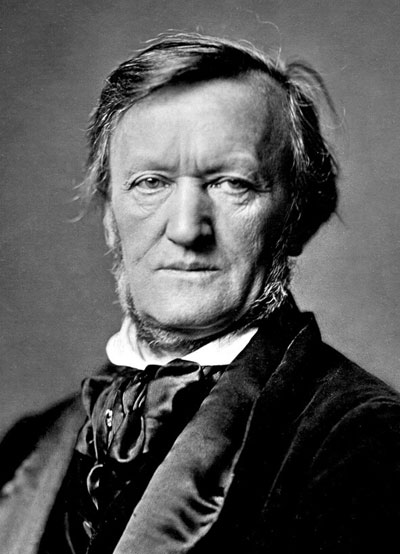

Richard Wagner

- Born: May 22, 1813, Leipzig, Germany

- Died: February 13, 1883, Venice, Italy

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra recognizes Richard Wagner’s antisemitic views and we do not support these views in any way. The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, however, takes our role in the cultural musical, and global ecosystem very seriously, and we understand the immeasurable power that music has to shape lives, emotions and history. Art should be a haven to build empathy, understanding and connection rather than division.

The CSO believes that music lives within us all regardless of who we are or where we come from. We believe that music is a pathway to igniting our passions, discovering what moves us, deepening our curiosity and connecting us to our world and to each other. We also believe that reflecting our community and the world around at every level — on stage, behind-the-scenes, and in neighborhoods throughout the region — is essential to the CSO’s present and future. In order to fulfill these guiding and important principles, we offer the words of important thought leaders, resources to further our knowledge and questions for all of us to ponder.

“We have not forgotten that music is a powerful form of persuasion that does work in the world, a serious art that possesses ethical force and exacts ethical responsibilities…Music does not now exist, nor has it ever existed, in a social vacuum. Its meanings are not self-contained. They are inscribed not only by its creator but by its users.” Richard Taruskin, The New York Times, 1992

From James Bennett II and Max Fine in “Cancel Culture: How We Deal With Wagner in the 21st Century, “we march forward in time not denying its influence, but also not excusing its moral failures, looking for new ways to make it more relevant to society. Because when you know better, you do better.”

Lorin Maazel’s arrangement of Wagner’s Ring Cycle music is a unique tour de force within the repertoire of classical music and is a wonder of technical skill on the part of Maazel, who was able to artfully place the 17 hours of music found within the Ring Cycle into a 75-minute concert work for orchestra only. In the words of Maazel, “I hope that this [work] may bring some of the magic of this monumental work a mite closer and in another aspect to loves of the ‘Ring’ and to a new audience of music-sensitive people.”

We must acknowledge and struggle with the fact that art illuminates some of the ugliest areas of humanity and history, but from within are possibilities for new understandings built upon empathy, humility and reflection.

Please peruse the list of resources and consider the questions below.

Resources:

“Cancel Culture: How We Deal with Wagner in the 21st Century” by James Bennett II and Max Fine, WQXR, 2019.

“As If Music Could Do No Harm” by Alex Ross, The New Yorker, 2014.

“Only Time Will Cover the Taint” by Richard Taruskin, New York Times, 1992.

“The Case for Wagner in Israel” by Alex Ross, The New Yorker, 2012.

“Anti-Semitism: The Controversy over Richard Wagner” by Lili Eylon.

“Reopening the Case of Wagner” by Harvey Gross, The American Scholar, 1968-69.

Judaism in Music by Richard Wagner, translation by William Ashton Ellis, originally published in 1850.

Judaism in Music by Richard Wanger, translation by Edwin Evans.

Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind and His Music by Robert W. Gutman, 1990.

Wagner’s Jews a film by Hilan Warshaw, 2013, which is viewable on medici.tv.

The Nancy and David Wolf Holocaust & Humanity Center

Questions to Consider:

What role does music play in culture and public opinion?

How does understanding the historical context and composer’s background influence your listening and understanding of the composition?

Does music help us to remember and learn lessons from the past?

All art is created by a person(s) within a historical period, how does this impact of effect a piece of art?

With antisemitism on the rise worldwide, how do we individually aid in the elimination of antisemitism?

Der Ring ohne Worte (“The Ring Without Words”) for Orchestra

arr. Maazel (1930-214)

- Composed: 1853–57 and 1869–74

- Premiere: Complete four-opera cycle premiered August 13–17, 1876 at Wagner’s purpose-built Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Germany, conducted by Hans Richter. Arranged in 1987 by Lorin Maazel and premiered in December 1987 by the Berlin Philharmonic, Lorin Maazel conducting.

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), piccolo, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, 8 horns (incl. 4 Wagner tubas, 3 offstage horns), 3 trumpets, bass trumpet, 4 trombones (incl. contrabass trombone), tuba, 2 timpani, 3 anvils, bass drum, cow horn, crash cymbals, glockenspiel, snare drum, tam-tam, triangle, 2 harps, strings

- CSO notable performances: hese are the first CSO performances of The Ring Without Words.

- Duration: approx. 70 minutes

Wagner’s cycle of “music-dramas,” The Ring of the Nibelungen, is unique in the history of art: an ancient mythological tale spread over four interdependent operas; the capstone of Romantic orchestration, harmony and emotional expression; a nodal point in the history of music; and a profound influence on Western thought, art, drama, culture, society and politics.

The vast and complex story of The Ring is told by the singers on stage, but their underlying motivations, as well as the cycle’s dramatic and musical continuity, are entrusted to the orchestra, whose unprecedented scale, power and importance created a sensation throughout the music world when the operas were new and set a precedent that has continued unabated since. Wagner himself, an excellent and pioneering conductor, began the practice of performing orchestral excerpts from The Ring in concert, and instrumental selections from all four of the operas comprising the cycle have remained standard concert fare. These pieces were programmed as separate selections until 1987, when Cleveland-based Telarc International asked Lorin Maazel, a dedicated Wagnerian who had been the first American to conduct the complete Ring at the Festspielhaus (the theater Wagner had specially built in Bayreuth, Germany to stage the cycle), to weave them into a continuous work for a recording with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Maazel set himself some rules in arranging his 70 minutes of orchestra-only excerpts from The Ring’s 17 hours of music:

ONE: The synthesis must be free-flowing (no stops) and chronological, beginning with the first note of Rheingold and finishing with the last chord of Götterdämmerung.

TWO: The transitions must be harmonically and formally justifiable, the pacing contrasts commensurate with the length of the work.

THREE: Most all of the music originally written for orchestra without voice must be used, adding those sections with a vocal line essential to a synthesis but only where the line is either doubled by an orchestral instrument or when it can be reproduced by an instrument.

FOUR: Every note must be Wagner’s own.

The recording of Maazel’s The Ring Without Words was praised upon its release in 1987 and at its public premiere with the Berlin Philharmonic that December, and his arrangement has since been performed frequently across Europe and America.

■ ■ ■

Das Rheingold—the Gold of the River Rhine, the treasure that confers the power to rule the world on its possessor—is the dramatic engine of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen ["Prelude: Primordial Beginnings and The River Rhine"]. In the one-act opera Das Rheingold (composed 1853–54) that opens the cycle, the dwarf Alberich braves the mighty river and steals the golden treasure from its protectors, the Rhinemaidens. Meanwhile, Wotan, chief of the gods, has charged the giants Fafner and Fasolt with building a magnificent new castle as the gods’ abode ["Valhalla, Home of the Gods"]. When the giants agree to accept the Rhine’s golden treasure as payment for their work, Wotan journeys to the subterranean cavern where Alberich has enslaved the race of the Nibelungs, whom he forces to mine and melt gold to add to his hoard ["The Nibelung Dwarves Hammering"]. The smithy Mime, Alberich’s brother, has made a magic helmet from the gold that allows its wearer to assume any form he wishes. Wotan tricks Alberich into changing into a toad, captures both the transformed dwarf and the gold, and returns with them to his mountaintop. When Alberich refuses to take the ring from his finger, Wotan removes it by force. Alberich, infuriated, lays a solemn curse on the ring, that it may bring death to all who own it. The curse begins its devastating effect when the giants struggle over the treasure and Fafner strikes Fasolt a fatal blow. The gods’ new castle—Valhalla—is seen in the distance, beckoning as a haven of safety ["Donner’s Thunderbolt—Storm"]. A rainbow appears as a bridge over the valley to the castle, and the gods enter majestically into their new home while the distant cries of the Rhinemaidens for their lost gold make Wotan apprehensive about the course of future events.

In the time between Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, Wotan has come to believe that only a great hero, one free of knowledge of the past and without fear, would be able to win the Rhinegold and its power for the gods. To set his plan into motion, Wotan goes among mortals and conceives twins—Siegmund and Sieglinde—with a woman of the Volsung tribe. It is they whom he intends to bear the redeeming hero: Siegfried. The life Wotan decrees for Siegmund and Sieglinde is hard. They are violently separated in childhood: Siegmund lives for a time in the forests with his father and then alone and roughly, with frequent battles and much hardship; Sieglinde is married against her will to Hunding, of the savage Neiding tribe.

