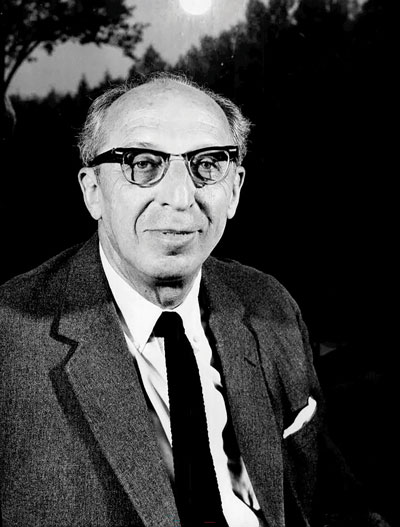

Aaron Copland

- Born: November 14, 1900, Brooklyn, New York

- Died: December 2, 1990, North Tarrytown, New York

Lincoln Portrait

- Composed: 1942, on commission from conductor Andre Kostelanetz; text arranged by Copland from words by Abraham Lincoln.

- Premiere: May 14, 1942 by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Andre Kostelanetz conducting; William Adams, narrator

- Instrumentation: narrator, 2 flutes (incl. 2 piccolos), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, sleigh bells, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, xylophone, harp, celeste, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: World premiere, May 1942, Andre Kostelanetz conducting; William Adams, narrator (part of the Pension Fund Benefit Concert). First Subscription: February 1948, Thor Johnson conducting; Peter Grant, narrator. Most Recent: Fall 2017 European Tour, Louis Langrée conducting and Leilani Barrett, narrator; April 1976, Aaron Copland conducting and Ray Middleton narrator. Recording: Hallowed Ground (2014), Louis Langrée conducting; Dr. Maya Angelou, narrator.

- Duration: approx. 14 minutes

“This Gallery of Musical Portraits is a direct result of the momentous events of December, 1941. In the weeks that followed our entrance into the war I gave a great deal of thought to the manner in which music could be employed to mirror the magnificent spirit of our country.” —Andre Kostelanetz

Just as the United States became actively involved in World War II, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra gave auspicious premieres of two consequential works by the “Dean of American Music,” Aaron Copland. One is among Copland’s most familiar, beloved and most frequently performed, Fanfare for the Common Man (1943). Eugene Goossens commissioned the Fanfare as one of 18 curtain raisers by various composers that opened Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra concerts during the 1942-43 season, all meant to rally support for American war efforts. The other major work that came out of this moment is Lincoln Portrait (1942), a patriotic meditation on American ideals embodied by the country’s 16th president, Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln Portrait premiered May 14, 1942 on a benefit program for the Orchestra’s pension fund given by Andre Kostelanetz, the piece’s commissioner and dedicatee, and his wife, the soprano Lily Pons. The concert, dubbed a “Gallery of Musical Portraits,” included Lincoln Portrait as one part of a triptych of world premieres, alongside Jerome Kern’s Mark Twain: Portrait for Orchestra (also called Mark Twain Suite) and Virgil Thomson’s The Mayor LaGuardia Waltzes, inspired by New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and journalist Dorothy Thompson. Copland originally planned to compose an ode to the poet Walt Whitman, but Kostelanetz persuaded him to choose again to avoid encroaching on Kern’s effort. Copland devised his text himself, incorporating sections from Lincoln’s December 1862 second annual address to Congress (“Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history.” “The dogmas of the quiet past…”), the seventh installment in Alton, Illinois of the famed Lincoln-Douglas Debates (“It is the eternal struggle between two principles…”), Lincoln’s August 1, 1858 “Definition of Democracy” (“As I would not be a slave, I would not be a master.”), and the 1863 Gettysburg Address (“…from these honored dead, we take increased devotion…”). Descriptions of Lincoln’s appearance, persona and background interleave the quotations, making an explicit connection between the man and the principles for which he stood, as full a portrait as one can give in a short time. To some extent, Copland joined in a growing interest in Lincoln that swelled during the first half of the 20th century, which may have informed his choice.

The piece begins with a slow introduction, delicately coaxing out single members of the orchestra who pass to one another the same long-short-long, three-note musical idea. The full orchestra soon joins for a full-throated fanfare built on the same fragment. The way clears and a solo clarinet brings out the elegiac ballad tune, “Springfield Mountain,” which is immediately echoed by other woodwinds and a solo trumpet. But staid moods reflecting Lincoln’s restrained image do not last long—the full orchestra breaks through with variations on Stephen Foster’s “Camptown Races,” although only in snippets. Copland intended the ensuing cacophonous layering of “Springfield” and “Camptown” to convey a wide range of human experience, a setup for the nuances of the narrated texts that follow. A slowing recall of “Springfield” ushers in the narrator, whose words the orchestra underscores and underlines in tone and intensity—weightier music complements quotations of Lincoln’s orations, simpler textures carry the biographical trimmings. Perhaps the most poignant moment of the entire piece is that which brings about the piece’s climactic ending: a solo trumpet deferentially summons “Springfield” once more for the august words of the Gettysburg Address.

Lincoln Portrait most strongly represents what many think of as Copland’s Americanist style. This style is identified closely with Fanfare for the Common Man and Lincoln Portrait, but also the famous ballets Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942) and Appalachian Spring (1943-44), the film score for Of Mice and Men (1939), as well as the later midwestern Gothic opera The Tender Land (1952-54). Copland’s career is often broken into discrete phases: early jazz to the late 1920s, then a turn toward the abstract before Americana populism in the 30s to early 50s, then modernism thereafter. More realistically, though, Copland moved fluidly between styles that correspond to these categories. The Clarinet Concerto (1947-48), for instance, was written after Copland’s “jazz period” but incorporates elements of swing and was premiered by the great Benny Goodman. Keeping this in mind lends some explanation for the variety of Lincoln Portrait’s moods and tensions, which Copland intended to resound its complicated themes on a deep level.

As musicologist Elizabeth Crist has written, Copland’s compositions from the 1930s and 40s reflect his ongoing alignment with Popular Front political causes. This manifests most clearly in his embrace of cultural pan-Americanism, with musical inspiration drawn from the United States and from Central and South America. The use of folk song quotation in El Salón México (1932-6), for instance, resurfaces in the opening minutes of Lincoln Portrait and is at the heart of the utopian ethos of Copland’s arguably most famous piece, Appalachian Spring. In all cases, Copland found inspiration in an association of folk and popular music with everyday people, an enduring interest that guided his compositional style, which he hoped would invite a wide listenership.

Years passed before Lincoln Portrait found its place in the regularly performed repertoire, with critics and musicians initially wavering on its merits. The influential American composer William Schuman helped champion the piece early on, though, and by the American Bicentennial of 1976, it had become an emblematic thread in the fabric of American concert music. Now, it is as much a staple among American orchestras as any of Copland’s music, popular in part due to its practicality and accessibility for musician and non-musician alike to perform the narration. In this, the piece takes up the legacy practices of elocution and declamation, that is, speaking over musical accompaniment, popular especially among women from the 19th century into the 20th. An impressive list of prominent individuals have declaimed for Copland’s piece, including several stars of classical Hollywood cinema, numerous politicians and a vast array of locally and internationally famous media personalities. The important American contralto Marian Anderson performed the piece on multiple occasions beginning in the 1960s, and Coretta Scott King (a New England Conservatory trained singer and pianist) presented it with the National Symphony Orchestra the year after her husband’s assassination. Copland hand-selected Henry Fonda for a 1971 recording with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer. While an ill-fated recording was made by the same orchestra with former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher speaking the text in 1992, a more successful one was made that year by Leonard Slatkin and the St. Louis Symphony with General “Stormin’” Norman Schwarzkopf narrating. Carl Sandburg, Eleanor Roosevelt and many other luminaries also performed the piece, in addition to Copland himself. Over the course of his performance career with the piece, Kostelanetz often asked his narrators to sign his conducting score, an impressive record of the piece’s reputation.

Still, even after it had begun to gain wider appreciation, the piece was not exempt from controversy. Much as he resisted accusations, the 1950s greeted Copland with McCarthyist anti-communist inquiries due to the composer’s political beliefs. Plans for a performance of Lincoln Portrait in celebration of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1953 presidential inauguration were scuttled by Illinois Representative Fred Busbey over Copland’s earlier political sympathies. Despite protests and statements on Copland’s behalf from musical colleagues and advocates of free speech, the performance remained canceled. The composer was not entirely deflated by the incident, later reflecting humorously that he was happy the piece had been canceled for political reasons and not aesthetic ones. He went on to compose more works with a political voice, including the similarly-constructed Preamble for a Solemn Occasion (1949) for orchestra and speaker to commemorate the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as the Canticle of Freedom (1955) for orchestra and amateur chorus that, as Howard Pollack has written, “stared McCarthyism squarely in the face” by invoking Scottish struggles for liberty.

Since its premiere performance with Kostelanetz in 1942, Lincoln Portrait has been a mainstay for the city of Cincinnati. Conductor Erich Kunzel regularly brought the work to audiences, often as part of the Cincinnati Pops’ Independence Day festivities at Riverbend Music Center. A varied list of narrators has presented the work to Cincinnatians, including Katharine Hepburn (1987), Bryant Gumbel (1992) and Dr. Maya Angelou (2013 on Louis Langrée’s inaugural concert). And the piece has provided a link between the city’s musical and civic institutions, bringing a spate of local and state politicians and even members of the Cincinnati Bengals to perform. (A longer list of performers may be found here.)

—Dr. Jacques Dupuis