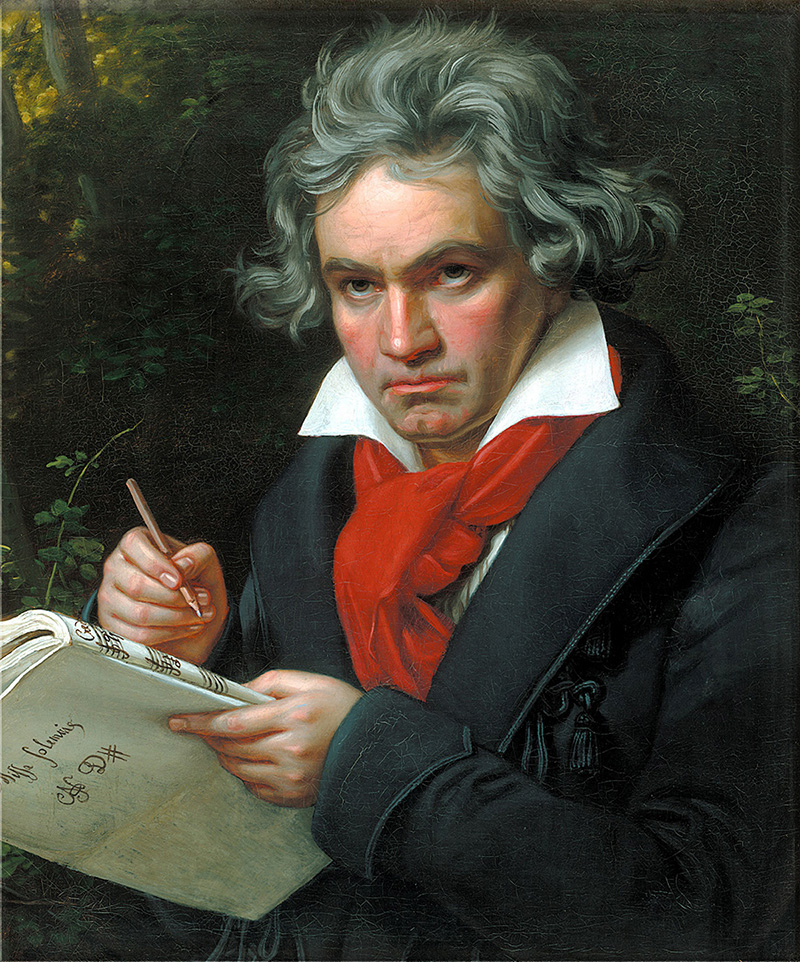

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Leonore Overture No. 2 in C Major, Op. 72a

- Composed: 1805

- Premiere: November 20, 1805 in Vienna, conducted by Ignaz von Seyfried under the composer’s supervision

- Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings

- CSO notable performances: First: December 1916, Ernst Kunwald conducting. Most Recent: November 2015, Louis Langrée conducting.

- Duration: approx. 13 minutes

The decade (1804-1814) that Beethoven devoted to his only opera, Fidelio, was an unprecedented amount of time to spend perfecting such a work during the early 19th century. Given the same 10 years, Rossini dispensed 31 (!) operas between 1810 and 1820, and Donizetti cranked out 35 (!!) specimens of the genre from 1827 to 1837. Even Mozart launched seven operas during his decade in Vienna. For Beethoven, however, Fidelio was more than just a mere theatrical diversion—it was his philosophy set to music. This story of the triumph of justice over tyranny, of love over inhumanity was a document of his faith. To present such grandiose beliefs in a work that would not fully serve them was unthinkable, and so Beethoven hammered and rewrote and changed until he was satisfied. In his book The Interior Beethoven, Irving Kolodin wrote, “As tended to be the life-long case with Beethoven, the overriding consideration remained: achievement of the objective. How long it might take or how much effort might be required was not merely incidental—such consideration was all but non-existent.”

The most visible remnants of Beethoven’s extensive revisions are the quartet of overtures he composed for Fidelio, the only instance in the history of music in which a composer generated so many curtain-raisers for a single opera. The first version of the opera, written between January 1804 and early autumn 1805, was initially titled Leonore after the heroine, who courageously rescues her husband from his wrongful incarceration. For that production, Beethoven wrote the Overture in C major now known as the Leonore No. 1, incorporating themes from the opera. The composer’s friend and early biographer Anton Schindler recorded that Beethoven rejected this first attempt after hearing it privately performed at Prince Lichnowsky’s palace before the premiere. (Another theory, supported by recent detailed examination of the paper on which the sketches for the piece were made, holds that this work was written in 1806–07 for a projected performance of the opera in Prague that never took place, thus making Leonore No. 1 the third of the Fidelio overtures.) He composed a second C major overture, Leonore No. 2, and this piece was used at the first performance, on November 20, 1805. (The management of Vienna’s Theatre an der Wien, site of the premiere, insisted on changing the opera’s name from Leonore to Fidelio to avoid confusion with Ferdinando Paër’s Leonore.) The opera foundered. Not only was the audience (largely populated by French officers of Napoleon’s army, which had invaded Vienna exactly one week earlier) unsympathetic, but there were also problems in Fidelio’s dramatic structure. Beethoven was encouraged by his aristocratic supporters to rework the opera and present it again. This second version, for which the magnificent Leonore Overture No. 3 was written, was presented in Vienna on March 29, 1806, but met with only slightly more acclaim than its forerunner.

In 1814, some members of the Court Theater approached Beethoven, by then Europe’s most famous composer, about reviving Fidelio. The idealistic subject of the opera had never been far from his thoughts, and he agreed to the project. The libretto was revised yet again, and Beethoven rewrote all the numbers in the opera and changed their order to enhance the work’s dramatic impact. The new Fidelio Overture, the fourth he composed for his opera, was among the revisions. Beethoven realized that the earlier overtures, especially the Leonore No. 3, simply overwhelmed what followed (“As a curtain raiser, it almost made the raising of the curtain superfluous,” judged Irving Kolodin), and, from a technical viewpoint, were in the wrong tonality to match the revised beginning of the opera. The compact Fidelio Overture, in E major, is now always heard to open the opera.

Although they are similar in scale, thematic material, instrumentation and expressive intent, the Leonore Overture No. 2 has long been overshadowed by the Leonore No. 3, one of Beethoven’s best-known and most powerful utterances. Both distill the essential dramatic progression of the opera into purely musical terms: the triumph of good over evil; the movement from darkness to light, from subjugation to freedom. Both use Florestan’s Act II aria as the material for a portentous slow introduction, and both create much of their musical substance from elaborations of the same arch-shaped main theme. Both preview the joyous climax of the opera to follow with the trumpet call that signals the overthrow of evil and with a jubilant coda. They differ, however, in the proportions of their structures: the Leonore No. 2 has a longer introduction and plunges directly into the coda after its trumpet call rather than recapitulating its themes to create a full sonata form, as does the Leonore No. 3. There is also in the Leonore No. 3 a concentrated, driving, explosive force for which, in retrospect, Beethoven seems to have used the Leonore No. 2 as a testing ground. Even so, the Leonore No. 2 is an important document of Beethoven’s genius, evidence of his endless quest to perfect his art, and a stirring musical essay in its own right. “There can be little doubt that the preference for No. 3 is justified,” wrote the eminent musicologist Donald N. Ferguson, “but the choice, when once No. 2 has become familiar, is not wholly easy to make.”

—Dr. Richard E. Rodda