At the beginning of Die Walküre (1854-56), Siegmund is driven by a violent storm to find shelter in the house of Sieglinde and her husband, Hunding. Sieglinde comforts him and invites him to share their meal. Hunding, however, recognizes Siegmund as his enemy, but the laws of hospitality dictate that guests remain unharmed under his roof. Later, after Sieglinde has drugged Hunding into a deep sleep, she comes to Siegmund and they sing of their love and desire ["Love Music of Siegmund and Sieglinde"]. She tells how she was carried away by Hunding during a raid and forced to become his bride, and how her father, Wotan, had promised her she would be rescued one day by a hero who could free a sword (called Nothung—“Need”) that the god had thrust into a tree when he unexpectedly appeared at her wedding. Memories are stirred, and the connections between the lover-twins are revealed to them in their full significance. With one powerful motion, Siegmund frees the sword and displays it to the enraptured Sieglinde. They embrace fervently and rush into the night ["The Lovers Flee"]. Hunding, intent on fighting Siegmund, pursues them. Wotan and Brünnhilde, his favorite among his nine warrior-daughters known as Valkyries, watches him gaining on them. Brünnhilde tells her father that she will protect Siegmund from Hunding, but he orders her not to interfere. She tries to disobey him, but he allows Siegmund to be slain and Nothung, his sword, to be shattered. Wotan then strikes Hunding dead. After gathering together the shards of Nothung, Brünnhilde flees with Sieglinde, pregnant by Siegmund with Siegfried. Wotan angrily runs after them ["Wotan’s Rage"]. The Valkyries, having taken fallen heroes to Valhalla on their flying horses, gather on a rocky mountaintop ["The Ride of the Valkyries"]. Brünnhilde gives Sieglinde the pieces of the shattered sword and sends her to a nearby forest where she can safely deliver Siegfried. Wotan enters and punishes Brünnhilde for her disobedience by making her mortal and putting her to sleep on the mountaintop. He bids his beloved daughter a poignant farewell and surrounds her with a magic fire that can only be penetrated by a hero worthy of her love ["Wotan’s Farewell and Magic Fire Music"].

Siegfried (1856–57, 1869–71), the third of the Ring operas, is devoted to the young hero, raised since the death of his mother by the smithy dwarf Mime. As Siegfried begins, the treasure is in the possession of the giant Fafner, who, by using the magical golden helmet, has changed himself into a dragon to guard it. Mime, coveting Fafner’s hoard for himself, tries repeatedly to forge a sword for Siegfried strong enough to slay the fearsome monster, but the mighty youth smashes each one ["Mime’s Fright"], so Siegfried creates a weapon for himself from the shards of Nothung, the sword of his father ["Siegfried Forges the Magic Sword"]. Mime and the swaggering youth appear before Fafner’s cave. Blasts from Siegfried’s horn awaken the dragon, who emerges to confront the intruders. Siegfried plunges his sword into the monster’s heart ["Siegfried Slays the Dragon"; "The Dragon’s Lament and Death"]. Drops of the dragon’s blood burn his hand, and when he licks off the blood he can miraculously understand the song of the Forest Bird ["Forest Murmurs"]. The Bird tells Siegfried that the treasure is now his but that he should be wary of Mime, who intends to poison him to gain the gold for himself. Siegfried can now understand the true intent behind Mime’s honeyed words and slays the dwarf. The Forest Bird has yet another message for Siegfried—the Valkyrie Brünnhilde sleeps on a rock surrounded by fire, to be awakened only by the kiss of one who knows no fear. “That is I,” shouts the ardent Siegfried, who follows the Forest Bird to find the woman for whom he is filled with longing. Siegfried beholds Brünnhilde for the first time and awakens her with a kiss that ignites their rapturous love.

In Götterdämmerung (“Twilight of the Gods,” 1869–74), dawn breaks after the preceding nighttime scene during which the three Norns (the Fates of northern mythology) foretell the inevitable cataclysm and the downfall of the gods. Morning finds Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerging from the cave in which they spent their bridal night ["Daybreak at Brünnhilde’s Rock"]. Reluctantly, Brünnhilde urges her lover to set out on further deeds of valor. They exchange pledges of undying love and precious gifts—Brünnhilde receives the fated Ring made from the gold of the Rhine; Siegfried gets the noble steed Grane. With ecstatic protestations of love, Siegfried departs ["Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey"]. Meanwhile, Hagen, who, like his father, the dwarf Alberich, also lusts after the Ring, gathers his cohort to wrest it from Siegfried ["Hagen’s Call to His Clan"]. When Siegfried appears, Hagen gives him a potion that makes him forget his love for Brünnhilde. Siegfried journeys back to their cave ["Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens"] and takes the accursed Ring from the stricken Valkyrie. Brünnhilde follows Siegfried back to the Hagen’s abode. Hagen arranges a hunting expedition during which he slays Siegfried and commands his vassals to bear the body back to his hall ["Siegfried’s Death and Funeral March"]. In the closing scene of the Ring cycle, Brünnhilde receives the slain body of Siegfried with the realization that he was the instrument through which the gods worked to release the world from the curse of the Ring. She orders a huge funeral pyre erected and her noble steed, Grane, brought forth. In a sweeping monologue ["Brünnhilde’s Immolation"], she vindicates Siegfried’s valor and actions, then draws the Ring from the hero’s finger as he is lifted onto the pyre. Grabbing a torch, she ignites the platform and hurls the firebrand at Valhalla. She mounts Grane and vaults into the flames to die with her beloved. The Rhine surges over its banks, allowing the Rhine Maidens to reclaim the Ring, thereby ending its awful curse. The purging waters recede, and Valhalla, home of the gods, can be seen burning in the distance as the final curtain descends.