CSO Concerts This Winter Offer Themes Ranging From Harmonic Exploration to Heroes’ Journeys

by Hannah Edgar

The selections you hear on CSO programs are, almost always, the fruits of a deft compromise. Artistic committees talk shop with conductors and soloists to figure out what’s in their repertoire, or what they’ll be playing on the road at the time of their engagement. The Orchestra then squares that with any artistic preferences on their side—a hankering for a contemporary work, perhaps, or a piece providing an overdue highlight to symphony musicians—and sorts out an evening-length program.

During all that scheduling Jenga, cohesion is usually an afterthought. Most programs turn out, by necessity, a bit random, with no discernible throughline.

Mark it as both coincidence and blessing that no fewer than four CSO programs this winter turned out highly thematic. Some themes are immediately apparent, like Sir Donald Runnicles’ and Dame Jane Glover’s explorations of a single composer: Johannes Brahms for Runnicles (Jan. 5–7), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart for Glover (Jan. 27 & 28). Others are more evocative: conductor Kevin John Edusei’s program (Jan. 19 & 20), for example, explores the inventive ways composers utilize harmony.

Glover, a renowned Mozart scholar, is often asked to lead portrait programs of the composer. One memorable survey in Philadelphia started with Mozart’s first symphony, which he wrote when he was eight, and ended with his last, the Jupiter.

Her bookends in Cincinnati are a little closer together. Glover’s program ends with the Symphony No. 36, Linz, one of Mozart’s mature symphonies; before that, she’ll dust off a rarely heard bit of juvenilia with the Symphony No. 13, which Mozart wrote when he was just 15. Between the two symphonies is the much-beloved Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364 for solo violin and viola, spotlighting CSO principals Stefani Matsuo and Christian Colberg.

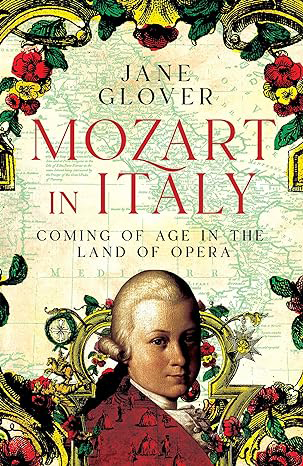

Glover specifically requested to lead the Symphony No. 13. Her latest book, Mozart in Italy: Coming of Age in the Land of Opera, traces Mozart’s teenage travels in Italy with his father, Leopold. It was a hugely influential period for the young composer: he produced this early symphony in 1771, during the second of three such trips. At the time, father and son were prolonging their stay in Milan, where Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa had commissioned the young Mozart for an opera, Ascanio in Alba. Leopold had hoped the opera’s success would move the Empress to grant him or his son a royal appointment. It wasn’t to be, but Mozart tossed off the Symphony No. 13 in the meantime.

In his Pegasus Pocket Guide to Mozart, musicologist Sir Nicholas Kenyon asserted that Mozart’s 13th is his last symphony in a “conventional mode.” Glover agrees. Her book points to this symphony—as well as Mozart’s K. 111a and K. 113, written around the same time—as an example of Mozart trading contrapuntal writing for the highly lyrical, operatic style then in vogue in Italy. That experience, her book argues, changed Mozart’s compositional voice for good.

“After that, he started making his own rules…. He just followed his unbelievable instincts,” Glover says.

The Sinfonia Concertante, penned when the composer was 23, is a hallmark. Mozart’s writing unusually emphasizes the viola’s sonority, not just through the solo part but in the ensemble: the viola section is split into two parts, like a violin section would usually be, and the orchestra’s dynamic range hovers around mezzo for most of the piece.

Mozart, like many great composers, had a special affinity for the viola, often opting to play it in a chamber setting. His own experience on the instrument almost certainly influenced what is, more than the split viola section, the Sinfonia Concertante’s most unique compositional quirk: Mozart asks the viola soloist to sharpen the instrument’s strings by a half-step, or scordatura tuning. The violas of Mozart’s day, with their construction and milder gut strings, would have faced significant challenges projecting over the orchestra. The scordatura tuning makes the instrument more resonant. (In a fascinating interview with The Strad podcast [Episode 31], German violist Nils Mönkemeyer raises the possibility that Mozart may also have had a uniquely mild instrument, even by 18th-century standards. Mönkemeyer would know: he’s played Mozart’s viola.)

Today’s meatier, steel-stringed instruments can handily surmount those challenges. These days, the Sinfonia Concertante’s tuning question is now more of a choose-your-own adventure rather than a hard-and-fast rule. Glover, who conducts both modern and historically informed orchestras, mostly sees it played as Mozart intended. But Colberg hasn’t played it that way to date, despite having performed the Sinfonia Concertante since he was a youngster on both viola and violin. At this point, it would take longer to unlearn his non-scordatura fingerings—though he’s open to trying, knowing that Mozart’s preference also sits better in the soloist’s left hand.

“If I do it the way he wanted it, it makes it much easier. There are a lot more open strings, the finger patterns make a lot more sense, and overall, it helps the intonation, quite frankly,” Colberg says.

“Basically, Christian’s just enjoying making his life more difficult,” Matsuo teases.

While Colberg has been around the block with this piece, Matsuo hasn’t performed it yet. Her experience with the Sinfonia Concertante has so far come behind closed doors, complementing her viola-playing friends as they prepare the piece for performance. (“I feel like I know more violists who have played this than violinists, but I don’t even know how that’s possible when it always requires a violist and a violinist,” she says.) It’s also Matsuo and Colberg’s first time playing together in a concerto setting with orchestra, though they occasionally play together in chamber settings.

“The fact that the piece often echoes between the two instruments just highlights their differences in a wonderful way,” Matsuo says.

Those differences aren’t just sonic—they’re technical, too. Colberg says simplistic comparisons between violin and viola are a personal “pet peeve” of his.

“I know that we share a lot of the same techniques with violinists, but truly we are, at the very least, 80 to 90 percent a piccolo cello. Whenever I’m in doubt as to how to play something, I always look at the cellos, and how much weight and speed they’re using in the bow. I hardly ever look at the violins,” Colberg says.

“I was gonna say, there’s nothing more humbling than a violinist picking up a viola, hitting yourself in the face because it’s bigger than a violin, and being like, ‘Holy cow, how do I make this sound good?’” Matsuo says. “It’s a completely different concept of how to draw a sound. Violin is a lot more forgiving: you can over-press [with the bow], but with a viola, if you press it, it doesn’t work.”

Needless to say, Matsuo isn’t following Colberg’s instrument-swapping career trajectory anytime soon. Or is she?

She smirks at Colberg. “What if we just switched for the concert?”

■ ■ ■

EXT. — A POLITICAL RALLY IN A CROWDED CITY CENTER

Midday. The clouds above darken with the tumult of a coming storm. A platform is set up in a plaza. Atop it is a podium and lectern emblazoned with The Party symbol; a banner is set up behind. All around are Party dignitaries in solid-colored, militaristic garb.

A lone woman makes her way to the podium. She is a well-respected luminary of some kind, invited here on behalf of The Party—perhaps a writer, artist or intellectual. She makes her way to the podium and begins speaking. Her voice is low, calm, soft like velvet. The crowd quiets and leans in to listen.

But as she goes on, her voice becomes more agitated. She speaks passionately about corruption, abuses of power, human rights violations—all of which are rife within The Party. The uniformed faces behind her purple, like the sky. This is not The Party line.

VARIED VOICES FROM THE CROWD

(bleating and sharp, amid scattered boos)

Liar!

Shame!

Get her!

After an ugly struggle, in a sickening monochromatic surge, she is yanked from the podium by The Party men swarming around her. But those close enough to the podium can still hear her voice, soft as ever, repeating the truth to anyone in earshot as she is dragged away.

-END-

If the Lutosławski Cello Concerto was a movie, in Kian Soltani’s imagining, it might unfold something like this. Soltani, 31, talks about the classic cello concertos like they’re great films waiting to be shot—he’s admitted in other interviews that, if he weren’t a cellist, he’d work in the movie biz. (His most recent album, Cello Unlimited, includes arrangements from Pirates of the Caribbean, Lord of the Rings and Bourne Identity, to name just a few titles.) The Elgar concerto, for example, is about learning to accept one’s destiny. Meanwhile, Soltani hears the Dvořák as not just a hero’s journey but a progression through the stages of grief, with the protagonist learning to live without a lost love.

“Each of them has a narrative for me. I like to think more in those terms,” Soltani says.

Soltani has lived with the Lutosławski Cello Concerto, a celebrated but sorely underperformed piece, much longer than most cellists his age: he got his first big break playing the concerto in a winning performance at the Paulo Cello Competition, when he was just 21. Lutosławski wrote the cello concerto in 1970, during a period of peak disenchantment with Soviet leadership in Poland. Nonetheless, the composer maintained that his concerto did not have political overtones. The concerto’s dedicatee, Mstislav Rostropovich, disagreed, viewing it as a musical metaphor of living under—and resisting—fascism. These CSO concerts (Feb. 2 & 3) emphasize Rostropovich’s interpretation by pairing the concerto with Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11, a work which brought the composer back into good graces with the Soviet authorities.

Soltani, too, lands more on Rostropovich’s side of things. He sees the cello protagonist as “an individualist…an independent thinker” squared against a hostile mass that wants to muzzle him.

“That’s literally what happens at the beginning of the piece: Trumpets, which are so much louder than a cello can ever be, interrupt and silence you. And as you’re in the middle of the cadenza, you’re silenced by the orchestra and the conductor,” Soltani says. “[The cello] attempts to initiate dialogue, inviting people to play together—like, ‘Hey, there must be a way that we can meet somewhere, right?’ But after short episodes, it’s always back to being silenced: ‘No, we’re not interested in that.’”

That persists until the last movement, which Soltani hears as an “all-out war.” Then, “it’s time to fight”—but the victor remains unclear. We only hear the soloist shriek out high As at the end of the piece, reminiscent of the stoic, solitary Ds that open the piece. “It’s a cry of either victory or of pain,” Soltani says.

The ambiguity of this bleak ending—and its implication that there are, in the end, no real winners—feels fitting, and, unfortunately, ever timely. “You can apply it to any political situation these days: the wish for dialogue, the failure of such dialogue, and the suffering and violence that inevitably follow that,” Soltani says.

Sergei Rachmaninoff, whose Piano Concerto No. 2 will have been played by George Li just a few weeks before in Edusei’s program, was a contemporary of both Lutosławski and Shostakovich, but his music may seem to come from another planet—lush, tuneful, unspooling never-ending melodies.

Even so, Rachmaninoff absolutely shares his peers’ harmonic sophistication and attention to structure. Edusei finds the opening of that concerto especially radical in context—especially considering the flak Rachmaninoff got, and still faces, as a 19th-century nostalgist stuck in a flintier 20th century.

“The piece opens with just the chord structure,” he says—an F minor chord with a chromatic voice creeping within it. “For Rachmaninoff, who was definitely one of the greatest melodic writers, to start a piece totally vertically says a lot about where his compositional priorities were, or at least about his compositional process.”

Edusei didn’t plan for it but, coincidentally enough, both Samy Moussa’s Elysium, the 2021 piece which begins the concert, and John Adams’ Harmonielehre, a modern classic since it was premiered in 1985, both begin with straightforward choral statements: a silky B major chord in Elysium, pounding E minor chords in Harmonielehre.

They build exponentially from there. Elysium’s chord tones slide into new sonorities by way of juicy glissandos. Adams dresses up the repetition and rigorous rhythmic schemes of mid-20th century minimalism in big-boned, rich harmonies befitting Mahler, Sibelius and—yes—Rachmaninoff.

“It’s a program about harmony, and what harmony means in our time,” Edusei says.

But just as harmony can be a symbol for the challenges facing our world, it can also be a portal to another realm entirely. Edusei has loved Harmonielehre since, as a teenager, he stumbled upon Edo de Waart and the San Francisco Symphony’s world premiere recording in a thrift shop. He was totally thunderstruck.

“I had never before heard such a style,” Edusei says. “It’s a difficult thing to call it ‘minimalism,’ because it’s absolutely not minimalistic in the techniques that he uses. [Adams] more or less uses rhythmic patterns as a Morse code that connects different chords and materials. It has a completely different function, I find.”

Elysium is newer to Edusei—he began conducting it last year and has since led the UK and Belgian premieres of the work. But it’s no less affecting to Edusei now than Harmonielehre was to him as a young man. He confesses that Elysium’s climax, when a D major chord suddenly bursts from the texture, sends tingles up and down his spine every time he conducts it.

“I can say that about only a couple of pieces in the repertoire. That says a lot about this particular piece,” Edusei says.