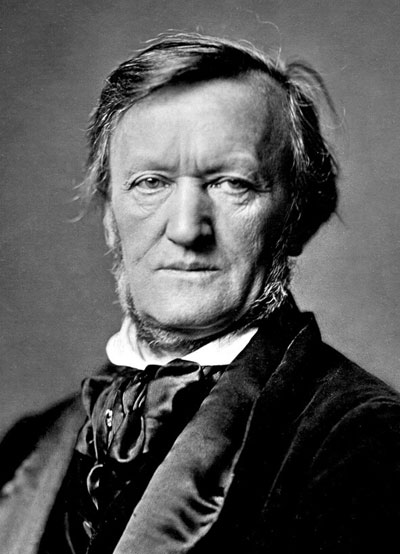

Richard Wagner

Born: May 22, 1813, Leipzig, Germany

Died: February 13, 1883, Venice, Italy

Overture to Tannhäuser

- Composed: 1843-1845

- Premiere: October 19, 1845 in Dresden, conducted by the composer

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, crash cymbals, suspended cymbals, tambourine, triangle, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: April 1895, Henry Schradieck conducting. Most Recent: September 2007, Paavo Järvi conducting. Notable: June 1996 as part of the Olympic Torch Ceremony at Sawyer Point. Recording: 1994, Wagner for Orchestra, Jesús López Cobos conducting.

- Duration: approx. 15 minutes

Although Richard Wagner is universally known as a composer, he also considered himself—as the author of the librettos for all of his operas, a huge autobiography and an avalanche of theoretical and philosophical tracts voluminous enough to literally fill a shelf—a poet and a man of letters. The sources of inspiration for his librettos were almost always the history and myths of Germany. The same was true when he was in search of an operatic subject while on vacation in the early summer of 1842 at the northern Bohemian town of Teplitz: he devoured a wide variety of 19th-century retellings of the ancient tales of the legendary Medieval singing contests. The accounts, by E.T.A. Hoffmann, the Brothers Grimm, Heine, Ludwig Tieck and others, concerned a historical 13th-century Minnesinger (i.e., a German poet-musician of noble birth) named Heinrich von Ofterdingen, a contest of song held in 1208 at the Wartburg Castle (near Eisenach, today remembered as Johann Sebastian Bach’s birthplace), and a (perhaps) mythical character called Tannhäuser who succumbed to the seductions of Venus in her mountain enclave and sought forgiveness through a pilgrimage to Rome and the love of a pure woman. Before he left Teplitz, Wagner had sketched an operatic scenario from these sources and, the following spring, worked it into a full libretto originally titled The Mountain of Venus, but later renamed Tannhäuser to thwart lascivious comment. The three acts of the opera were composed in 1844, while he was conductor of the Royal Opera House in Dresden; the orchestration was completed on April 15, 1845. Wagner directed the work’s premiere in Dresden on October 19, 1845 to an audience initially bemused by his attempts to weld together the individual numbers of the opera through accompanied narratives and instrumental transitions. By the third performance, however, Tannhäuser proved to be a success. It was repeated in Dresden in 1846 and 1847, with some revisions to clarify its dramatic structure, and was introduced into the repertories of the major European opera houses over the next decade. Tannhäuser was the first of Wagner’s operas to be staged in America (Stadt Theatre, New York, April 4, 1859; the Overture was played here as early as 1853, in Boston).

The opera opens in a grotto in the Venusberg, a mountain where Venus, the goddess of love, is said by German legend to have taken refuge after the fall of ancient civilization. Tannhäuser has forsaken the world to enjoy her sensual pleasures, but after a year he longs to return home and find forgiveness. He invokes the name of the Virgin Mary, and the Venusberg is swallowed by darkness. Tannhäuser finds himself in a valley below Wartburg Castle, where he is passed by a band of pilgrims journeying to Rome. His friend Wolfram recognizes him, tells him how Elisabeth, his betrothed, has grieved during his absence, and invites him to the Wartburg to see her and to take part in a singing contest. Elisabeth is joyous at Tannhäuser’s return, and they reassure each other of their love. At the contest, however, Tannhäuser sings a rhapsody to Venus and the pleasures of carnal love, which so enrages the assembled knights and ladies that Elisabeth must protect him from their threats of violence. Tannhäuser agrees to join the pilgrims to atone for his sins. Several months later, he returns from Rome, alone, haggard and in rags. He tells Wolfram that the Pope has said it is as impossible for someone who has dwelled in the Venusberg to be forgiven as for the Papal staff to sprout leaves. He considers going again to Venus, but withstands that temptation when Wolfram mentions Elisabeth’s name. Elisabeth, however, not knowing of Tannhäuser’s return and despairing of ever seeing her lover again, has died of grief. Her bier is carried past Tannhäuser, who kneels next to it and also dies. As morning dawns, pilgrims from Rome arrive bearing the Pope’s staff, which has miraculously grown leaves.

The Overture to Tannhäuser encapsulates in musical terms the dramatic conflict between the sacred love of Elisabeth and the profane love of Venus. For a series of orchestral concerts of his music in Zurich in 1853, Wagner wrote a grandiloquent synopsis of the Overture’s emotional progression, which reads in part: “At first the orchestra introduces us to the ‘Pilgrims’ Chorus’ alone. It approaches, swells to a mighty outpouring, and finally passes into the distance. As night falls, magic visions show themselves. A rosy mist swirls upward, and the blurred motions of a fearsomely voluptuous dance are revealed.... This is the seductive magic of the Venusberg. Lured by the tempting vision, Tannhäuser draws near. It is Venus herself who appears to him.... His heart and senses glow, the blood in his veins takes fire, an irresistible attraction draws him nearer, and he steps before the goddess. In drunken joy the Bacchantes rush upon him and draw him into their wild dance.... The storm subsides. Only a soft, sensuous moan lingers in the air over the spot where the unholy ecstasy held sway. Yet already the morning dawns: from the far distance the pilgrim’s chorus is heard again. As it draws ever nearer and day repulses night, those lingering moans are transfigured into a murmur of joy so that at last, when the sun rises in splendor and the pilgrims’ chorus proclaims salvation to all the world, the joyous murmur swells to the mightiest, noblest rejoicing. Redeemed from the curse of ungodly shame, the Venusberg itself joins its exultant voice to the godly chant.”

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda