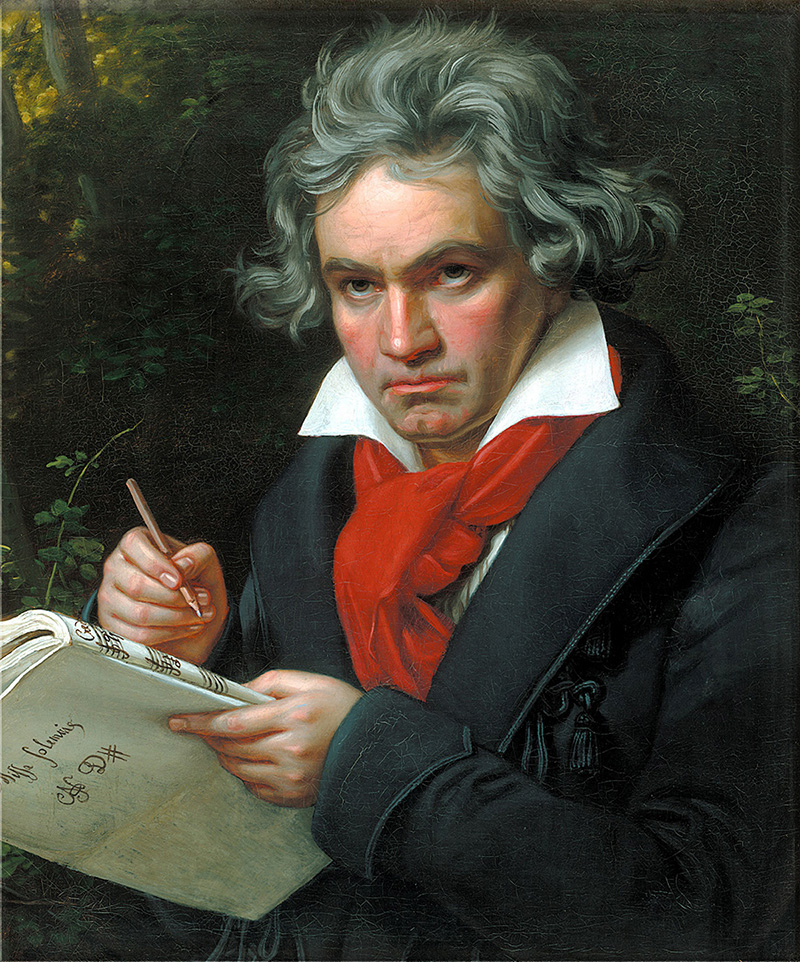

Ludwig van Beethoven

- Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

- Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Concerto No. 4 in G Major for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 58

- Composed: 1804–06

- Premiere: Beethoven included the Concerto No. 4 in his Akademie program of December 22, 1808, but it had first been heard at a private concert on March 5, 1807 at the palace of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz in Vienna, with the composer as soloist.

- Instrumentation: solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: January 1905, conducted by Frank Van der Stucken with pianist Josef Hofmann. Most Recent: September 2021 as part of MusicNOW, Louis Langrée conducting and Daniil Trifonov, pianist. Other: February/March 2020 as part of the Beethoven Akademie concert with Louis Langrée conducting and pianist Inon Barnatan. Notable pianists: Artur Schnable, Arthur Rubinstein, Claudio Arrau, Glenn Gould, Emil Gilels, André Watts, Awadagin Pratt and Hélène Grimaud.

- Duration: approx. 34 minutes

Music in the Time of War

The Napoleonic juggernaut twice overran the city of Vienna. The first occupation began on November 13, 1805, less than a month after the Austrian armies had been soundly trounced by the French legions at the Battle of Ulm on October 20th. Though their entry into Vienna was peaceful, the Viennese had to pay dearly for the earlier defeat in punishing taxes, restricted freedoms and inadequate food supplies. On December 28th, following Napoleon’s fearsome victory at Austerlitz that forced the Austrian government into capitulation, the Little General left Vienna. He returned in May 1809, this time with cannon and cavalry sufficient to subdue the city by force, creating conditions that were worse than those during the previous occupation. As part of his booty and in an attempt to ally the royal houses of France and Austria, Napoleon married Marie Louise, the 18-year-old daughter of Austrian Emperor Franz. She became the successor to his first wife, Josephine, whom he divorced because she was unable to bear a child. It was to be five years—1814—before the Corsican was finally defeated and Emperor Franz returned to Vienna, riding triumphantly through the streets of the city on a huge, white Lipizzaner.

Such soul-troubling times would seem to be antithetical to the production of great art, yet for Beethoven, that ferocious libertarian, those years were the most productive of his life. Hardly had he begun one work before another appeared on his desk, and his friends recalled that he labored on several scores simultaneously during this period. Sketches for many of the works appear intertwined in his notebooks, and an exact chronology for most of the works from 1805 to 1810 is impossible. So close were the dates of completion of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, for example, that their numbers were reversed when they were given their premieres on the same giant concert. Between Fidelio, which was in its last week of rehearsal when Napoleon entered Vienna in 1805, and the music for Egmont, finished shortly after the second invasion, Beethoven composed the following major works: Piano Sonata, Op. 57 (“Appassionata”); Violin Concerto; Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos; three Quartets of Op. 59; Leonore Overture No. 3; Coriolan Overture; Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Symphonies; two Piano Trios (Op. 70); Piano Sonata, Op. 81a (“Les Adieux”); and many smaller songs, chamber works, and piano compositions. It is a stunning record of accomplishment virtually unmatched in the entire history of music.

“I Sat in My Place Without Moving a Muscle”

The Fourth Concerto was one of the projects of the Napoleonic years, and it seems to have been composed simultaneously with the Fifth Symphony. The two are even related in their use of a basic rhythmic motive—three short notes followed by an accented note—and may have germinated from the same conceptual seed, though with vastly different results. While almost nothing is known of the composition of the Concerto, its early performance history is well documented. Beethoven first played it “before a very select audience which had subscribed considerable amounts for the benefit of the author,” according to one contemporary report. The private event took place at the Viennese palace of Prince Lobkowitz, who returned to the city shortly after Napoleon evacuated in 1805. He promoted two private concerts in March 1806 of music exclusively by Beethoven, and presented the composer with all the proceeds, a refutation of the myth that Beethoven was not appreciated in his own time. An account of the elegant event in the appropriately titled Journal des Luxus was typical of many reviews Beethoven received during his life. The writer noted his “wealth of ideas, bold originality, and abundance of power, the special merits of his muse, which were clearly present in these concerts. But some hearers blamed the neglect of a noble simplicity and a too fertile profusion of ideas, which, because of their quantity, are not always sufficiently fused and elaborated; hence their effect is frequently that of an unpolished diamond.”

Because opportunities for public concerts were so few during those troubled times, Beethoven was unable to perform the Concerto in public until the Akademie concert December 22, 1808, nearly two years after its private premiere. Reports on the quality of Beethoven’s playing at the time differed. J.F. Reichardt wrote, “He truly sang on his instrument with a profound feeling of melancholy that pervaded me, too.” The composer and violinist Ludwig Spohr, however, commented, “It was by no means an enjoyment [to hear him], for, in the first place, the piano was woefully out of tune, which, however, troubled Beethoven little for he could hear nothing of it; and, secondly, of the former so-much-admired excellence of the virtuoso scarcely anything was left, in consequence of his total deafness.... I felt moved with the deepest sorrow at so hard a destiny.” The Fourth Concerto was consistently neglected in the years following its creation in favor of the Third and Fifth Concertos. After Beethoven’s two performances, it was not heard again until Felix Mendelssohn played and conducted the work with his Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra on November 3, 1836. Robert Schumann, who was at that revival, wrote, “I have received a pleasure from it such as I have never enjoyed, and I sat in my place without moving a muscle or even breathing—afraid of making the least noise.”

The Piano Enters the Romantic Age

Of the nature of the Fourth Concerto, Milton Cross wrote, “[Here] the piano concerto once and for all shakes itself loose from the 18th century. Virtuosity no longer concerns Beethoven at all; his artistic aim here, as in his symphonies and quartets, is the expression of deeply poetic and introspective thoughts.” The mood is established immediately at the outset of the work by a hushed, prefatory phrase for the soloist. The form of the movement, vast yet intimate, begins to unfold with the ensuing orchestral introduction, which presents the rich thematic material: the pregnant main theme, with its small intervals and repeated notes; the secondary themes—a melancholy strain with an arch shape and a grand melody with wide leaps; and a closing theme of descending scales. The soloist re-enters to enrich the themes with elaborate figurations. The central development section is haunted by the rhythmic figuration of the main theme (three short notes and an accented note). The recapitulation returns the themes, and allows an opportunity for a cadenza (Beethoven composed two for this movement) before the coda, a series of glistening scales and chords that bring the movement to a joyous close.

The second movement, “one of the most original and imaginative things that ever fell from the pen of Beethoven or any other musician,” according to Sir George Grove, starkly opposes two musical forces—the stern, unison summons of the strings and the gentle, touching replies of the piano. Franz Liszt compared this music to Orpheus taming the Furies, and the simile is warranted, since both Liszt and Beethoven traced their visions to the magnificent scene in Gluck’s Orfeo where Orpheus’ music charms the very fiends of Hell. In the Concerto, the strings are eventually subdued by the entreaties of the piano, which then gives forth a wistful little song filled with quivering trills. After only the briefest pause, a high-spirited and long-limbed rondo-finale is launched by the strings to bring this Concerto, one of Beethoven’s greatest compositions, to a stirring close.

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda