. Doctor Marianus hails the appearance of the Virgin (Mater Gloriosa), with whom penitent women intercede for mercy for another penitent, Gretchen. Gretchen is forgiven and charged to lead Faust “to higher spheres.” The Chorus Mysticus sings of the heaven where earth’s imperfections are swept away and the Virgin’s pure love—the “Eternal Feminine”—leads humanity onward.

Just before leaving to conduct The Marriage of Figaro in Salzburg on August 18, 1906, in honor of the 150th anniversary of Mozart’s birth by “Supreme Command” of the Emperor Franz Josef himself, Mahler wrote to the conductor Willem Mengelberg, “I have just finished my Eighth! It is the most important thing I have done so far. And so individual in content and form that I cannot describe it in words. Imagine that the whole universe begins to vibrate and resound. These are no longer human voices, but planets and suns revolving.” Later, Mahler wrote to Alma specifically about his music for Faust: “It is all an allegory to convey something which, whatever form it is given, can never be adequately expressed.... That which draws us by its mystic force, what every created thing, perhaps even the stones, feels with absolute certainty as the center of its being, what Goethe here—again employing an image—calls the ‘Eternal Feminine’—that is to say the resting-place, the goal, in opposition to the striving and struggling towards the goal (the ‘Eternal Masculine’)—you are quite right in calling it the force of love. There are infinite representations and names for it.... Christians call this eternal blessedness [Mahler converted from his paternal Judaism to Christianity before taking the Vienna post in 1897], and I cannot do better than employ this beautiful and sufficient mythology—the most complete conception to which at this epoch of humanity it is possible to attain.”

The realization of such an extraordinary vision required one of the most elaborate aggregations of performers ever required for a musical work (an enormous orchestra, eight soloists and three choirs), and, given Mahler’s own deteriorating health, the press of his new duties at The Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic after resigning from the Vienna Opera in 1907, and the composition of Das Lied von der Erde and the Ninth Symphony, it was some time before he could arrange for the premiere. The impresario Emil Gutmann finally accepted the challenge and scheduled the Eighth Symphony’s first performance for Munich in September 1910. Since Mahler was engaged in New York throughout the winter months, his protégé Bruno Walter was entrusted with the preparations for the concert, including the selection and coaching of soloists and choristers and the direction of preliminary rehearsals.

Gutmann advertised the production as the “Symphony of a Thousand” (Mahler was worried that it would deteriorate into “a Barnum and Bailey show”) and enlisted 858 singers and 171 instrumentalists. Preparations went ahead for the performances on Monday and Tuesday, September 12 and 13, in Munich’s new Musikfesthalle with meticulous attention to detail: Mahler consulted Alfred Roller, his designer at the Vienna Opera, on the most striking visual and acoustical deployment for his vast musical forces; many levels of lighting were tried before the most effective one was chosen; the program booklet went through constant revision; the passing streetcars were instructed not to sound their bells during the concerts. Reports unanimously tell of the awe that Mahler, as both conductor and composer, inspired first in his performers and then in his audiences. Many of the leading intellectual figures of the day attended, including Klemperer, Stokowski (who created a sensation in Philadelphia when he gave the American premiere of the Eighth Symphony six years later), Webern, Casella, Stefan Zweig, Siegfried Wagner, Max Reinhardt, and many others. Thomas Mann was so moved by the performance that he sent Mahler a copy of his latest novel, Königliche Hoheit (“Royal Highness”), inscribed to “the man who, as I believe, expresses the art and time in its most profound and most sacred form.” The event was Mahler’s only unmitigated acclamation as a composer during his entire life. It was also the last time he conducted in Europe and the last time he led one of his own works anywhere. Nine months later, he was dead of a streptococcus infection that stilled his already weakened heart.

The two large parts in which Mahler disposed the huge panorama of his Eighth Symphony contrast in language, form and musical style. Part I, Veni, Creator Spiritus, originally a hymn used in the Roman Catholic liturgy at Pentecost, the celebration of the descent of the Holy Ghost upon the followers of Jesus Christ after His resurrection, asks the Divinity to “kindle our senses with light, pour Thy love into our hearts.” Mahler’s logical and grandiloquent reply in Part II to this invocation is the scene from Faust, which he relates musically to the Veni, Creator Spiritus movement through the recurrence of certain motives, the most triumphant of which is the transformed main theme of the first movement pealed forth by the supplementary brass instruments in the Symphony’s closing pages. “Despite the vastness of the work,” wrote Egon Gartenberg in his study of the composer, “it is a structural marvel, surprisingly compact and integrated. Aspects of three pronounced musical periods are evident: the structure of the Viennese Classics [Part I is in sonata-allegro form]; the color and glow of the Romantic age; and at the high point of symphonic drama Mahler reaches back to Bruckner and even further back to the splendor and spirit of the Baroque. It is the interplay among these diverse influences that makes Mahler’s Eighth Symphony a milestone in its time and a highlight of his creative life.... All are integrated in one musical masterpiece and heightened in intensity by Mahler’s grandiose vision.”

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda