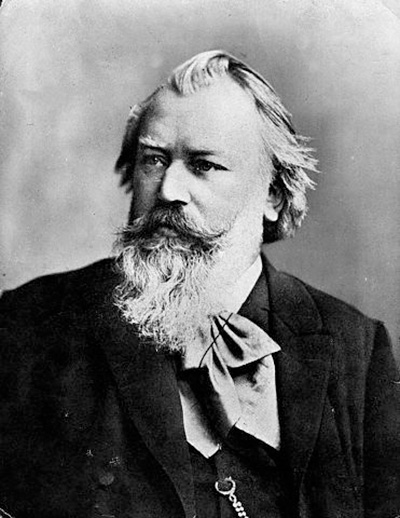

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73

- Composed: 1877

- Premiere: December 30, 1877, Vienna.

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: March 1896, Frank Van der Stucken conducting. Most Recent, Special Concert: October 2016, Louis Langrée conducting. Most Recent, CSO Subscription: March 2016, Louis Langrée conducting. Other: February 1995, Iván Fischer conducting; February 1943, Arturo Toscanini

- Duration: approx. 43 minutes

Although Brahms struggled to complete his First symphony, he seems to have had far fewer difficulties with the Second. He wrote it quickly between June and October in 1877, while he was still preparing the score of the First for publication. Similarly, the work’s bucolic mood contrasts with the drama and tension of the First Symphony. Brahms wrote most of the Second Symphony during his summer vacation at Pörtschach, in the southern region of Austria. The experience must have been enjoyable and gratifying because he returned to this location during the following two summers, writing the Violin Concerto, Op. 77, in 1878 and the Violin Sonata, Op. 78, in 1879. Perhaps in a whimsical mood, Brahms told Eduard Hanslick, a close friend and one of the most influential music critics in Vienna, that the air in Pörtschach was full of cheerful, lovely melodies. He knew that Hanslick preferred his lyrical works to his complex ones and teasingly suggested the critic would think he wrote the symphony “specially for you or even your young lady!” He told another of his friends, Theodor Billroth, “the melodies fly so thick here that you have to be careful not to step on one.” On hearing the work, Billroth described it in similarly sunny, pastoral terms: “It is all rippling streams, blue sky, sunshine, and cool green shadows.” In addition to picking up on Brahms’ description of the scenery and atmosphere of Pörtschach, he indicated that he knew Brahms had far fewer difficulties writing this work than some of his others: “A happy, blissful atmosphere pervades the whole, and it all bears the stamp of perfection and effortless discharge of lucid ideas and warm emotion.” Brahms completed the symphony while he was staying in Baden-Baden, near Clara Schumann’s home. She was immediately captivated when he played parts of the first and last movements to her on the piano. Composers are often surrounded by sycophantic admirers, but Billroth and Schumann were not in the habit of shying away from harshly critiquing Brahms’ ideas. That they only had praise for the Second Symphony is a clear indication of their genuine admiration for it.

Hans Richter with the Vienna Philharmonic premiered the Symphony in December 1877. The outpouring of enthusiasm for the work led to numerous other performances and, during the next two years, it was given throughout Germany and Austria, as well as further afield in Amsterdam, Moscow, New York, Boston and Milwaukee. Theodore Thomas conducted the American premiere in New York in 1878 and the first performance in Cincinnati in 1880, after previously leading performances of the First Symphony in both cities. Like many others, a Cincinnati critic preferred the Second Symphony to the First, praising its “kaleidoscopic variety” of orchestral colors and observing that its textures were more transparent (that is, less cluttered) than those of the First.

The first movement begins rather unusually, with a lyrical melody played by the cello. This melody provides the impetus for much of the movement, as well as for some of the melodies in the following three. But almost immediately there is a pause and the trombones and tuba quietly enter with longer notes, creating a momentary change in mood. Although brief and quiet, this passage causes enough of an interruption that one of the composer’s colleagues, Vincenz Lachner, protested. Brahms defended himself with a rather uncharacteristic acknowledgment indicating that this passage related to his bleaker moods: “I would have to confess that I am, by the by, a severely melancholic person, that black wings are constantly flapping above us.” Like dark clouds, similar short, sustained brass passages recur a few times throughout the movement, and their melancholic mood occasionally tinges the other movements as well. Brahms hinted that these phrases are related to the somber motet Warum ist das Licht gegeben dem Mühseligen? (“Why is the Light Given to Those Who are Sorrowful?” Op. 74, No. 1), which he completed after the Symphony, writing of the motet: “It casts the necessary shadow on the serene symphony and perhaps accounts for those timpani and trombones.” But compared to the choral work, the Symphony’s first movement as a whole is more relaxed, recalling the bucolic aura of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony and the prominence it gives to the wind instruments.

The subdued opening to the slow second movement, with its gently ponderous cello melody and plaintive bassoon accompaniment, create an introspective mood likely related to the brass phrases in the first movement. Brighter phrases from the flute and an ethereal, dance-like second theme lift the mood and lead to a few loud, tempestuous phrases. But they are swiftly quelled, and the movement returns to the melancholy atmosphere of the opening. Although it ends quietly, the somber kettle-drum rumblings under the last statement of the beautiful main melody seemingly portend future troubles.

Fritz Simrock, Brahms’ publisher and friend, predicted the third movement would be “irresistible for an audience” and observed that the “last seems to lift all its listeners back into heaven, which, moreover, we already found in the first movement.” Both the third and fourth movements are lighter than the first two, and in contrasting ways they recall Classical-era style, with the concluding Allegro con spirito being reminiscent of the high-spirited last movements of Haydn’s symphonies. An American music critic, who heard the work when it was performed for the first time in Milwaukee in December 1878, described the Classical elements in the third movement as creating a “perfect balance of unity and variety.” He seemed, however, to have been caught off guard by the movement’s structure, which he described as a “peculiarity.” The main sections, which are marked Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino), are twice interrupted by significantly faster, energetic sections (marked Presto ma non assia), which feature loud, somewhat heavy central phrases. These sections function like a trio in a minuet or scherzo. Beethoven had created similar alternations in some of his scherzos, but he usually did not employ the type of tempo contrasts that characterize Brahms’ movement. Like many a third movement of a Classical symphony, this one does not include the trumpets, trombones or tuba, and, as a result, the type of introspective phrases that are heard in the first movement are absent. The brass, however, return toward the end of the fast last movement. This time, they conquer the solemn doubts they had expressed in the first movement, and join the other instruments in an exhilarating conclusion.

—Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts