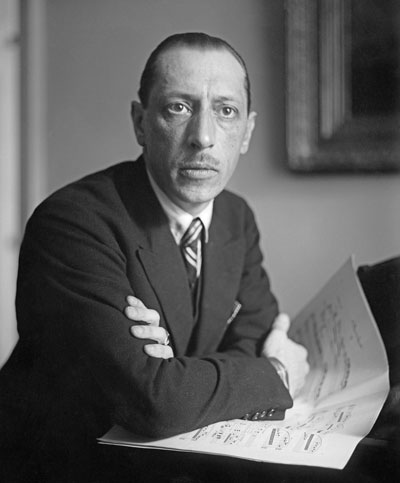

Igor Stravinsky

- Born: June 17, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia

- Died: April 6, 1971, New York

The Firebird Suite (1919)

- Composed: November 1909-May 18, 1910

- Premiere: (complete ballet) June 25, 1910, Paris Opéra, Ballets Russes

- Duration: approx. 13 minutes

Serge Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes had an enormously successful debut performance in Paris in the summer of 1909. Diaghilev and his chief choreographer, Michel Fokine, began to make plans for future performances in the city that most appreciated their talents. Fokine felt it necessary to add to their repertory a ballet on a Russian folk subject. After reading several folktales, he decided that the legend of the Firebird could be adapted to the dance. He worked out a scenario in which Katschei the Immortal, one of the most fearsome ogres in Russian folklore, is defeated by the Firebird.

Then came the crucial question of who was to be the composer. Rimsky-Korsakov would have been the logical choice, since he had written an opera on the subject of the Firebird a few years earlier, but he had died unexpectedly in 1908. Nicholas Tcherepnin and Sergei Vassilenko were considered, but Diaghilev decided to commission Anatol Liadov, who had written a number of orchestral works based on fairy tales. Liadov proved to be a slow worker, however, and reportedly was just buying the music paper at the time Diaghilev had hoped to receive a finished score.

Diaghilev and Fokine had recently heard a concert that included two works that greatly impressed them: Scherzo fantastique and Fireworks by the relatively unknown young composer Igor Stravinsky. So the commission went to Stravinsky. The composer was flattered to receive what turned out to be the first of several commissions from the great impresario.

Clearly in the popular tradition of Rimsky-Korsakov, who had been Stravinsky’s teacher, Firebird was nonetheless boldly original and extremely colorful. The composer was not completely comfortable writing descriptive music, but he knew the importance of the commission and produced exactly what Diaghilev needed. The ballet, while not typical of Stravinsky, became (and remains) his best known work. An amusing story shows how popular the work is: a stranger once came up to the composer and asked if he were indeed the famous composer, Mr. Fireberg!

As soon as the score was ready in piano reduction, the company began to rehearse. Many people heard Stravinsky play the exhilarating new music at the keyboard. A typical reaction was that of French critic R. Brussel, who had been invited by Diaghilev to hear the ballet score:

The composer, young, slim, and uncommunicative, with vague meditative eyes and lips set firm in an energetic-looking face, was at the piano. But the moment he began to play, the modest and dimly lit dwelling glowed with a dazzling radiance. By the end of the first scene, I was conquered; by the last, I was lost in admiration.

Ballerina Anna Pavlova was originally cast in the title role, but she found the music incomprehensible. She was replaced by Tamara Karsavina, whose knowledge of music was only rudimentary. She had to rely on the composer for help:

Often he came to the theater before a rehearsal began in order to play for me, over and over again, some particularly difficult passage. I felt grateful, not only for the help he gave me but also for the manner in which he gave it. For there was no impatience in him with my slow understanding, no condescension of a master of his craft towards the slender equipment of my musical education. It was interesting to watch him at the piano. His body seemed to vibrate with his own rhythm. Punctuating staccatos with his head, he made the pattern of his music forcibly clear to me, more so than the counting of bars would have done.

Finally the company was ready for Paris. There were rehearsals with the orchestra, and at last the performance. It was the first great triumph for Stravinsky, and it solidified the reputation of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev went on to commission two more major ballets from Stravinsky, Petrouchka and Rite of Spring, plus several smaller works. He also sought out other leading or promising composers, including Debussy, Ravel, Falla and Prokofiev.

Three times Stravinsky returned to Firebird to extract the concert suites that today are heard far more often than the complete ballet. The composer’s reason was partly artistic and partly practical. Once he began to have a career as a conductor, Stravinsky wanted to be able to perform a suitable set of excerpts from his most popular theater work. Furthermore, the ballet had been composed in Czarist Russia and therefore was not protected under international copyright agreements. The same is true, incidentally, of his other two early ballets, Petrouchka and The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky was thus robbed of substantial income. To try to remedy this problem, he copyrighted the later Firebird Suites.

The first suite (sometimes called Symphonic Suite) was extracted in 1911, when the piece was still new. It uses the same large (“wastefully large,” Stravinsky later called it) orchestra. In fact, it was printed from the same plates as the complete ballet, with appropriate omissions and a few small changes. This suite ends with the exciting “Infernal Dance.”

In 1919, after Stravinsky had left Russia and was living in Morges, Switzerland, he made a different Firebird Suite (sometimes called the Concert Suite) for conductor Ernest Ansermet. The orchestra is of normal rather than outlandish size. This suite omits two movements that appear in the 1911 version, but it adds at the end the “Berceuse” and “Finale.”

When the 1919 suite was published, its score was full of mistakes. Many of these errors found their way into the third version (sometimes known as the Ballet Suite), which Stravinsky derived in 1945 from the second version and from the complete ballet. Although the 1919 suite has always been the best known of the three, only in 1985 did it become available in a corrected edition.

Stravinsky faced a compositional challenge in The Firebird. How could he musically differentiate the natural (Ivan, the Princess, the finale’s hymn of rejoicing) from the magical (the Firebird, Katschei)? His idea, derived from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Golden Cockerel, was clever. The natural characters and scenes were composed in a diatonic style, while the supernatural were interpreted with chromatic music.

The orchestration in Firebird is spectacular. Although he was still in his 20s, Stravinsky was already a master of scoring. The famous passage of natural harmonic string glissandos, at the end of the introduction, is one of the most beautiful sonorities in the piece. Some of the other well-known effects, such as trombone and French horn glissandos, were added only when Stravinsky made the Firebird Suite of 1919. The colorful orchestral and rhythmic drive of the “Infernal Dance” foreshadow the brutally primitivistic world of The Rite of Spring, composed three years later.

—Jonathan D. Kramer