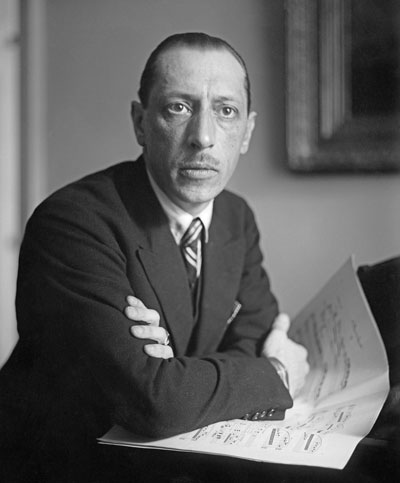

Igor Stravinsky

- Born: June 17, 1882, Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg

- Died: April 6, 1971, New York City

Le Sacre du printemps (“The Rite of Spring”)

- Composed: 1910–13, revised in 1921 and 1943

- Premiere: May 29, 1913 in Paris, Pierre Monteux conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), piccolo, alto flute, 4 oboes (incl. English horn), English horn, 3 clarinets (incl. bass clarinet), bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 4 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), contrabassoon, 8 horns (incl. 2 Wagner tubas), piccolo trumpet in D, 4 trumpets in C (incl. E-flat bass trumpet), 3 trombones, 2 tubas, 2 timpani, antique cymbals, bass drum, crash cymbals, guiro, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: April 1936, Eugene Goossens conducting. Most Recent: September 2018, Louis Langrée conducting. Other: November 1940, Igor Stravinsky conducting; November 1987, Iván Fischer conducting.

- Duration: approx. 33 minutes

Stravinsky’s conception for The Rite of Spring, one of the most influential musical works of the 20th century, came to him as he was finishing The Firebird in 1910. He had a vision of “a solemn pagan rite; wise elders, seated in a circle, watching a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of spring.” Stravinsky knew that Nicholas Roerich, a friend who was an archeologist and an authority on the ancient Slavs, would be interested in his idea, and he mentioned it to him. Stravinsky also shared the vision with Serge Diaghilev, impresario of the Ballets Russes, the company that had commissioned The Firebird. All three men were excited by the possibilities of the project—Diaghilev promised a production and encouraged Stravinsky to begin work immediately. Having just nearly exhausted himself with the rigors of completing and staging The Firebird, however, Stravinsky decided to compose a Konzertstück for piano and orchestra as relaxation before undertaking his pagan ballet. This little “concert piece,” however, grew into the ballet Petrushka, and he could not return to The Rite until the summer of 1911.

“What I was trying to convey in The Rite,” said Stravinsky, “was the surge of spring, the magnificent upsurge of nature reborn.” Inspired by childhood memories of the coming of spring to Russia (“which seemed to begin in an hour and was like the whole earth cracking,” he remembered), he worked with Roerich to devise a libretto that would, in Roerich’s words, “present a number of scenes of earthly joy and celestial triumph as understood by the ancient Slavs.” Stravinsky labored feverishly on the score through the winter of 1911-1912, realizing by that time that he was composing an important piece in a startling new style. “I was guided by no system whatever in The Rite of Spring,” he wrote. “Very little immediate tradition lies behind it. [Debussy was the only influence he admitted.] I had only my ear to help me. I heard, and I wrote what I heard. I am the vessel through which The Rite passed.”

