Leonard Bernstein

Jack_Mitchell_400x513.jpg)

- Born: August 25, 1918, Lawrence, Massachusetts

- Died: October 14, 1990, New York City

Overture to Candide

- Composed: Completed in August 1956

- Premiere: October 29, 1956, in its first preview at the Colonial Theatre in Boston; the show reached Broadway on December 1 of that year, at the Martin Beck Theatre.

- Instrumentation: (symphonic version played here): 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drums, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, tenor drum, triangle, xylophone, harp, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: January 1962, Haig Yaghjian conducting. Most Recent: October 2017, Louis Langrée conducting. Other: European Tour in 2017, Louis Langrée conducting; Asian Tour in 2009, Paavo Järvi conducting; European Tour in 2001, Jesús López Cobos conducting; European Tour in 1969, Erich Kunzel conducting.

- Duration: approx. 5 minutes

The story of Leonard Bernstein’s musical comedy—or operetta, or opera—Candide is convoluted and, in the end, rather unhappy—an unfortunate situation for a work whose music and lyrics are overwhelmingly ebullient and madcap. Voltaire is to blame for the whole affair, since it was his novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme (1759) that so captivated Bernstein that he struggled for more than three decades to find the right way to translate it for the musical stage.

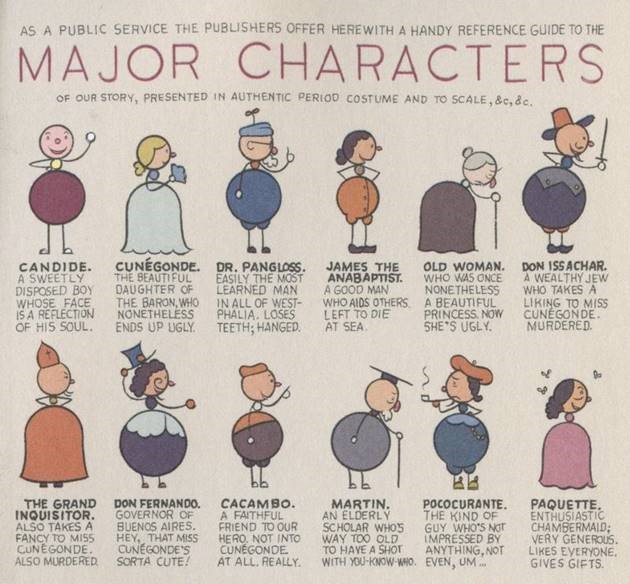

To Voltaire we owe the tale of the wide-eyed hero Candide, whose trips to distant points of the globe invariably turn into dismal misadventures, much though he may be assured by his idealistic tutor, Doctor Pangloss, that everything is for the best. He wrote his novella in the span of three weeks, as a charming but persuasive rebuttal to the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz’s metaphysical assertion that “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds,” a necessary consequence of God being a benevolent deity. Voltaire, however, saw bad things happening all around, including such contemporary occurrences as the Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 (which may have killed up to 100,000 people) and the Seven Years’ War (1756–63, which was leaving bodies strewn on battlefields throughout Europe). The whole idea struck Voltaire as palpably absurd. How does blatant violence fit into Leibnitz’s contention?, he asked. What about shipwrecks? What about the Spanish Inquisition? Candide has to deal with them all in the course of this tale, and by the time he gets back to his native Westphalia he has become a wiser, if more cynical, young man, intent on finding happiness where he can, come what may, and content in just making his garden grow. [First page of 1762 English edition of Voltaire’s Candide]

In the fall of 1953, Lillian Hellman suggested the idea of collaborating with Bernstein on a stage work based on Candide, after an earlier collaboration they had flirted with, on the subject of Eva Perón, had failed to take root. By January 1954, Bernstein was firmly committed to the project, which he initially envisioned as a full-scale three-act opera. Hellman began fashioning Voltaire’s volume into a book for the show, and John Latouche and Richard Wilbur were enlisted to pen the lyrics, although Hellman, Dorothy Parker and Bernstein himself all added further contributions to the script. Candide opened in New York on December 1, 1956 and played for 73 performances at the Martin Beck Theatre—which is to say, long enough to have proved in some measure respectable (and certainly long enough to pique the interest of many sophisticated music lovers), but not long enough to be considered a success by any stretch of Broadway’s imagination.

In the course of later emendations, Candide was transformed considerably. Hellman did not allow her book—neither her words nor the locales she specified—to be used for the 1973 version staged by Hal Prince at the Chelsea Theatre Center. So, on that occasion, a new libretto, reduced to a single act from the original two, was created by Hugh Wheeler, with Stephen Sondheim joining Wilbur, Latouche and Bernstein on the list of the show’s lyricists; unfortunately, some marvelous musical numbers needed to be omitted for this incarnation of the show. Permutations, combinations and revisions of either or both of those two versions charted Candide’s uncertain history, some emphasizing the score’s operatic elements, others its musical comedy streak. Bernstein was directly involved in at least seven versions of Candide, none of which proved definitive, although each had his blessing at least provisionally. In 1989, the composer led a concert performance in London—in a version happily preserved on recordings—that stands as his last sign-off on the opera that had eluded him for 33 years.

But through all the turmoil, the Candide Overture remained essentially untouched. Why change it? From the outset it was popular, a perfect piece of bubbling optimism and knowing skepticism. In his Overture, Bernstein had achieved the flavor he seems to have sought for the rest of the piece. In 1956, Bernstein scaled up the Overture’s orchestration for a full symphony orchestra—this was the only alteration effected on this piece—and in this guise he introduced it as a standalone work with the New York Philharmonic on January 26, 1957. Within two years it would be played by nearly a hundred orchestras, rapidly becoming his most frequently performed symphonic composition.

The Overture prefigures the show by drawing principally on two vocal melodies that are prominent in the stage work. Following some can-can material and a theme that, in the show, occurs at the destruction of Candide’s native Westphalia, we hear a tender (though swiftly flowing) tune that will later resurface as the love duet “O Happy We,” sung by Candide and his girlfriend, Cunegonde. [Barbara Cook and Richard Rounseville sing “Oh, Happy We,” from the original cast album] Curiously, Bernstein had originally intended “Oh, Happy We” as a duet for the characters of Tony and Maria to sing in another show-operetta-opera that was gestating at the same time—but West Side Story is a different matter altogether, and the considerable trading off of material between those two very different works is a subject best saved for another time. Near the Overture’s end, after all manner of musical jokes, Bernstein tips his hat to Rossini and has the orchestra repeat a little tune over and over, growing ever louder. The motif he selects for this honor is extracted from Cunegonde’s aria “Glitter and Be Gay,” which was interpreted in the original production by the indelible Barbara Cook. [Barbara Cook sings “Glitter and Be Gay,” from the original cast album] Separated from Candide by various disasters and believing that he has died, Cunegonde is getting by in Paris when she sings this aria, sharing her amorous favors with influential men, taking consolation in beautiful jewelry.

—James M. Keller

* Portions of the Bernstein notes appeared previously in the programs of the New York Philharmonic and San Francisco Symphony and are used with permission. James M. Keller is in his 24th year as Program Annotator of the San Francisco Symphony and was formerly Program Annotator of the New York Philharmonic and a staff writer-editor at The New Yorker. The author of Chamber Music: A Listener’s Guide (Oxford University Press), he is writing a sequel volume about piano music.