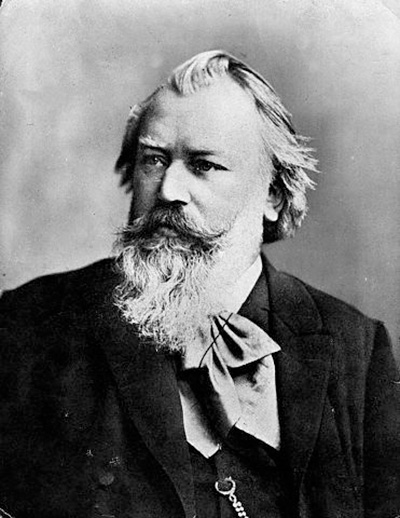

Johannes Brahms

- Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

- Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

String Quartet No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 51

- Composed: 1873

- Premiere: December 11, 1873 in Vienna

- Duration: approx. 34 minutes

“It is not hard to compose, but it is fantastically difficult to leave the superfluous notes under the table,” Johannes Brahms famously complained to his friend, Theodor Billroth, while working on his string quartets Opus 51. Previous generations of musicians had usually composed specific works for specific occasions under tight deadlines; Brahms felt no such pressure. Thus, he took nearly 20 years to publish his first, the String Quartet No. 1 in C Minor. The genre had become a psychological hurdle for him—in part because of the high bar set by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven—resulting in his destroying at least 20 false starts before finally publishing his first two quartets in 1873. According to the composer’s friend, Max Kalbeck, Brahms had even insisted on hearing a full play-through in private before he was willing to submit them to public scrutiny.

Later musicians saw these quartets as central to understanding Brahms’ musical language. They are the cornerstone of Arnold Schönberg’s famous essay, Brahms, the Progressive, in which Schönberg identifies a single short motif in the opening movement. From this motif Brahms generated all of the other themes through augmentation and inversion, techniques which, ironically, are more popularly associated with Schönberg than Brahms. Such intellectual exercise may not be necessary for the listener to enjoy the works, but as musicologist Heinrich Reimann asserted, “Brahms’s quartets have often been criticized for going beyond what four individual instruments can achieve in terms of power and sonority…yet he offers rich rewards to those who follow him along this arduous path, whether they be practicing artists or listening laymen.”

The opening movement of the C minor quartet seems to anticipate two other great C minor openings: those of his First Symphony and Third Piano Quartet. Indeed, all three works were completed between 1873 and 1876, and all three were the result of the composer’s internal struggle for perfection. The Allegro of the quartet is held together by a meticulous sonata form, perhaps to camouflage its tonal and metric instability. The development passes through several related key areas, arrives at the remote destination of A major, and then pivots back to C minor, where it changes from triple to duple meter before ultimately coming to rest in C major.

Although the second movement is titled “Romanze,” it is more melancholy than amorous. When the gently dotted rhythms shift in an upward dolce gesture from A-flat major to C major, they prepare the listener for the halting triplet “sigh” motive that follows, at once both yearning and agitated. After a harmonic twist into E major, the music winds down, first to pizzicato chords and then to silence, before taking up the sighing theme once again. The movement closes on an afterthought: a fading chord simultaneously plucked and bowed.

The third movement is a scherzo more in form than in character. Its pulsating opening motive in F minor would be suitable as a processional were it not for the occasional bursts of playfulness with the triplet motive that follows. The trio introduces a change not only of meter and key, but of geography: the Teutonic opening theme is supplanted by a thoroughly Austrian Ländler before the return of the processional.

The opening accusation of the final movement ignites a contentious argument of counterpoint that, as with the opening movement, takes the listener into metrical conflict and harmonic uncertainty. Brief moments of reconciliation are short lived before passions flair again. The tempo accelerates, and the music churns to an explosive climax, punctuated with three ponderous final chords.

In its warmth and beauty, in its fire and passion, Brahms’ first quartet seems a quintessential reflection of the self-proclaimed romantic of the 19th-century literary world. It affirms rather than refutes the image of the composer as a misunderstood artist, volatile and vulnerable to all that is subjective, irrational, spontaneous and emotional in his search for the transcendental.

—Dr. Scot Buzza