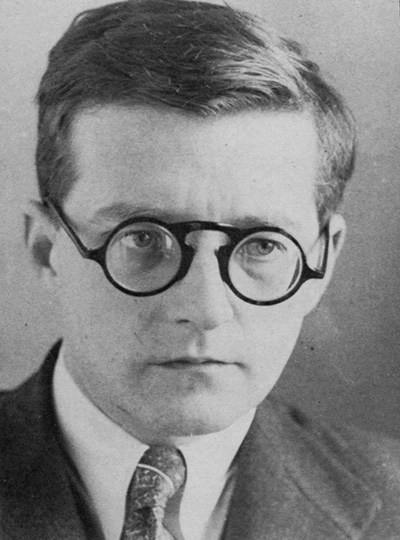

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Died: August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia

Symphony No. 11 in G Minor, Op. 103, The Year 1905

- Composed: 1957

- Premiere: October 30, 1957 by the USSR Symphony Orchestra, Natan Rakhlin conducting

- Instrumentation: 3 flutes (incl. piccolo), 3 oboes (incl. English horn), 3 clarinets (incl. bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, chimes, crash cymbals, snare drum, tam-tam, triangle, xylophone, harp, celeste, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: February 2007, Yakov Kreizberg conducting. Most Recent: May 2015, Louis Langrée conducting.

- Duration: approx. 55 minutes

Shostakovich, who was 11 years old at the time of the October Revolution, spent his entire adult life under the Soviet regime and never knew another political reality first-hand. There is plenty of evidence that he was deeply ambivalent about Communism, but he was just as deeply marked by its ideology, for which no alternatives were available to him. Thus, he was neither able nor willing to avoid political themes, although he treated them in ways that could be open to interpretation. His Symphony No. 11 has been seen both as an homage to officialdom and as a work with a hidden dissident message.

Ostensibly, the work commemorates the first Russian revolution of 1905. This uprising grew out of a peaceful demonstration of workers and peasants in front of the Winter Palace, the Czar’s residence in St. Petersburg. They wished to hand Nicholas II a petition, asking the monarch to alleviate their economic conditions, which had become unbearable. The Czar’s guards began to shoot at the crowd, killing hundreds of people. The event, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” set off widespread strikes and protests all over the country. The massive unrest led to a certain liberalization in Czarist rule, bringing the empire closer to a constitutional monarchy for the last decade of its existence.

The events of 1905 were widely regarded by Soviet historians as a prelude to the two revolutions of 1917 (February and October), the first of which put an end to the Czarist regime and the second brought the Bolsheviks to power. For this reason, writing a symphony about the 1905 revolution may seem to have been a politically expedient thing to do. But the truth is that the brutality of Bloody Sunday would have aroused the deepest revulsion in every sensitive person, and the program of the symphony expresses a deep belief in human dignity in general. Some writers have alleged that, while Shostakovich was ostensibly concerned with the events of 1905, what he was really thinking about was the Hungarian revolution of 1956, crushed by Soviet tanks shortly before the symphony was written. The composer himself was heard to comment on the fact that he wrote the Eleventh in the aftermath of the Budapest uprising. Yet the symphony ultimately transcends any concrete event to denounce all tyrants and mourn for victims of injustice everywhere.

In this symphony, Shostakovich took special pains to ensure his message was clear to every listener. He adapted many of the symphony’s principal themes from songs of the workers’ movement—songs that every resident of the Soviet Union learned to sing in school—as well as from his own work for mixed chorus, Ten Songs of Nineteenth-Century Revolutionary Poets, Op. 88 (1951). He then wove these themes together in a complex tapestry, having them undergo substantial transformations and bringing them back repeatedly, sometimes in their original form and sometimes with important changes, in the course of the symphony’s four movements (which are played without pause).

With these characteristic building blocks, Shostakovich created what resembles a veritable opera without words. It portrays not just emotions and musical characters but definite places and actions. (It is no coincidence that the symphony was later choreographed with great success in Russia.) The eerie opening, where a slow-moving melody is played in five simultaneous octaves by the muted strings, is a striking depiction of the motionless Palace Square on an ice-cold January day. This frozen image returns several times as a powerful contrast to the intense drama unfolding in the second movement. The contrast between motion and immobility is one of Shostakovich’s main dramatic strategies in this work: the delirious activity in the second and fourth movements is offset by the calm, yet extremely tense, music in the first and third.

The slow first movement (“The Palace Square”) sets the stage for the drama, with the glacial string theme, a trumpet call that turns into a wail, a hint at the Orthodox response “Lord have mercy on us,” and two prison songs. It clearly represents “silence before a storm,” and the storm does break out in the second movement (“The Ninth of January”). Against an agitated accompaniment in the lower strings, we hear a melody usually described as “Mussorgskyan,” first softly and then gradually rising in volume until a full orchestral fortissimo is reached. All of this is, however, only a prelude to what follows. After a brief recall of the “frozen” opening of “The Palace Square,” the most violent section of the symphony begins: a ferocious fugue, started by cellos and basses, and rapidly escalating into a graphic depiction of sheer horror—the entire orchestra pounding on a single rhythm of equal triplet notes, at top volume and (for most instruments) in a high register. This is certainly the moment where the Czarist guards open fire. The first-movement image of the empty Palace Square then returns.

The Russian title of the third movement, “Vechnaia pamiat” (“Eternal Memory”), alludes to a funeral chant of the Orthodox church, but it is actually based on the “Worker’s Funeral March,” a well-known revolutionary song, played by the violas to the sparest of accompaniments. A second, less subdued section develops and leads to an impassioned passage where the entire orchestra erupts, apparently suggesting a flashback of the past atrocities. The mood then becomes calmer for a while, but the fourth movement, “Tocsin,” sounds the alarm bells with a new call to battle. The relentless march rhythms grow more and more violent until, finally, they are swept aside by another climactic moment when a theme representing the plea to the Czar is played with great fervor by the full orchestra. The glacial string music of the first movement returns, complemented by a long English horn solo, before the final upsurge with musical material taken from the second movement, suggesting that the struggle is far from over.

It is hardly the optimistic conclusion that one would associate with a piece celebrating Soviet political ideas. Then again, according to Soviet history books, the 1905 revolution had been unsuccessful because it failed to overthrow the Czar. That historic moment was not to arrive until 1917, and it was perhaps inevitable that Shostakovich should devote his next symphony, No. 12 (1961), to the Great Socialist October Revolution, as it used to be called. The finale of that work, “The Dawn of Humanity,” delivered the triumphant ending everyone had been waiting for.

In the Eleventh Symphony, Shostakovich rendered unto Caesar the things which were Caesar’s: a large-scale symphony on an official theme, using plenty of songs officially sanctioned by the regime. (It was enough to make some people comment at the premiere: Shostakovich had “sold himself down the river.”) But there were enough disturbing overtones in the work for others to perceive another, hidden layer of meaning. According to one report, Shostakovich’s son, Maxim, 19 at the time of the premiere, whispered into his father’s ear during the dress rehearsal: “Papa, what if they hang you for this?” And the great Russian poet, Anna Akhmatova, said, when asked what she thought of all those revolutionary songs quoted in the symphony: “[They] were like white birds flying against a terrible black sky.” Clearly, Shostakovich had created neither a Communist propaganda piece nor a coded anti-Communist tract but a complex, dark score of exceptional dramatic power.

—Peter Laki