The American Mosaic

PART 1: JMR’s Vision of America

by Tyler M. Secor

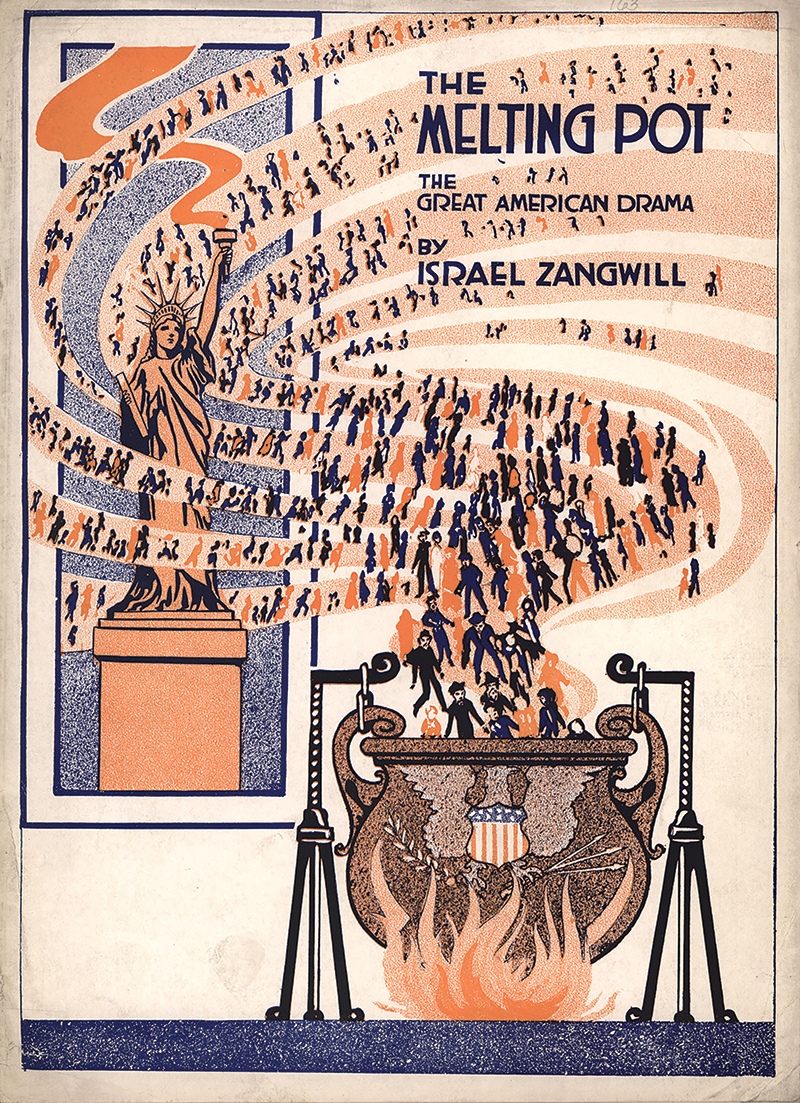

“The Great American Melting Pot” is a common metaphor for the American experience. The term “melting pot” was popularized in the United States by the 1904 play The Melting Pot, written by Israel Zangwill about a Russian Jewish family who fled the 1903 Kishinev Massacre for America, where their hope for all ethnicity to “melt away” could be realized. David, the hero and main character, declares:

There she lies, the great Melting Pot—listen! Can’t you hear the roaring and the bubbling?... What is the glory of Rome and Jerusalem where all nations and races come to worship and look back, compared with the glory of America, where all races and nations come to labour and look forward!

But this melting pot theory doesn’t quite capture John Morris Russell’s view of America. “I don’t see America as a big gray slurry,” JMR firmly states. “We are not one homogeneous population that all dines on the same fast food and jives to the same music.” Instead, JMR believes the American experience is better described as a mosaic.

“Everyone in America brings their own special piece to our great panorama,” explains JMR. “The cultural heritage, experiences and perspectives that people bring with them from around the world are like the pieces of a giant mosaic—each distinctive in color, shape, texture, and each beautiful in and of itself. And yet, when all those individual pieces are put together they create an enormous picture of incredible depth and vibrancy that is so much more than the mere collection of those individual parts. As a mosaic, the American experience becomes so much more multidimensional and nuanced, and expresses the enormous opportunity and promise of a diverse society.”

JMR’s fervor over the idea of the American Mosaic is palpable, infectious and almost evangelistic—not some esoteric ideal but, rather, an idea put into action.

“We love Cincinnati specifically because of the diverse communities that have created and continue to create a legacy of cultural vitality here,” says JMR, a perspective he is bringing together on the Music Hall stage for the April 12–14 concerts, The Dream of America. “This program is a love letter to those who have brought the world to the Great Midwest,” reflects JMR. “It tells the story of the immigrant experience through Ellis Island over a century ago and resonates in the amazing cultural mosaic we enjoy in Cincinnati today.”

JMR and the Cincinnati Pops will be joined onstage by the vibrant artistic communities that call Cincinnati home:

This isn’t the first time the Greater Cincinnati Indian Community Choir and Shanti Choir, founded in 1994 by Dr. Kanniks Kannikeswaran has joined the Orchestra. The choir, whose repertoire is based on Classical Indian Ragas, was part of the 2014 Classical Roots program and the 2019 Look Around experience.

Cincinnati Baila! Dance Academy’s mission is to bring the proud Hispanic heritage of dance, music and traditional culture to children across Greater Cincinnati. Through dance, Cincinnati Baila! gives children the skills that will serve them for life and keeps the Hispanic tradition alive.

Cincinnati’s Donauschwaben Schuhplattlers, or shoe clappers, keeps the highly energetic Bavarian folk dance tradition active in Cincinnati. The Schuhplattlers are no strangers to working with the Pops, who have brought their jumping, slapping and spinning dances to the Pops since 1995.

Ijo-Ugo Performing Arts Company, Cincinnati’s theatrical African dance and drumming company, seeks to bring awareness to African dance in the diaspora. Ijo-Ugo makes its Pops debut in The Dream of America.

McGing Irish Dancers first joined the Pops in 1997 and teaches the rich history of Irish dance to children and adults. McGing was the first school in North America to have a female, male and team world champion, which ranks them as one of the most prestigious dancing programs in the world.

With this concert, the Alliance of Chinese Culture & Arts USA makes its Pops debut. Its mission is to share Chinese culture, develop “East meets West” programs and partner with professional arts organizations to host public events. It is also committed to bringing Asian culture and arts communities together to showcase Asian creative expression with the hopes of building a more vibrant and prosperous community through the power of arts.

“This is what the Pops is all about: bringing people together with great music.… This is going to be fun!”

■ ■ ■

PART 2: The Dream of America

by Scot Buzza

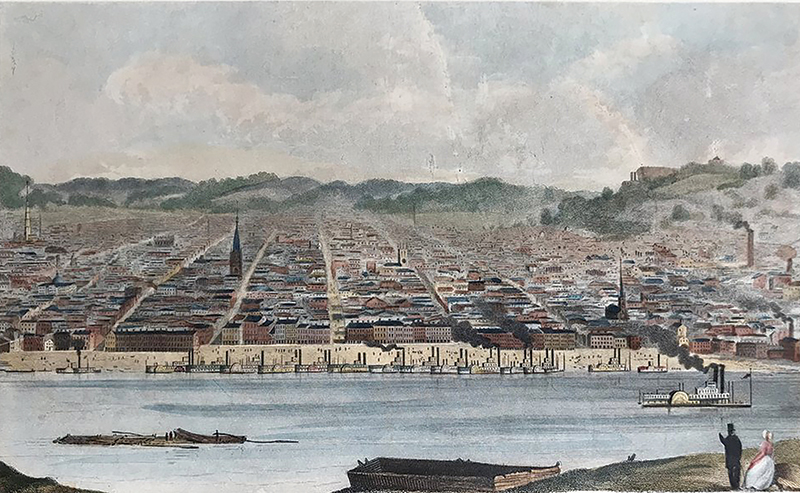

Cincinnati in the 19th Century. The face of Cincinnati began to change in the first half of the 19th century as waves of immigrants arrived with their families. Coming from Germany in the 1830s, from Ireland in the 1840s, and from European Jewish communities several decades later, they fled starvation, persecution, disease and political instability. Because of their differing religions, languages, cultures and skin colors they were often disparaged; yet, their contribution to the economic stability of the city was undeniable. Among them were highly skilled artisans, bakers, brewers, carpenters, day laborers, farmers, firemen, machinists and masons. The assets they brought were considerable: loyalty, family devotion, optimism, faith, resilience and an iron work ethic. And yet, by the second and third generations, most immigrant families had become so well assimilated that they forgot the struggles of their parents and grandparents. Sometimes they became intolerant and xenophobic themselves.

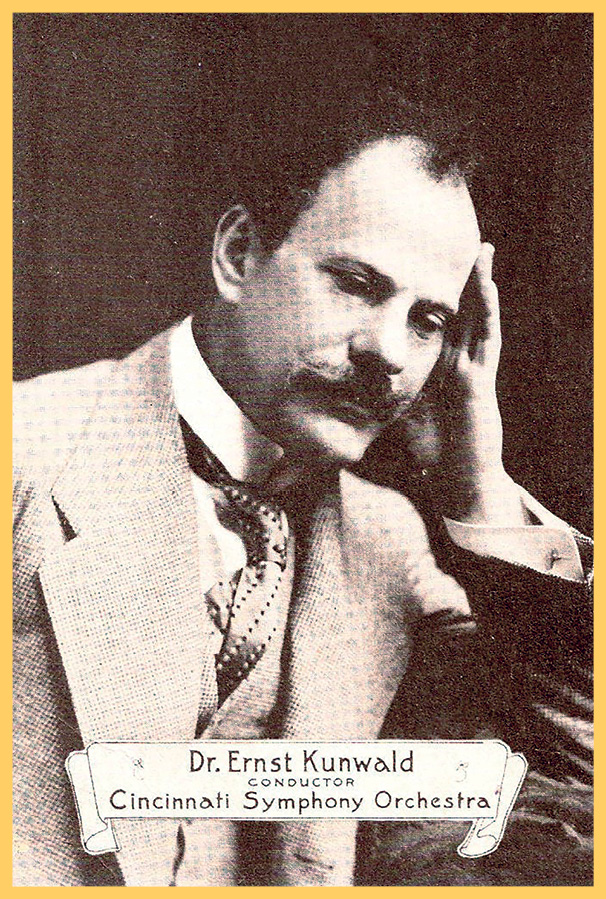

By the early 20th century, opposition to the immigrant presence had taken on a more sinister tone. Signs such as “No Irish need apply” and “Speak English” were hung for public view with no trace of shame. The American declaration of war on Germany in 1917 provoked an even more pernicious wave of anti-immigrant sentiment, particularly against Cincinnatians of German descent. As the city scrambled to whitewash its immigrant roots, Bremen Street became Republic Street, the German Mutual Insurance Company was rebranded as Hamilton County Insurance, and Over-the-Rhine was renamed Columbia. A particularly shameful event was the arrest of the music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Austrian-born Ernst Kunwald, who was imprisoned based on concocted allegations at the Fort Oglethorpe internment camp for the duration of the war and then ultimately deported with no charges filed (Read more about the Dr. Kunwald story in "Anti-German Sentiment + Ernst Kunwald").

A Record of Living Memory. In 1999, when American composer Peter Boyer was brainstorming ideas for a large-scale concert work for actors and orchestra as a commission for the opening of a new theater at the Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts in Hartford, Connecticut, he began to explore the richness of immigrant histories. He knew he had found the subject matter for his piece when he visited the Oral History Project maintained by the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, which preserves interviews with real-life immigrants about their experiences immigrating to the United States by way of Ellis Island. Boyer says, “I started going through this treasure trove of material. There are nearly 2,000 interviews, so it’s vast. And I realized: this is what the piece will be.”

Boyer culled 120 of those interviews from the archival collection and, from those, transcribed verbatim the first-person narratives of seven immigrants that he wove into a rich orchestral fabric. He sorted through hundreds of historical photographs to provide a visual backdrop for the musical score, giving the narrative an authenticity of time and place. The result was a 45-minute multimedia work, Ellis Island: The Dream of America, that both mirrors and amplifies the emotional dynamics of each individual story—at times funny, heartrending, disturbing and uplifting.

Boyer explains, “When the orchestra is accompanying these stories [actors relay the seven immigrants’ first-person narratives], it is very much like a documentary that is unfolding in front of you, and the orchestra is providing underscore. It does something that only music can do, which is amplifying the emotional content. So a big challenge of the piece was: how do I keep the orchestra restrained and not sonically overwhelm the voices?”

“The Voices that Built America.” The first of those voices is that of Helen Lansman Cohen, who describes her harrowing arrival into New York Harbor from Poland in 1920:

We couldn’t get off the boat because there were so many people on Ellis Island. So we had to stay on the boat six days. They ran out of food. We only had bread and water. When we finally got on Ellis Island my father sent a telegram to his brothers to come and get us.

Another of those stories comes from Helen Rosenthal, whose family was murdered at Auschwitz. She was 30 years old in 1940, the year she came to the U.S. by way of Ellis Island. She and her husband, Paul, lost everything and everyone dear to them, but she found strength in looking forward and rebuilding their lives:

If you hate, you lose yourself. There’s nothing left in this world after hate. I can’t hate. I have never been taught to hate. Even after pogroms, after all that happened in our town, my father tried to explain. I was 10 years old—

I asked that question, “why?” There was no answer to it. There still isn’t.

The Narrative Power of the Orchestra. In spite of the force of the stories, there is nothing sensationalistic nor perfunctory in Boyer’s underscoring for each of these monologues. Indeed, the extraordinary subtlety of the music is the key to its authenticity and its power to elicit empathy. First atmospheric, then melodic, it turns on a dime, constantly modulating in mood and key as the subtext of the narrative shifts.

“To balance that against what an orchestra can do naturally,” Boyer says, “which is part of why we love orchestras so much, is that it has this power, this narrative power, this emotional power on its own. So the way the piece ultimately got structured, then, was to create this prologue, which is just the orchestra alone, introduce the principal themes of the piece that the audience will hear in various guises, and then alternate between underscore for the stories and interludes that will allow the orchestra to speak up and be an orchestra.”

Although Ellis Island consists of 1,049 measures in 15 sections, it changes character so seamlessly that transitions go unnoticed.

Boyer says, “My goal was that the audience would perceive this completely organically, so that from the time we start to the time we end, 45 minutes and seven stories later, we have felt like there is one broad narrative that encompasses all of this.”

The progression of the work as the stories unfold leads to the introduction of a familiar symbol, represented in the words of Katherine Beychok, a Russian Jewish immigrant from Russia who arrived in New York Harbor in 1910:

The water was blue, the sky, it was a beautiful day. Everybody was laughing and crying that they were here; they’re in America.… And, of course, the first thing I had seen was that lady, the Statue of Liberty. It was a thing I can never forget to this very day, because when I think of her, when I think of the Statue of Liberty, I feel so wonderful and so good. I don’t think there’s anything under the sun that can make me feel better. It seemed that she was a vision from heaven, and it’s been with me ever since.

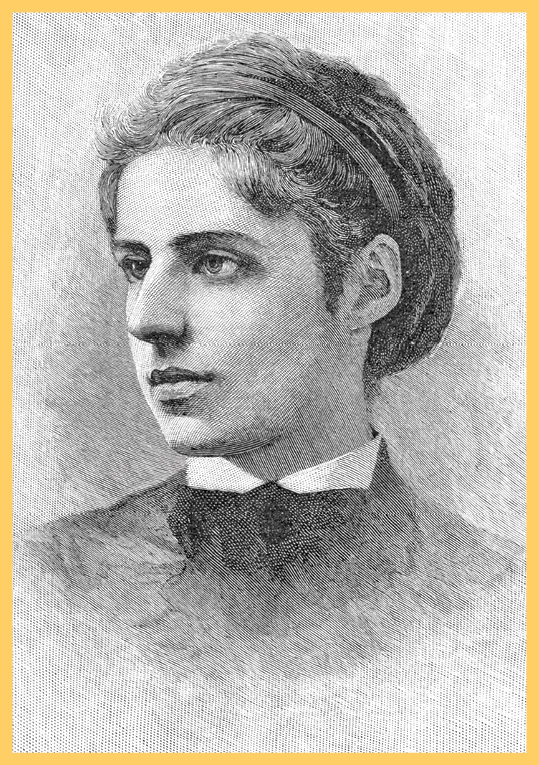

Beychok’s testimony provided Boyer with a natural way to launch into the high point of the piece: Emma Lazarus’ famous sonnet, “The New Colossus.”

“Beychok talked about how she felt looking for the Statue of Liberty when she was coming to America and then when she looked back on it, what that meant to her,” Boyer explains. “And it was these beautiful words, and then she speaks of the sonnet. When I found it, it was like, ‘Eureka! That’s it—that’s how I get into the sonnet.’”

The verse “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” is familiar to every American school kid and, Boyer points out, is regarded as not only iconic but nearly mythological. It is part of how we tell ourselves our own history, that history that belongs to each of us. “The audience has been introduced to the seven individuals and their seven individual stories, and when they all come back you have this immigrant chorus, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” explains Boyer. “That has great power because then they all participate in the sonnet.”

Yet, when the piece climaxes in the recitation of Lazurus’ poem by the ensemble of seven actors, it is no longer the power of the narrative, but rather, the power of Boyer’s musical language and the power of the full orchestra that finally provide emotional release to the tension that has built over the previous 40 minutes.

“Americanness” in Music. Giants such as Bernstein, Copland, Gershwin and, later, John Williams have often been credited with creating the enduring notion of “Americanness” in music. Boyer finds that he, too, has come to be associated with an American sound. “This piece is a big part of that reason I have come to be identified as an ‘American-sounding’ composer,” states Boyer. “It’s been much more of a natural, organic process. I’ve spent so much of my life studying those other composers’ output—really studying, from back in college days, all of the available scores that I could get my hands on. It has kind of seeped into my bloodstream as an American composer.”

That is not to say that Boyer has intentionally emulated other composers. It is natural, he points out, that early Beethoven sounded a lot more like Haydn because that was the musical language he had absorbed in the air around him as he developed his own voice. However, he concedes that the underscore to the Manny Steen story in Ellis Island is unique, in that Boyer made the conscious choice to evoke—not duplicate—the Tin Pan Alley idiom, tying it to the specific historical context of 1920s New York.

“The hard part is to try to honor a tradition without just pandering, without imitating it in an empty way. I’ve always tried very hard not to do that.” Boyer continues, “But when I sit down at this keyboard and play notes, all of those notes are always informed by all this music that is in my head, all the music that I’ve heard.”

Ellis Island in a Contemporary Context. Boyer notes that Ellis Island: The Dream of America is still in its original form. Unlike some composers, whose works go through continual revisions and edits, Boyer feels certain that he “got it right the first time. It sounds exactly as it sounded in April 2002.” What has indeed changed in the 22 years since its premiere is the ugly baggage that the word “immigrant” has taken on, echoing the strident political climate of 100 years ago.

“September 11, 2001 occurred while I was writing the piece. In terms of days on which the world pivots, I mean—Pearl Harbor, September 11—it was one of those days that felt like the whole foundation of the world is shaking and you wonder how are you gonna respond,” reflected Boyer. “And because this was a piece that was really about something fundamental to American identity, ultimately I decided it doesn’t make sense to change the piece. This terrible event has happened but I’m going to continue just the way I imagined that it should be. And then if it takes on a different kind of resonance, then so be it.”

Ellis Island: The Dream of America has since become one of the most frequently performed American orchestral works of recent decades. In 2005, Peter Boyer was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition for the work. Ellis Island has been performed more than 250 times by more than 120 orchestras and was filmed for broadcast in the PBS Great Performances series in 2017. In 2019, Boyer received the Ellis Island Medal of Honor for his work.