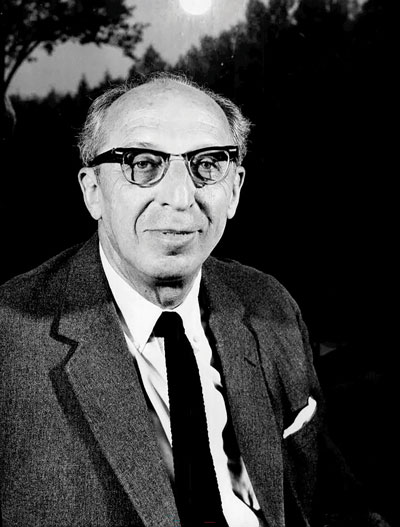

Aaron Copland

Born: November 14, 1900, New York City

Died: December 2, 1990, North Tarrytown, New York

Suite from Appalachian Spring

- Composed: 1943–44

- Premiere: Original ballet version for chamber orchestra: October 30, 1944, Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium, Louis Horst conducting. Orchestral suite version for full orchestra: October 4, 1945, Artur Rodziński conducting the New York Philharmonic.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, bass drum, glockenspiel, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tabor, triangle, wood block, xylophone, harp, piano, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: October 26, 1945 (shortly after the full orchestra version’s premiere in New York), conducted by Eugene Goossens. Most Recent: February 2016, Louis Langrée conducting. Notable: 1995 European Tour, Jesús López Cobos conducting. Recording: 1997 Aaron Copland: The Music of America, Erich Kunzel conducting.

- Duration: approx. 24 minutes

Since its creation at the twilight of World War II in 1943–44, composer Aaron Copland and choreographer Martha Graham’s Appalachian Spring has taken a place in America’s cultural pantheon, its music typifying the sound of the nation for many. But the project did not begin on such a trajectory. Indeed, Graham first approached Copland in fall 1942 with a scenario roughly based on the ancient Medea story. Copland refused the scenario (Samuel Barber later took it up with Graham) and instead suggested something Shaker-inspired. After some time and trials, Graham devised a script called “House of Victory,” inspired in part by the patriotic texts of Copland’s Lincoln Portrait (1942), about a young couple’s new pastoral life. Further revisions yielded an aspirational, peaceful frontier setting during the Civil War era, free of the Wild West action in other contemporaneous tales of American pioneering. Contrary to the singularity of Copland’s earlier Billy the Kid, Graham muted specificity, calling her characters the Bride, the Husbandman, a Pioneer Woman, a Revivalist Preacher (and his four female Followers), persons identifiable enough to generate drama but general enough for audiences to see themselves on stage. Mid-process, Copland imagined an even more abstract Americanism, thinking not of “Appalachian Spring,” but simply “A Ballet for Martha,” the score’s permanent subtitle. The choreography, score and a stage set designed by Japanese-born Isamu Noguchi convey a pluralism that dresses traditionalism in modernist guises. Graham infused her signature modern dance style with classical ballet’s formalism. Copland wrote 20th-century melodies and rhythms, couched in an approachable palate—neither too acerbic, nor sounding like Haydn. And Noguchi’s set was angular and sparse, pragmatically simple for mobility’s sake, but figurative enough for audiences to see a farmhouse, porch and rocking chair. As musicologist Annegret Fauser has written, this between-ness mirrors circumstances of the ballet’s creation at the end of World War II amidst a pivot toward American post-War peaceful leadership and exceptionalism.

The ballet premiered for the 80th birthday of heiress and philanthropist Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge in the auditorium at the Library of Congress that bears her name. Copland’s ensemble was suitably modest, including only 13 players. In 1954, he arranged the full score for large orchestra, but not before creating the famous suite for orchestra in 1945. For the suite, Copland noted that he cut connective and choreography-centric music, but he also eliminated the Revivalist Preacher’s vividly manic solo. Otherwise, the most drastic revisions modify the famous Shaker hymn variations on “Simple Gifts,” with a variation cut, another added, and others revised and reordered for musical coherence in the dance’s absence. The resulting suite retains Graham’s episodic, kaleidoscopic ballet structure while amplifying the optimistic change of atmosphere at War’s end.

The “Simple Gifts” variations constitute the focal point of the score, and, in the ballet, they appear during an extended duet between the Bride and the Husbandman. The hymn adds to the piece’s challenge to geography. The Shakers have typically dwelt in New England, upstate New York and across into Kentucky. The work’s title (which Graham added later, quoting Hart Crane’s poem “The Bridge”) and Southern-modeled Revivalist Preacher invoke separate locales, and a program note Graham wrote places the scene in Pennsylvania. That the most iconic portion of the score derives from vocal hymnody lends a palpable connection to communal singing, despite the score being entirely instrumental. The editor of the sourcebook where Copland found it noted that the song was “sung everywhere,” suggesting a beneficial ambiguity that brings out the music’s widely held connotations of universality. The hymn text’s images of freedom and being “in the place just right” further reinforce this subtext.

The suite has become Appalachian Spring’s most popular and frequently-performed version, and detached from a plot or stage set has proven especially capable of drawing audiences into its everyman spirit—film composers invoke Americana from its model, and it has been used by politicians of all stripes. For many listeners since Appalachian Spring’s creation, Appalachia in the music is not simply a narrowly defined region but a symbol for a wider American ethos.

—Jacques Dupuis