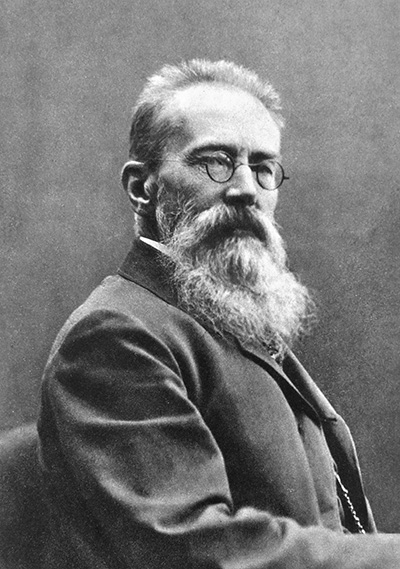

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

- Born: March 18, 1844, Tikhvin, Russia

- Died: June 21, 1908, Lyubensk, Russia

“Dance of the Tumblers” from The Snow Maiden

- Composed: 1880-81

- Premiere: (complete opera) February 10, 1882 in Saint Petersburg at the Mariinsky Theater

- Duration: approx. 4 minutes

Rimsky-Korsakov considered Snow Maiden to be the best of all his works—a statement that may come as a surprise, since the opera is largely forgotten today. The work’s length and its many vast, almost immobile tableaux pose considerable challenges to any contemporary stage director, yet the beauty and freshness of the music is undeniable. The four-movement suite the composer drew from the score offers no more than a few highlights from this opera in prologue and four acts (and nothing at all of the highly expressive vocal writing for the principal characters).

The Snow Maiden was an early example of a spoken play set to music (as opposed to an opera based on a libretto written expressly for a composer to use). The play in question was by the most important Russian dramatist before Chekhov: Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky, known to opera lovers today as the author of The Storm, on which Janáček based his Káťa Kabanová. Most of Ostrovsky’s works are realistic dramas like The Storm; The Snow Maiden, set in prehistoric, pagan Russia, is a fairy-tale-in-verse—a genre he only tried this once. (The play was first performed in 1873, with incidental music by Tchaikovsky.)

The Snow Maiden, daughter of Bonny Spring and Old Father Frost, longs to leave her forest home and live in a human community. That community, the Berendeys, welcomes her and her beauty soon attracts a wealthy suitor; the Snow Maiden, however, has a heart of ice and is incapable of love. Only toward the end of the opera—after a series of events too long to be recounted here—is she granted the ability to love but, being made of snow, she melts away when exposed to the rays of the sun. Her death placates Yarilo, the Russian sun god, who had been withholding his blessings from the Berendeys but now reappears to grace the land with his life-bringing warmth once again.

Rimsky-Korsakov incorporated many Russian folk melodies in the opera, both from his own collection and from other sources. Some of these were already alluded to in the play by Ostrovsky, who quoted their lyrics. In his autobiography My Musical Life, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote at length about the folk-music sources he used and also vented his indignation at the critics who failed to recognize that some of the melodies in folk style were in fact by him.

The "Dance of the Skomorokhi" (or "Dance of the Tumblers"; Skomorkhi can also be translated as "buffons") is a celebration of the spring within a forest. Tsar Berendey requests the "buffoons" to tumble and dance.