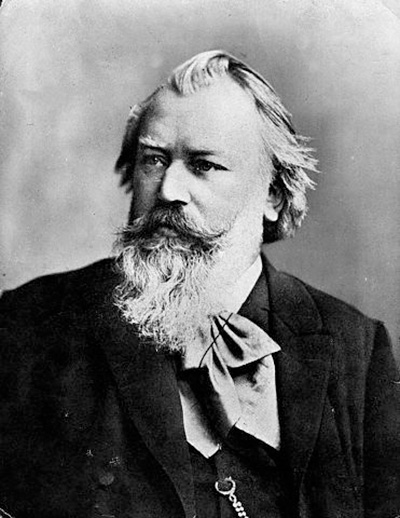

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Concerto No. 1 in D Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 15

- Composed: 1854-59

- Premiere: January 22, 1859, Hannover, Germany with Brahms as pianist.

- Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: January 1925, Fritz Reiner conducting; Wilhelm Bachaus, piano. Most Recent: December 2018, Louis Langrée conducting; Yefim Bronfman, piano.

- Duration: approx. 44 minutes

Brahms began writing what became his first Piano Concerto when he was only 21. At the time, he had not completed any multi-movement works for orchestra, and, not surprisingly, he was confronted by numerous technical challenges. He was also wrestling with intense personal problems, many of which were associated with the demise of his dear friend and mentor, Robert Schumann. In 1854, not long after meeting Brahms, Schumann attempted suicide, and, as a result of his psychological and physical condition, he was sent to a psychiatric hospital at Endenich. Brahms and a few of his friends rushed to support Robert’s wife, Clara (a famous concert pianist), and their children, and he remained at their home overseeing the running of the household when Clara resumed her concert tours. He had such a central role in the life of the family that he was named as the godfather of the Schumanns’ youngest child, Felix, who was born after Robert was institutionalized. Brahms was also the conduit for Robert and Clara’s messages because the doctors initially barred Clara from seeing her husband, who they feared would become too excited. Schumann passed away in July 1856, by which time Clara’s and Brahms’ lives had become intertwined and, while this brought them great comfort and joy, it also produced anxieties.

Brahms’ D Minor Piano Concerto came together in stages. In 1854, he sketched a three-movement sonata for two pianos, but before completing it he realized that his vision was for a work on a much grander scale. So he revised and redesigned his material for a symphony in the key of D minor; the same key as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. While overwhelmed by concerns that this symphony would be compared to Beethoven’s masterpieces, and still learning to write large forms and how to handle the orchestra, Brahms dreamt he was playing a concerto based on his “hapless” symphony. Once again he shifted gears, this time expanding and incorporating his ideas into a piano concerto, specifically the Op. 15, D Minor Piano Concerto. The first movement of the concerto drew on material from his earliest efforts on the aborted two-piano sonata, but the second and third movements were conceived specifically for the concerto. He completed the second movement in 1857 and the third in 1856.

Throughout his career, but especially in his early years, Brahms often turned to colleagues for advice, in some cases asking them to critique his work on new compositions, including sketches of pieces that were still incomplete. While writing the concerto, he called on Clara Schumann for advice, and he sent multiple drafts to Joseph Joachim. Joachim, who at the time was Brahms’ closest friend, was one of the 19th century’s most outstanding violinists and a composer in his own right, and Brahms greatly benefitted from his extensive experience playing with numerous high caliber orchestras. Clara and Joachim had heard excerpts of the rejected sonata and symphony and were delighted with the way Brahms transformed and expanded them for the new concerto. But Joachim did not serve merely as a tutor; he and Brahms had a genuine partnership, inspiring and assisting each other. While Brahms was writing this concerto, Joachim was working on his own violin concerto, which was also in D minor. Both men were influenced by Beethoven, and they aimed to create concertos that had the same type of structural integrity and gravitas as those of the older master, rather than ones that conformed to the type of popular, modern concertos that were merely virtuoso showpieces. Nevertheless, despite the guidance and support of his friends, Brahms was plagued with insecurities, writing to Clara on one occasion of his “frustration.”

The first performance of Brahms’ Piano Concerto, in March 1858, was a type of informal private hearing. Joachim led this performance with his orchestra at Hannover (Germany) and Brahms played the solo piano part. Throughout his life Brahms used these types of trial performances to check the effectiveness of his new works, and particularly their orchestration. After he spent another year making various adjustments and alterations, the same performers gave the work an official premiere in 1859 and then, a few days later, it was performed at the Leipzig Gewandhaus with the Leipzig orchestra and Brahms playing the piano solo. But Leipzig had yet to be won over by Brahms’ music. After the performance, Brahms wrote to Joachim that neither the audience nor performers welcomed the work, and there was very little applause after the performance, although there was some hissing. Brahms put on a brave face, claiming that he had played better than he had done in Hannover and that he was not deterred by what he acknowledged as a “brilliant and decisive—failure.” But he also claimed that he would improve the work so that it would be better received. “I believe this is the best thing that could happen to one; it forces one to concentrate one’s thoughts and increases one’s courage.” Nevertheless, the negative reaction in Leipzig did have an impact; companies were reluctant to publish the work and the full score was not published until 1874. By this time, the concerto had had numerous well-received performances, and the Leipzig one no longer mattered.

The first of the three movements, with its formidably difficult piano part, resembles the intensity of a Herculean tragedy. In contrast, the inner movement is more intimate, beginning with mournful bassoons. It is often regarded as a tribute to Robert Schumann, but Brahms wrote to Clara that it was a “gentle portrait” of her, and the dialogue between the piano and orchestra suggests the intimacy of the two. Upon hearing the movement, Clara remarked that it had “something churchly about it; it could be an Eleison.” Indeed, at the same time that he was struggling to write the concerto Brahms was studying the sacred music of Palestrina. On his autograph manuscript, Brahms inscribed the opening melody of this movement with words from the Latin Mass, “Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.” Scholars have varying interpretations of these words, some believe it refers to the composer’s study of Palestrina, while others note that Joachim and Brahms referred to Robert Schumann as “Mynheer Domini” (“honored master”). To be sure, these interpretations may co-exist. The rollicking third movement has often been compared to the finale of Joachim’s Hungarian Concerto, the same one he was working on when Brahms wrote his piano concerto, and both movements are influenced by the mood and structure of the finale of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. Brahms’ rollicking movement creates a vibrant conclusion for his work.

—Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts