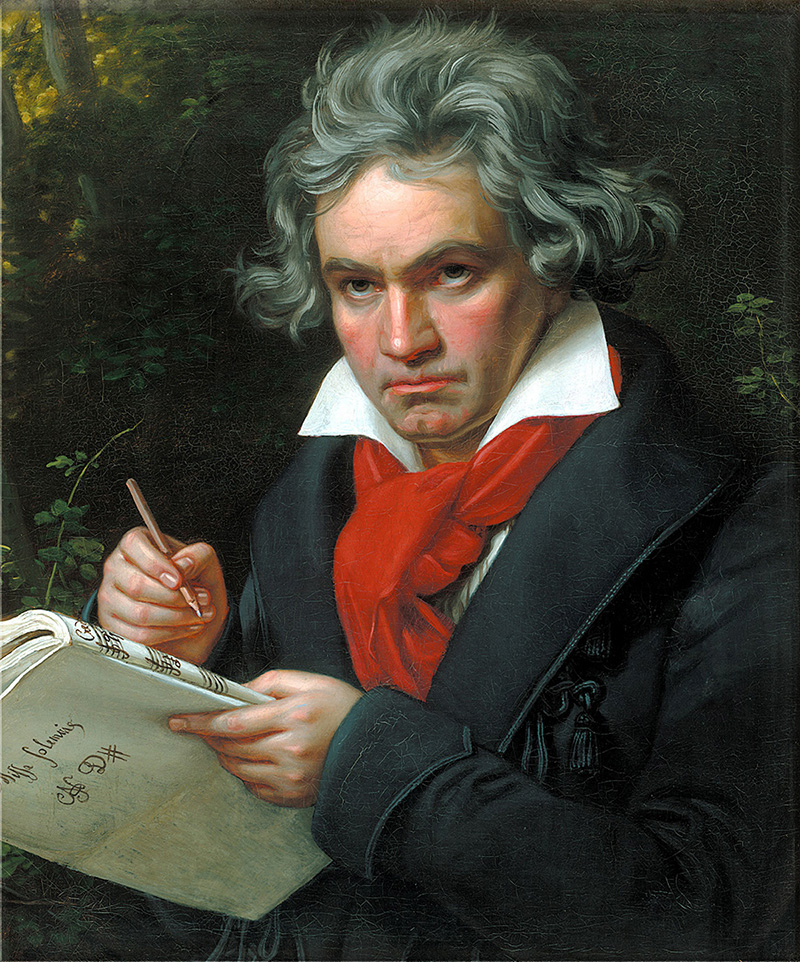

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Serenade in D Major for Flute, Violin and Viola, Op. 25

- Composed: Published in Vienna, 1802

- Premiere: Unknown

- Duration: approx. 24 minutes

Although Ludwig van Beethoven did not submit his Serenade Op. 25 for publication until the year 1801, the stylistic features of the composition suggest an origin much earlier in Beethoven’s career. In 1802, his Viennese publisher, Giovanni Cappi, released them under the opus number 25, but the composer soon peddled another arrangement of the work—one that he claimed was the work of another musician—to a second publisher in Leipzig. Ludwig van Beethoven’s reputation for Geschäftssinn, his shrewd “business sense,” was certainly well earned.

As a young man in Vienna seeking to establish himself, Beethoven invested a great deal of effort into the most marketable genres of music. Piano concertos were the most advantageous, since they placed him in front of an audience in three simultaneous roles: conductor, soloist and composer. But in addition to churning out the usual trios, quartets and sonatas for violin and cello, he experimented with other combinations of instruments as well, often as a means to flatter dilettantes and colleagues. Between 1792 and 1801, he completed 13 compositions for ensembles of unusual configurations and sold them to multiple publishers whenever possible.

The Serenade Op. 25 follows the structure popularized by the light-hearted divertimenti of Haydn’s generation. Quick-tempo outer movements bookend a suite of inner movements typically including a pair of minuets, an adagio and a set of variations, although Beethoven turns one of his minuets into a scherzo.

The Entrata (“Entry”) is a processional march beginning with imitation horn calls before evolving into call-and-response figures between the flute and strings. The following minuet has two trios, one a dialogue between violin and viola, the other for solo flute over an Italianate lute accompaniment in the strings.

The Allegro molto in 3/8 time is fiery and unsettling. The composer juxtaposes minor against major, volatile against predictable. The following theme and variations showcase the composer’s ingenuity in compensating for the lack of a bass instrument. The theme appears in double stops, followed by variations in which each of the players has their moment to show off.

The brief scherzo movement features a cheerful motive in dotted rhythms, offset by a legato middle section. The final Adagio barely lasts 24 measures before launching into a rondo with gallant dotted rhythms, in which the composer surprises the listener with lopsided rhythms and unpredictable chromaticisms before concluding with a tongue-in-cheek coda.

—Dr. Scot Buzza