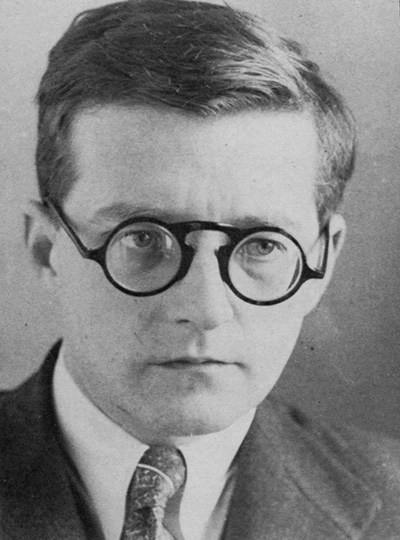

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: May 22, 1813, Leipzig, Germany

Died: February 13, 1883, Venice, Italy

Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 107

- Composed: 1956

- Premiere: October 4, 1959 at the Leningrad Conservatory with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting and Mstislav Rostropovich, cello

- Instrumentation: solo cello, 2 flutes (incl. piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (incl. contrabassoon), horn, timpani, celeste, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: April 1982, Erich Bergel conducting with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. Most Recent: November 2017, Louis Langrée conducting with cellist Truls Mørk.

- Duration: approx. 30 minutes

Shostakovich enjoyed a special friendship and artistic partnership with Mstislav Rostropovich for many years. The cellist was a teenager when he first met the composer, who was his senior by 21 years, in 1943. Enrolled at the Moscow Conservatory as a student of both cello and composition, Rostropovich took Shostakovich’s orchestration class. His admiration for his teacher knew no bounds, and after Shostakovich had heard the young man play, the admiration became mutual. During the 1950s, the two played Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata (1934) in concert tours all over Russia, and their friendship deepened. Throughout those years, Rostropovich was dreaming of a concerto Shostakovich might one day write for him. But the composer’s wife told him, “Slava, if you want Dmitri Dmitriyevich [the composer’s middle name] to write something for you, the only recipe I can give you is this—never ask him or talk to him about it.”

Rostropovich followed this advice, however reluctantly. And then one day in 1959, the concerto suddenly materialized. The ecstatic cellist committed the entire piece to memory in just four days, astounding the composer when the two got together at Shostakovich’s summer home on August 6, 1959. In her book of recollections, Elizabeth Wilson (a student of Rostropovich) reports the following conversation between them:

“Now just hang on a minute while I find a music stand,” Shostakovich said.

The cellist answered: “Dmitri Dmitriyevich, but I don’t need a stand.”

“What do you mean, you don’t need a stand, you don’t need one?”

“You know, I’ll play from memory.”

“Impossible, impossible...”

Rostropovich proceeded to play the work from memory with the pianist he had brought with him, to the utter delight of the composer and a small number of friends who had gathered in the music room. Afterward, they celebrated with a festive dinner. Everyone knew they had witnessed a historic moment.

The first public performance, two months later, was enthusiastically received and was soon followed by an international triumph, establishing the work as the most significant addition to the cello concerto literature in a long time. Shostakovich, inspired by an exceptional instrumentalist with whom he had bonded deeply, had written a work that combined immediacy of expression with formal perfection, and Romantic passion with Classical balance—a fusion of qualities we don’t find very often in the music of the 1950s. Nor had music ever communicated with an audience more directly or more sincerely.

Once you have heard the concerto’s opening motif, played by the cello, you are unlikely to ever forget this four-note theme. (It is immediately recognizable when quoted in Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet of 1960.) Varied, developed and taken into successively higher registers of the solo instrument, this little motif dominates the entire movement—and more. An insistent second theme appears a little later, and the music gradually gains in excitement and in technical virtuosity. The solo cello plays almost without intermission, although it is joined by the clarinet and especially by the horn as “assistant” soloists. The end of the movement returns to the opening theme in its original low register.

The remaining three movements are played without pause. First, we hear a slow movement (actually, the tempo is moderato), featuring—after a dreamy introduction—a very simple, folk-like melody. The introductory material is heard again, followed by a more passionate new idea, leading to a climax and a return of the folk-like theme in high-pitched cello harmonics.

The third movement is a lengthy, unaccompanied cadenza, beginning slowly and becoming faster and faster. Russian critic Lev Ginzburg aptly called it a “monologue-recitative.” The movement, although exceedingly hard to perform, is not a mere display of technical difficulties but, in Ginzburg’s words, a piece of “deep meditation, reaching philosophical heights.” It leads directly into the exuberant finale, which opens with a dance tune—not an ordinary dance tune, though, but one spiced with many chromatic half-steps that give it a striking, sarcastic overtone. The theme is introduced by the oboe and the clarinet, giving the soloist a respite after the exhausting cadenza. The solo cello soon re-enters, however, repeating the dance-tune, followed by a second dance. The latter unexpectedly morphs into the memorable opening theme from the first movement, providing the material for the energetic conclusion of the concerto.

As a kind of private joke, Shostakovich concealed in this movement some distorted fragments of a folksong from Georgia in the Caucasus, Stalin’s birthplace; the song, “Suliko,” had reportedly been the late dictator’s personal favorite. But even Rostropovich confessed: “I doubt if I would have detected this quote if Dmitri Dmitriyevich hadn’t pointed it out to me.”

—Peter Laki