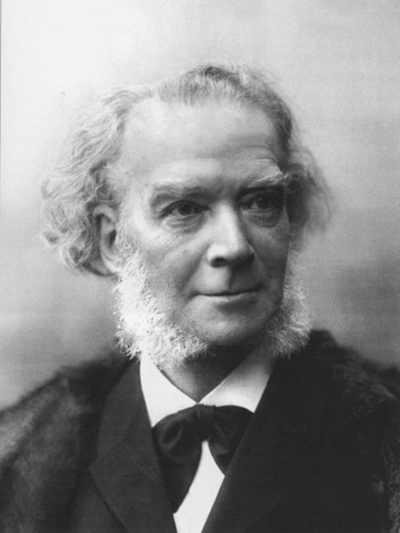

Carl Reinecke

Born: June 23, 1824, Altona, Germany

Died: March 10, 1910, Leipzig, Germany

Trio in B-flat Major for Clarinet, Horn and Piano, Op. 274

- Composed: 1905

- Premiere: 1906

- Duration: approx. 28 minutes

“I am quite aware that I no longer play a role in the present,” observed composer Carl Reinecke in his final years, with no hint of sentimentality whatsoever. For a full 35 seasons he had led both the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Conservatory. He had not only followed in the footsteps of Felix Mendelssohn, the orchestra’s first music director and the conservatory’s founder, but had surpassed Mendelssohn’s tenure as measured both in accomplishments and in years. Reinecke had worked hard to distinguish himself from his predecessor in all three domains: as conductor, composer and pedagogue. He had successfully challenged the inherent conservativism of the Leipzig public and of audiences around the world for several decades. As he wrote in his autobiography, Erlebnisse und Bekenntnisse (“Experiences and Confessions”), “Heaven has granted me the privilege of advanced age, and so I have enjoyed the undeserved good fortune of celebrating many beautiful anniversaries—first a 25th anniversary as conductor of the Gewandhaus concerts, then on November 23, 1893, the anniversary on which I had performed for the first time as a pianist in the same institute 50 years previous, and then my 70th birthday, and on June 23, 1904, my 80th birthday.”

Reinecke’s later works rank among his most lyrical and poetic. As a young composer, he had been criticized by Schumann for lacking an original voice and by Mendelssohn for lacking interest. In his 70s, though, he had soloists of the Gewandhaus Orchestra begging him for more compositions. It was for them that he wrote many of his best-known chamber works: his sextet for winds and piano, his clarinet trios and his “Undine” sonata for flute—works that perfectly capture the autumnal beauty of Reinecke’s distinctive voice.

The maestro had fully withdrawn from the public eye when the Gewandhaus extended an invitation to perform once again on the stage that had been his home for so many years. Several notable works followed, for esoteric instrument combinations: Op. 188 for oboe, horn and piano; Op. 264 for viola, clarinet and piano, and Op. 274 for clarinet, horn and piano. Reinecke composed the Op. 274 trio in 1905, five years before his death, and it was premiered the following year. In Op. 274 we hear the work of a superior artisan writing in the spirit and harmonic language of the late Romantic period, just as it was trickling to an end.

Indeed, the first movement, Allegro, is in a conventional sonata form that owes much to Brahms and Schumann. It opens with a dark fanfare that passes to the clarinet before blossoming into a proper first theme. A duet in E-flat between the two winds follows, laying out the second theme that then develops and blends with the closing theme. The piano crescendos to a long climax and offers a clear cadence in B-flat major only in the final moments.

Reinecke titled his second movement Ein Märchen, a German fairytale; this is a moniker that Schumann also employed, to connect his works to the Romantic literary preoccupation with the supernatural. Crafted as an Andante in G major, there is only a touch of the otherworldly in this movement; Reinecke’s picture is often more placid than macabre.

Reinecke chose a scherzo for his third movement, complete with two contrasting trios. The composer provides no return to the opening scherzo to separate the trios; only an ascending chromatic keyboard flourish and the accompanying modulation to D major mark the transition from one to the next. The instrumental writing here is noteworthy in the technical demands placed upon the horn.

The work concludes with another Allegro. The clarinet introduces the main theme, and subsequent sections give each player a chance to shine. The opening Eastern European dance is soon subverted by a heavier quality that quickly yields to the hallmarks of Reinecke’s compositional language: hemiolas, imitation, rich chromaticism, and constant dialogue among the three instruments.

In his final years, Reinecke was fully aware that his musical voice was that of an older tradition, one that set him at odds with the aesthetic changes of the turn of the century. Of the success of his late chamber works he observed, “The musical world will leave them quite unnoticed because I have not progressed with the times…[but I] have always remained true to my convictions.”

—Dr. Scot Buzza