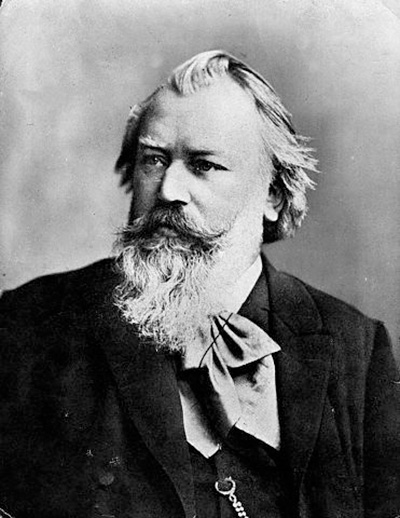

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Ein Deutsches Requiem (“A German Requiem”), Op. 45

- Composed: 1865-68

- Premiere: December 1, 1867, Vienna (mvts. 1–3); April 10, 1868, Bremen (mvts. 1–4, 6–7); February 18, 1869, Leipzig (complete)

- Instrumentation: solo soprano and baritone, SATB chorus, 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, 2 harps, organ, strings

- CSO notable performances: First CSO: April 1955, Thor Johnson conducting; Eleanor Ryan, soprano; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone (his U.S. debut); Miami University Chorus; CCM Chorus; Mt. St. Joseph Choir; Tri-State Masonic Choir. Most Recent CSO: November 2008, Paavo Järvi conducting; Heidi Grant Murphy, soprano; Matthias Goerne, baritone; May Festival Chorus, Robert Porco, director. First CSO at May Festival: May 1906, Frank Van der Stucken conducting (a concert in memory of Theodore Thomas); Johanna Gadski, soprano; David Ffrangcon-Davies, baritone; May Festival Chorus; Adolph H. Stadermann, organ. Most Recent CSO at May Festival: May 2012, James Conlon conducting; Nicole Cabell, soprano; John Relyea, bass-baritone; May Festival Chorus, Robert Porco, director. Other: October 1972, soprano Kathleen Battle with baritone Ronald Corrado, Thomas Schippers conducting.

- Duration: approx. 70 minutes

From its initial performances in Austria and Germany, Brahms’ A German Requiem was acclaimed not only as his most significant composition to date, but also one of the most important choral works of the 19th century. Regardless of its status, this is one of the composer’s most personal works, being partly inspired by the death in 1856 of Robert Schumann, his beloved mentor. Brahms wrote most of the work during 1865–1866, although he drew on a few ideas he had sketched during 1854, at which time the strength of his friendship with the Schumann family was deepening. While he finished six of the seven movements during 1866, he wrote the fifth in 1868. This movement, featuring a lyrical soprano solo, is closely associated with his mother, who died in 1865 while he was working on the composition.

Prior to completing the Requiem, Brahms’ career had seesawed. While he was first introduced to the public with much fanfare, he also faced fierce criticisms. In 1856, before Brahms had published any compositions, Robert Schumann proclaimed him the “Messiah” of the next generation of composers and prophesized that he would create pathbreaking, wonderful large-scale works for orchestra and chorus. With Schumann’s backing, Brahms began publishing his early compositions, which were mainly songs and piano solos. He was a highly accomplished pianist, but he had little experience with the orchestra. To address this deficiency, he consulted more experienced friends, including the great violinist Joseph Joachim, and gradually mastered the art of orchestration and compositional techniques that would enable him to create larger-scale compositions. He attained recognition for chamber compositions for combinations of strings and piano, but his first large scale work, a Piano Concerto in D Minor, Op. 15, was met with mixed reviews. The Requiem, however, enshrined his reputation as one of the most significant composers of the era, with critics indicating that Robert Schumann’s prophecy had been realized. Indeed, when Clara Schumann was writing in her diary about Brahms conducting one of the first performances of this work, in 1868, she was reminded of her husband’s prophecy: “As I saw Johannes standing there, baton in hand, I could not help thinking of my dear Robert’s prophecy, ‘Let him but once grasp the magic wand and work with orchestra and chorus,’ which is fulfilled today. The baton was really a magic wand and its spell was upon all present.”

Unlike the Requiems of Mozart, Berlioz and Verdi, Brahms’ does not employ the words of the traditional Latin Requiem Mass of the Catholic church. Rather, he selected passages in German from the Protestant Bible. He assembled the text of the work himself, using 16 verses from the German Protestant Bible. He did not follow the Bible’s ordering of these verses, and, in a few movements, he combined verses from two or more different books. Expressing resignation, consolation and hope, the words he chose offer comfort to those who grieve. But, unlike the Latin Requiem, there is no reference to Jesus, which surprised a few critics of the time. The German words and the musical style, which is heavily influenced by German composers such as Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, marked the work as distinctively German. Its ties to German nationalism were further solidified by performances honoring German soldiers returning from the Franco-Prussian War. But Brahms’ contemporaries, in Europe and the United States, also believed it transcended national borders because it reflected the types of emotions that those coping with a bereavement experience.

At first, American choirs sang the Requiem in English translation, but they had trouble with Brahms’ difficult vocal lines, and, as a result, the American premiere did not occur until 1877, when it was performed in New York. In contrast to the choir at this performance, a choir in Ohio, which had more than 300 singers, rehearsed for two years before giving the Cincinnati premiere in 1884. Despite uneven performances, critics in Europe and the United States praised Brahms’ deeply expressive music—even ones who expressed doubts about the music’s affect—and acknowledged the composer’s ingenious compositional technique.

Each of the seven movements features deeply moving passages. The slow opening movement— “Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted”— is initiated by the violas, rather than the higher, brighter violins. The lower instrument contributes to creating a mysterious sound, as if a veil is gradually lifted. The gentleness of this movement contrasts with the march-like dirge of the second. Drawing on larger orchestral forces, it begins with images of death—“For all flesh is as grass”— but builds to a triumphant passage, in a fast brighter section that promises eternal joy—“pain and suffering shall flee away”— before closing softly. The third movement —“Lord, teach me that there must be an end of me”— begins with a prayer-like section for baritone solo and ends with a lengthy choral fugue accompanied by a notoriously long sustained pitch in the brass, lower strings and timpani. Numerous critics, including James Huneker, a flamboyant and influential American writer of the end of the 19th century, interpreted the amazing length of this pitch as God’s enduring strength. Others recalled that the first performance of the movement, in Vienna, was ruined when the timpanist played this pitch so loudly the voices and other instruments could not be clearly heard. The tensions of this movement are relieved by the gentler fourth movement, “How amiable are Thy tabernacles, O Lord of hosts!,” which has fewer passages of complex counterpoint than the third. Critics have frequently praised the opening of this movement for its exquisite lyricism and hymn-like texture. Its emphasis on high pitches contrasts with the low colors of the preceding movements. But the fifth movement— “You now have sorrow, but I will see you again”— has earned even more plaudits, and it was frequently performed as a stand-alone piece during the 19th century. Its concluding reference to the comfort provided by a mother are perhaps related to Brahms’ memories of his own mother. The grand sixth movement, although beginning softly, is one of the most dramatic movements of the work. The words “at the last trumpet” are thrillingly intoned to brass accompaniment, and they are followed by an exciting climax that leads to a closing fugue. A 1904 critic in The New York Sun described this movement as “literally Titanic.” Contrasting with the excitement of the sixth movement, the Requiem ends with a short, poignantly flowing movement that quietly consoles— “Blessed are the dead, which die in the Lord.”

—Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts