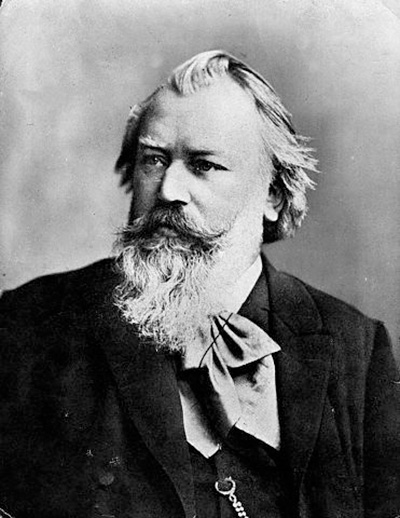

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Trio for Piano, Clarinet and Cello in A Minor, Op. 114

- Composed: 1891

- Premiere: December 12, 1891 in Berlin with Richard Mühlfeld playing clarinet, Robert Hausmann playing cello and Brahms at the piano

- Duration: approx. 23 minutes

By the year 1890, Johannes Brahms had declared his String Quintet in G Major, Op. 111 his swan song and announced his retirement from composing. The previous several years had not been easy ones, and he confessed to a confidante that he felt he had achieved enough: “Here I had before me a carefree old age and could enjoy it in peace.” However, when he met the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, he found himself captivated by the artist’s expressive control of the instrument. Thus, in the summer of 1891 he composed his Trio in A Minor, Op. 114, and the Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115. Two other pieces for Mühlfeld eventually followed: the Clarinet Sonatas in E-flat Major and F Minor, Op. 120.

Mühlfeld was employed in the court orchestra of Meiningen and had already established himself as an artist of the first rank. As Clara Schumann later remarked, “The man played so wonderfully, he might have been specially created for your works. I marveled at his profound simplicity and the subtlety of his understanding.”

Brahms had previously shown his fondness for the clarinet in his orchestral works, in particular the expressive possibilities of its three registers: the round, clear upper range, the soulful middle and the dark chocolate bottom end. However, even though the Trio Op. 114 was to be something of a showpiece for Mühlfeld, Brahms did not neglect the other two instruments; the cello takes center stage as often as the clarinet, and all three instruments are perfectly integrated throughout the work. Brahms’ friend, Eusebius Mandyczewski, marveled at the way in which the composer took full advantage of the lyrical qualities of the instrument. He wrote to the composer: “The inventive conception of the themes, born of the spirit of the wind instrument and, more especially, the harmonious blending of the tones of the clarinet and the cello, are magnificent; it is as though the instruments were in love with each other.”

The opening movement introduces a plaintive cello tune, to which the clarinet responds with an arching line. The piano breaks the mood with accented triplets, and these two subjects combine into a sequence of scales that pushes the movement to its first climactic point. The following arioso duet hints at exoticism before coming to rest once again in A minor. Brahms launches the development section with a chain of sixteenth-note scales that sweep the listener through several remote keys before once again settling in the home key. The brief coda churns up just the smoldering sparks of the previous themes before bringing the movement to a close.

The Adagio begins with a delicate aria that the clarinet soon hands off to the cello, while singing a countermelody in the octave above. The placid mood soon gives way to a deeply stirring second theme in which each instrument takes its turn accompanying the others before the movement returns once again to the tranquility of the opening.

The third movement is quintessential Brahms: an Andantino grazioso waltz of infectious charm that is only slightly perturbed by the trio section, itself the quiet memory of a Bavarian Ländler. The composer abbreviates the return of the opening waltz before coming to rest with several quiet chords in the piano.

The final movement recalls the musical language of a younger Brahms from decades previous: turbulence, harmonic tension and rhythmic displacement are among its most salient characteristics, as are fleeting hints of the fire and alla zingarese spirit that had been hallmarks of earlier works such as the Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 25. In this movement there is no chance of a peaceful ending. Instead, he weaves several canons together throughout the piano, cello and clarinet lines until the music gathers momentum and crashes to a decisive close.

—Dr. Scot Buzza