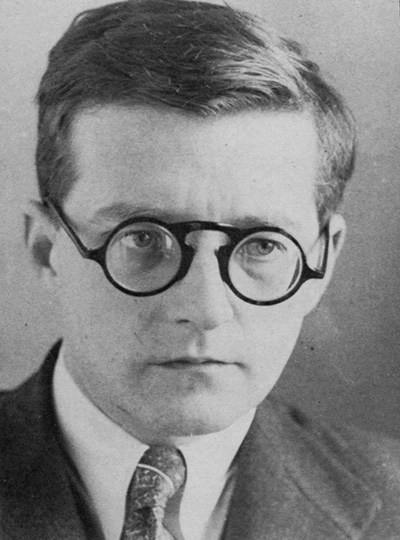

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: May 22, 1813, Leipzig, Germany

Died: February 13, 1883, Venice, Italy

Festive Overture, Op. 96

- Composed: 1954

- Premiere: November 6, 1954 at the Bolshoi Theatre

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 3 oboes, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals, snare drum, triangle, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: September 1971 in Eden Park, Erich Kunzel conducting. First Subscription Concert: November 1983, Jorge Mester conducting. Most Recent: (Pops) January 2018, John Morris Russell conducting; (CSO Subscription) March 1993, Jesús López Cobos conducting. Recording: 1988 Symphonic Spectacular, Erich Kunzel conducting.

- Duration: approx. 6 minutes

This delightful short work falls chronologically between two of Shostakovich’s most serious symphonies: the Tenth, which contains a diabolical scherzo reputed to be a “portrait of Stalin,” and the Eleventh, which commemorates the bloody events of the 1905 revolution. Shostakovich whipped it off, literally in one day, in response to a call from Vassili Nebolsin, a conductor at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, who urgently needed a festive piece for November 7, the anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917 . Lev Lebedinsky, a musicologist and close friend of the composer’s during the 1950s, told the story in an interview with British cellist and author Elizabeth Wilson. (See Wilson’s fascinating Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Princeton University Press, 1994).

“Shostakovich composed the Festive Overture before my very eyes,” recalled Lebedinsky, who happened to be in Shostakovich’s apartment when a desperate Nebolsin arrived to announce an emergency. Lebedinsky watched as the composer sat down to compose the overture. Shostakovich kept talking to his friend and making jokes even as he was composing. As soon as he finished a page, a courier came and took it away to be copied, in an almost exact replay of how Rossini had written his famous overture to La gazza ladra (“The Thieving Magpie”) in 1817.

This amazing effortlessness can be heard in the light and carefree tone of the music, yet the quality of the musical ideas and the craftsmanship with which they are presented never let us suppose that the composer had no time at all to plan or even think about the piece. What Shostakovich did here is as close to improvisation as a symphonic composer can ever come: the conception and the realization of the piece were virtually simultaneous.

Of course, Shostakovich had the classical sonata-form model to fall back on: after an introductory fanfare, he duly presents his two themes (the first consists mainly of rapid eighth-note passages, while the second has an expressive, singing character). The subsequent development, recapitulation and return of the opening fanfares as a concluding section were all part of the traditional framework that Shostakovich could well take for granted, like so many composers before him. But the freshness of the materials that fill in that framework, the brilliant orchestration and the effervescence of the whole piece are true signs of genius. They explain why the Festive Overture, originally written to help a colleague in a pinch, has entered the standard repertoire and held its place there for 70 years.

—Peter Laki