Diaghilev scheduled the premiere for May 1913, and Nijinsky was chosen to do the choreography. Stravinsky, however, objected to Nijinsky’s selection because of the dancer’s inexperience as a choreographer and his lack of understanding of the technical aspects of the music, but preparations were begun and continued through more than 120 rehearsals. Pierre Monteux drilled the orchestra to the point of anxious readiness. The guests invited to the final dress rehearsal seemed to appreciate the striking modernity of the work but gave no hint of the donnybrook that was to roar through the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées at the public premiere on May 29, driven in equal parts by the iconoclastic angular choreography and the revolutionary music. Almost as soon as the curtain rose, a riot broke out the likes of which had not been inspired by a piece of music since Nero’s song of antiquity. Shouts, catcalls, whistles, even fisticuffs, grew so menacing that often the orchestra could not be heard. Diaghilev flashed the house lights on and off in a vain attempt to restore order; Nijinsky, when he was not on stage, pounded wildly on the scenery with his fists to keep the dancers together; Stravinsky ran out of the auditorium (“as angry as I have ever been in my life”) and spent most of the evening backstage pacing in the wings. Somehow Monteux (“cool as a crocodile,” recalled Stravinsky) guided the performance through to the end. Puccini thought The Rite “might be the creation of a madman” and the critic of The New York Sun nominated the composer as “the cave man of music.” No one could deny, however, the ferocious, overwhelming power of the music, and when audiences began to listen to the work on its own revolutionary terms, they could not help but be swept away by its awesome and wonderful maelstrom of exquisitely executed sound. Within a year of its stage premiere, Koussevitzky in Russia and Monteux in Paris had conducted concert performances of The Rite, and the true value of the work began to be recognized. A somewhat edited version of the score in Fantasia, Disney’s animated cartoon movie of 1938, brought the music to a wide audience, and its position in the orchestral repertory was soon secured.

E.W. White, in his exemplary study of the composer, summarized the salient stylistic features of The Rite of Spring in his exemplary study of the life and works of Stravinsky: “A tremendous internal tension is set up in the score between the simplicity of the thematic material and the discordant complexity of the harmonic texture. This is exacerbated by the instrumentation, highly sophisticated means being employed to get a deliberately primitive effect.” The melodic material is often simple and contained within a range of four or five diatonic steps. The score is filled with sharp, often brutal dissonance piled upon the simple melodies and with galvanic rhythms, which the critic Dame Edith Sitwell described as “the beginning of energy, the enormous and terrible shaping of the visible and invisible world through movement.” Stravinsky created the work’s rhythmic electricity with two compositional techniques: powerful, uneven groupings of beats with irregular accents or meters; and short ostinato (i.e., repeated) rhythms. This latter device charges much of the score with a primitive power unlike any music written before it. The most stunning evidence of the dynamism this technique engenders occurs where an ostinato-based wall of sound suddenly collapses into a void of roaring silence. Such abrupt stops are the psychological equivalent of a head-on collision. The Rite of Spring is a work of consummate artistry and bold, innovative vision that won for Stravinsky a place among the greatest creative artists in the history of music.

Robert Lawrence, in The Victor Book of Ballet, provided the following summary of the stage action:

Dealing with archaic Russian tribes and their worship of the gods of the harvest and fertility, The Rite of Spring falls into two separate, yet mutually interdependent, parts—the Adoration of the Earth and the Sacrifice. These primitive peoples assemble for their yearly ceremonies, play their traditional games, and finally select a virgin to be sacrificed to the gods of Spring so that the crops and tribes may flourish.

There is a prelude in which the composer evokes the primitive past, when man was in intimate contact with nature. A soft bassoon solo, played high on the instrument to produce a strange tone quality, opens the work—like an immemorial chant heard far off. The curtain rises on a savage daylight picture of an ancient land. Insistent, barbaric rhythms are heard in the orchestra. A group of adolescents appears, and dance until other members of the tribe enter. Then the full round of ceremonies gets under way: a mock abduction, games of the rival tribes, the procession of the Sage, and the thunderous dance of the Earth. The curtain falls, and the orchestra plays a soft interlude representing the pagan night.

Soon the tribal meeting place is seen again. This time, it is dark and the adolescents circle mysteriously in preparation for the choice of the virgin to be sacrificed to the gods. Suddenly their dance is interrupted, and one of the girls who has taken part is marked for the tribal offering. The others begin a wild orgy glorifying the Chosen One and call on the shades of their ancestors. Finally the supreme moment of the ceremony arrives: the ordeal of the Chosen One. It is the maiden’s duty to dance until she perishes from exhaustion. Throughout the dance, the music keeps gathering power through the element of frenzied repetition until finally it spins like a top on its own axis, and ends with a crash as the Maiden dies.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda