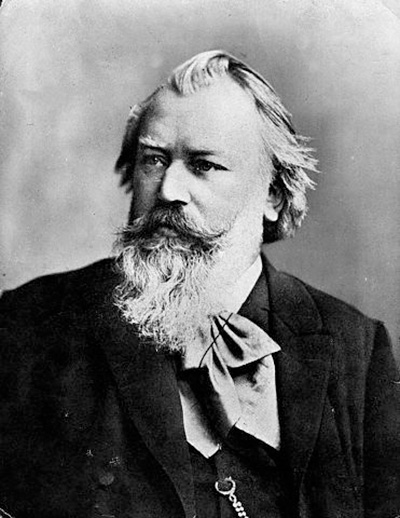

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died: April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria

Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 77

- Composed: 1878

- Premiere: January 1, 1879 in Leipzig, with the composer conducting and Joseph Joachim, violin

- Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: January 1900, Frank Van der Stucken conducting; Leonora Jackson, violin. Most Recent: May 2018, Louis Langrée conducting; James Ehnes, violin. Notable Violinists: Fritz Kreisler (1908, 1912, 1915, 1944), Jascha Heifetz (1930, 1934, 1938, 1947, 1956), Isaac Stern (1949, 1962, 1969), Midori (1989), Itzhak Perlman (1992), Jennifer Koh (1998), Joshua Bell (2002), Gil Shaham (2006, 2013), Christian Tetzlaff (2009).

- Duration: approx. 38 minutes

In retrospect, it seems inevitable that Johannes Brahms would compose and dedicate a violin concerto to his dear friend and colleague Joseph Joachim. Yet, the path to completing the concerto was perhaps not so predictable. Joachim was one of the most outstanding violinists of the 19th century, having first earned accolades from critics with performances of concertos under the baton of the famous composer Felix Mendelssohn. He met Brahms in 1853, when Brahms was working as a pianist for another violinist. Although the two men were around the same age, Joachim had far more experience as both a composer and performer. He had also established an impressive network of friends who numbered among the leading musicians in Europe. It was Joachim who introduced Brahms to Robert and Clara Schumann, and this new friendship contributed to the rapid establishment of Brahms’ reputation as a composer.

Brahms began writing his Violin Concerto in the summer of 1878. By this time, he was one of the most important composers in Europe. He had garnered considerable acclaim with his A German Requiem, and he had penned two symphonies, a piano concerto, numerous solo piano works and a variety of chamber music and lieder. Nevertheless, despite his experience writing for the violins in his orchestral and chamber works, he sought Joachim’s advice on numerous passages in the Violin Concerto; he also talked about writing idiomatically for the violin with other performers whose techniques were not as amazing as Joachim’s. In addition to their discussions, Brahms and Joachim tested early versions of the work, with Brahms at the piano playing what would be become the orchestral part. Although we cannot know exactly what they talked about, much of the history of the concerto, particularly details about the creation of its solo violin part, is documented by an unusually large number of detailed sources. These include letters between Brahms and Joachim and Brahms’ manuscript of the score, which is now owned by the Library of Congress. This manuscript is mainly in Brahms’ handwriting, but it also includes suggestions by Joachim, some of which were written in a color of ink that differed from Brahms’ notations. While historians have used this score to assist in reconstructing how the work was composed, modern performers, including the American violinist James Buswell, have gleaned new perspectives from it that have influenced how they play the concerto.

The solo violin part is known for its great technical difficulty. Brahms was very aware that it would challenge many players, and he asked Joachim to point out passages that were “difficult, awkward, impossible” to play. Joachim not only identified such phrases, he also wrote out alternate ones. Brahms incorporated some of these ideas into his work, but not all of them. It seems that he simply wanted to see options for specific passages and to reassure himself that his own ideas best suited the work. Joachim also insisted that the tempo of the finale should be marked as not too fast, otherwise it would be too difficult to perform, and he provided a few alternative passages for solo violinists with small hands.

Joachim pushed Brahms to finish the concerto in time to premiere it on January 1, 1879, with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. He played the violin solo while Brahms conducted. But neither man gave his best performance, the audience was not impressed, and both men realized that the work needed further revisions. In particular, Brahms reduced the sound of the orchestra so that it did not overwhelm the soloist. Joachim immediately scheduled other performances, and by April 1879 he had presented the work in London, Vienna, Budapest and Cologne, thus establishing it as “his” concerto.

In addition to assisting Brahms with various matters in the main sections of each movement, Joachim created the cadenza that is performed toward the end of the first movement. This showpiece, which is usually played in performances today, perfectly matches the virtuosity of the rest of the movement and complements the movement’s formal features, including its development of the main themes. It is, of course, calculated to display Joachim’s astounding playing technique. In the 20th century as well as in our own era, many violinists continue to play this cadenza, but even in Brahms’ own lifetime other performers created their own. Indeed, Brahms was said to admire the cadenza his friend Richard Barth (1850–1923) wrote. Barth performed it in 1880 and 1881 during concerts that Brahms conducted. More than 18 other performers, including legendary violinists of the 20th century such as Fritz Kreisler and Jasha Heifetz, also wrote their own cadenzas. In the first performances of the concerto in Boston and New York in 1889, the soloist Franz Kneisel (1865–1926) performed a cadenza he had created. In contrast, in a performance a few years later, Kneisel played a cadenza written for him by the American composer Charles Martin Loeffler (1861–1935). Maud Powell (1867–1920), an even more popular American violinist who had studied with Joachim, wrote her cadenza in 1891 and performed it with the Chicago Orchestra in 1908.

Although Brahms had thought of creating four movements for the concerto, he settled on the customary three. The first is characterized by numerous contrasting moods. For instance, the first section played by the orchestra opens with a soft, enchanting melody played by the horns and oboe, but it closes with bold march-like phrases. The violin then makes its first appearance, immediately establishing its dominance with furious crossing of the strings and fast, wide-ranging scales. One of the most beautiful, delicate moments occurs toward the end of the movement, after the cadenza, when the solo violin and oboe quietly recall the first theme. The oboe also plays the opening melody of the slow second movement, but here it is accompanied by the horn and the other winds. Whereas the solo violin enters with an energetic solo in the first movement, in the second it takes up the oboe’s melody and gently ornaments it in a lyrical, touching rhapsody. This combination of oboe and violin also provides a soft, tender conclusion to the movement. Despite the dazzling virtuosity of the outer movements, early commentators, including those who had heard the London premiere, drew attention to the beauty of this movement, suggesting it would be the most popular of the three. The lively finale greatly pleased the first audience in Leipzig. Its fiery, dance-like Hungarian style is another homage to Joachim, whose family was Hungarian. Joachim used the same style in the finale to his Second Violin Concerto (1857), which he both dedicated to Brahms and played under Brahms’ baton. In contrast to many other 19th-century concertos that are dominated by flashy but meaningless shows of virtuosity, Brahms’ and Joachim’s concertos are characterized by a type of structural integrity and gravitas inspired by the piano and violin concertos of Beethoven, and it is this characteristic that has ensured the continued success of Brahms’ concerto.

—Heather Platt, Sursa Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts